Reading time 30 minutes

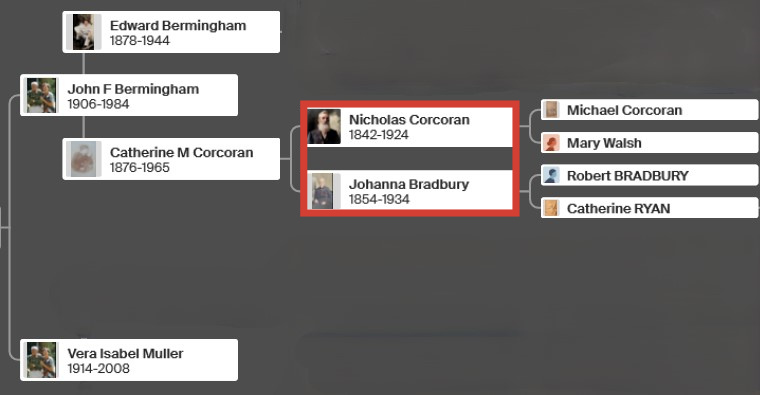

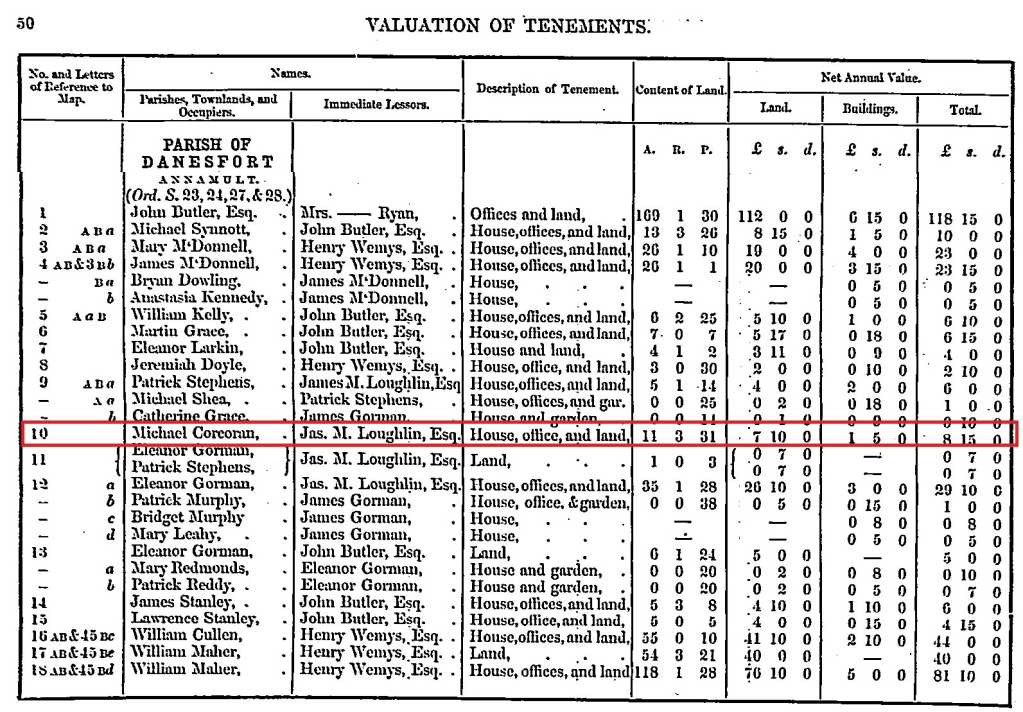

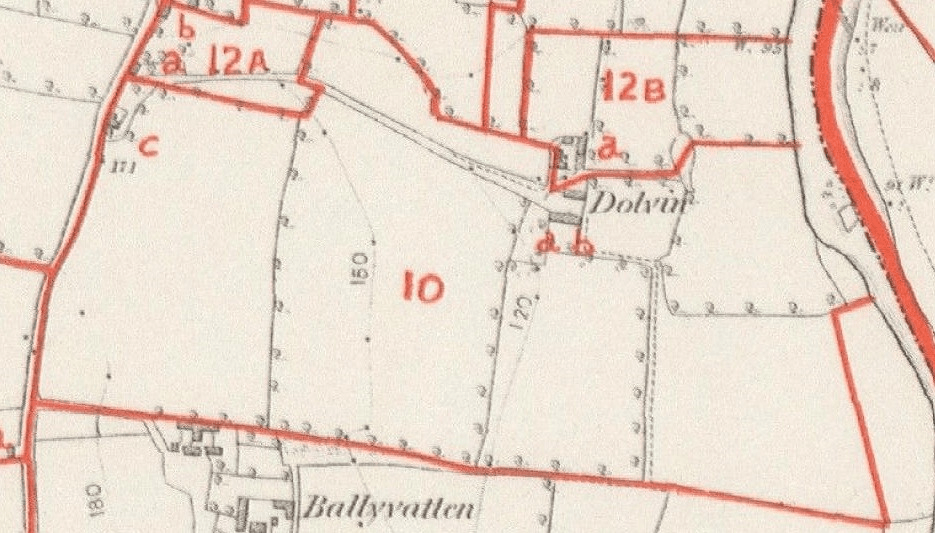

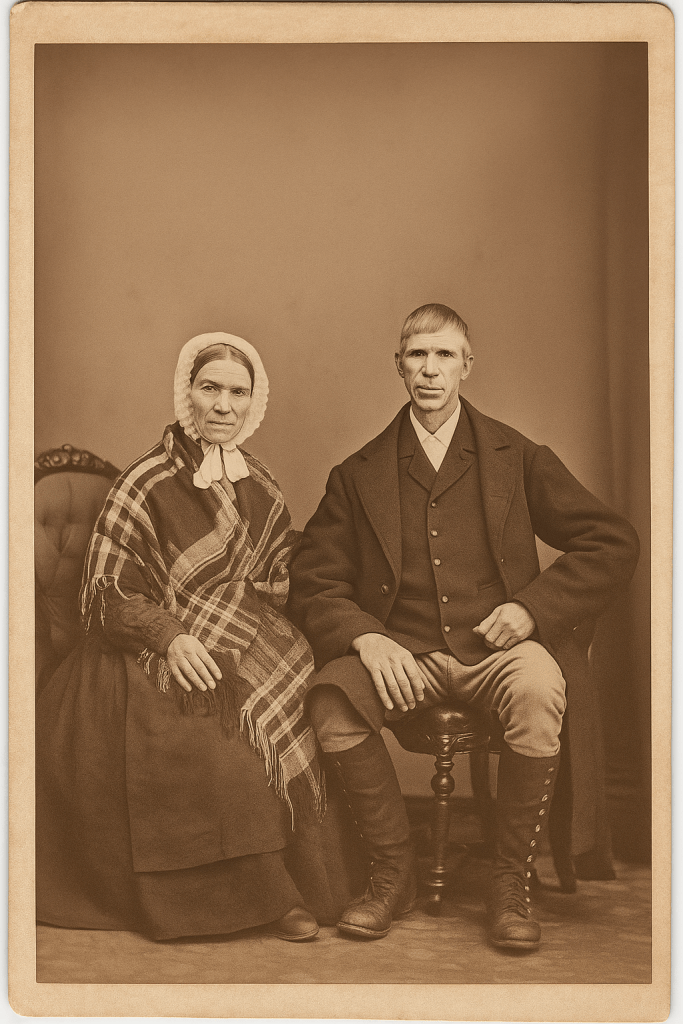

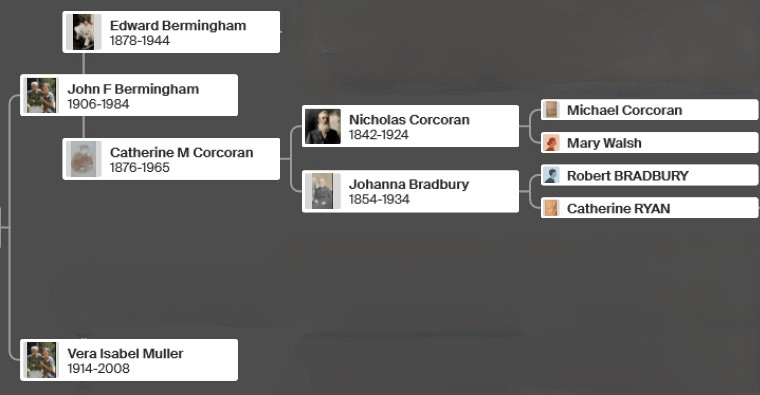

When my great-grandfather, Nicholas Corcoran, was born on January 12, 1842, in Danesfort, Kilkenny, Ireland, his father, Michael, was 32, and his mother, Mary (née Walsh), was 33. He was the first of eight children:

- Nicholas (1842–1924)

- Ellen (1843–1876)

- Matthew (1844–1899)

- Patrick (1847– )

- Bridget (1849–1940)

- James (1850–1921)

- Margaret (1854–1924)

- Kate (1866–1928)

Michael and Mary Corcoran were tenant farmers. Until about 1900, approximately 97% of Irish land was owned by landlords and rented out to tenant farmers, who were required to pay rent to landlords as well as taxes to the Anglican-affiliated Church of Ireland and the ruling UK government. Most of the population had no access to land ownership. The exploitation of tenant farmers led to widespread emigration to the United States, Canada, South Africa, and Australia.

Nicholas would have been a young child growing up during the Great Famine in Ireland (1845–1849). As an Irish Catholic, he would have faced significant prejudice and discrimination under British rule. This likely intensified his desire—along with that of many others—to escape the persecution that the Irish had endured for centuries.

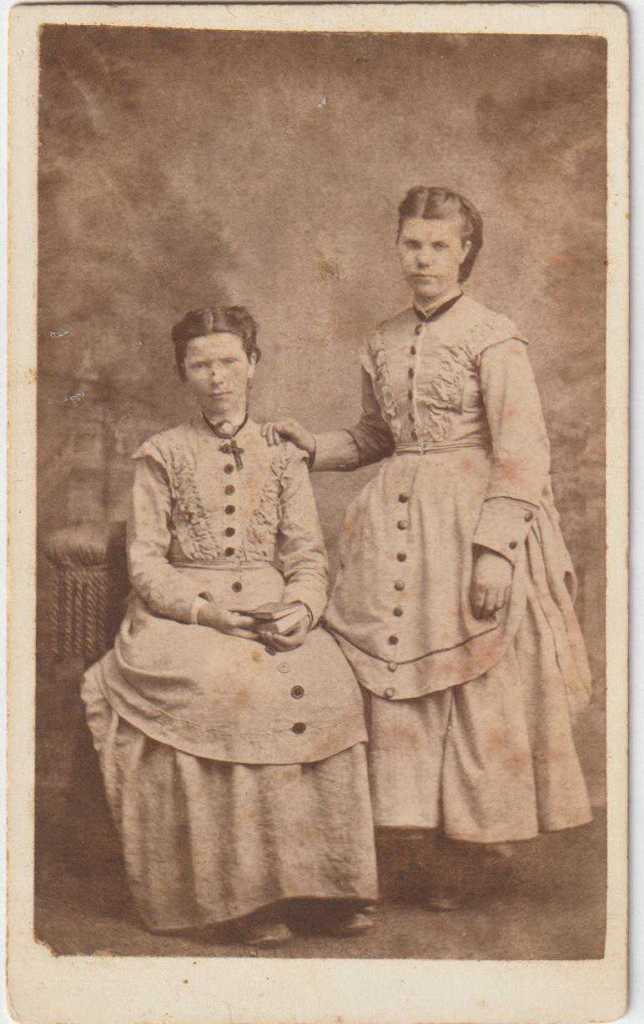

His sisters Bridget and Ellen also came to Australia, with a brother Patrick heading to America, where he became a policeman.

While researching my family’s history, I came to realize how much denial still exists regarding British persecution of the Irish, even in modern times. The Church of England, the British royal family, governments, and private institutions have all attempted to rewrite history, presenting their own version of events to downplay the harsh realities of British actions. This period of immense suffering in Irish history has, in many ways, left lasting scars that continue to the present day.

In 1649, during his invasion of Ireland, Oliver Cromwell carried out ethnic cleansing on a massive scale, with estimates of over 600,000 deaths. At the time, Ireland’s total population was approximately 1.5 million, meaning the country lost over one-third of its people to genocide. To make matters worse, famine and plague claimed even more lives.

In the mid-1800s, approximately one million people perished during the Great Irish Famine. Following this tragedy, two million more emigrated to the United States, Canada, Australia, and other parts of the world in search of a better life. Even today, I believe that many non-Irish Australians remain largely unaware of the extent of the mistreatment the Irish endured in their homeland. The scale of suffering over the centuries of Irish history is comparable to the Nazi Holocaust in its magnitude over the centuries of Irish history.

The British had prior form for this type of brutality, in other parts of the world with their colonization of countries across America, Africa and Asia. India was another country that the British raped & pillaged. The ruthless treatment that the British East India Company (under the auspices of the ruling British Government) carried out on the Indian population is one of the most shameful chapters of world history.

Looking back into the archives & records of the world, it’s plain to see many countries suffered at the hands of the ruling classes of the time. Ireland suffered terribly for centuries at the hands of the British government. The protestant, Church of England’s British Government, never really made any secret of the fact, that their intentions at the time of the potato famine, were to lower the Catholic population of Ireland by letting the Famine take its natural course of people starving to death. There were alternate food supplies available in Ireland, at the time. The Irish Catholic population just wasn’t given access to any of it.

While researching these unfortunate times in Ireland’s history, I often considered, from a modern perspective, what circumstances would be severe enough to make someone leave their home, family, and friends to travel to the other side of the world with almost nothing—relying only on the uncertain promises of a new country that may or may not welcome them upon arrival.

It was, in many ways, the equivalent of traveling to another planet today—setting out with little knowledge or confidence that you would even reach your destination safely. Perhaps the answer to that question lies in sheer desperation and the unwavering faith that life had to be far better than the misery left behind.

That being said, there seem to be no real attempts to make amends for the past atrocities committed against the Irish. The British government, the ruling classes, and the royal family were also guilty of terrible persecution against their own citizens.

I can completely understand why Northern Ireland’s Catholic population continues to feel uneasy about remaining part of the UK. Centuries of persecution do not simply fade away. Even today, the UK government refuses to grant Northern Ireland independence, despite Sinn Féin holding the most seats in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

I recognize that we cannot dwell endlessly on the wrongdoings of past generations. Governments of bygone eras ruled with an iron fist—whether in the UK, Germany, or colonial Australia. We have seen how history was shaped in Australia by the ruling classes of the time, and only now is the true history of the mistreatment of First Nations people becoming more widely acknowledged.

Even so, far too many Australians either refuse to believe that these atrocities took place or are too ignorant to accept the truth. The racist beliefs of past generations still persist in modern-day Australia.

Sidenote observation – As a descendant of Irish ancestors, I do not hold any deep-seated animosity toward the British people today. However, I would be more than happy to see Australia sever ties with the British royal family as our head of state. I view them as an antiquated, pompous institution that has long outlived its relevance.

Australia, as a nation, is long overdue for maturity—we must finally grow up and become a republic. It is time to shake off the shackles of this outdated monarchy, which contributes nothing to our trade, cultural identity, or national security.

………………………………

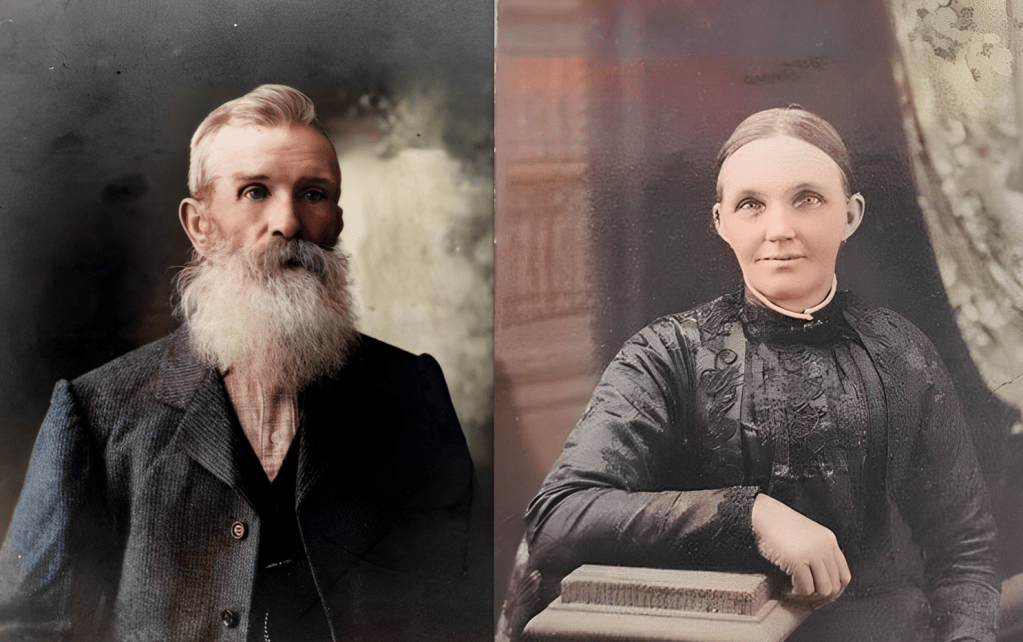

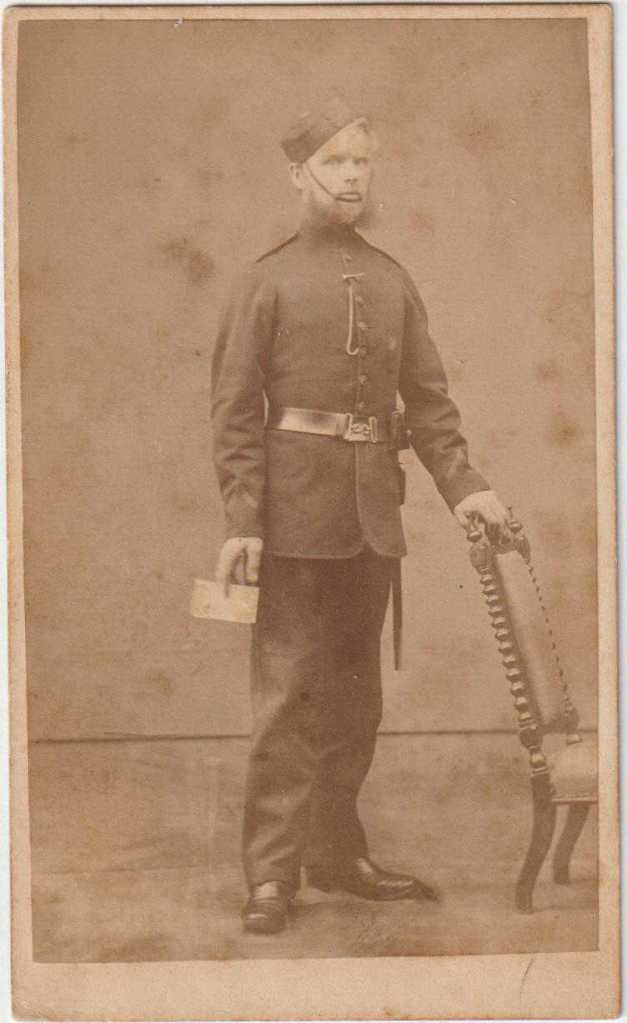

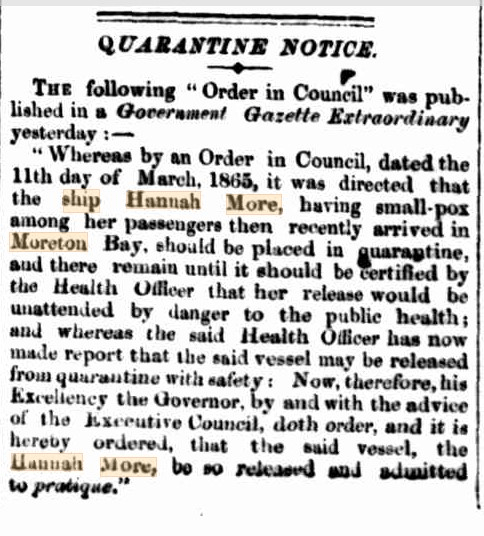

Nicholas Corcoran emigrated from Ireland on the Hannemore out of Liverpool 12th November 1864, with 335 fellow government sponsored immigrants on board.The ship arrived in Moreton Bay on the 9th March 1865. Coming from Kilkenny, he would have been fairly knowledgeable about horse breeding, as that part of Ireland had always been, and still is a major equine breeding area.

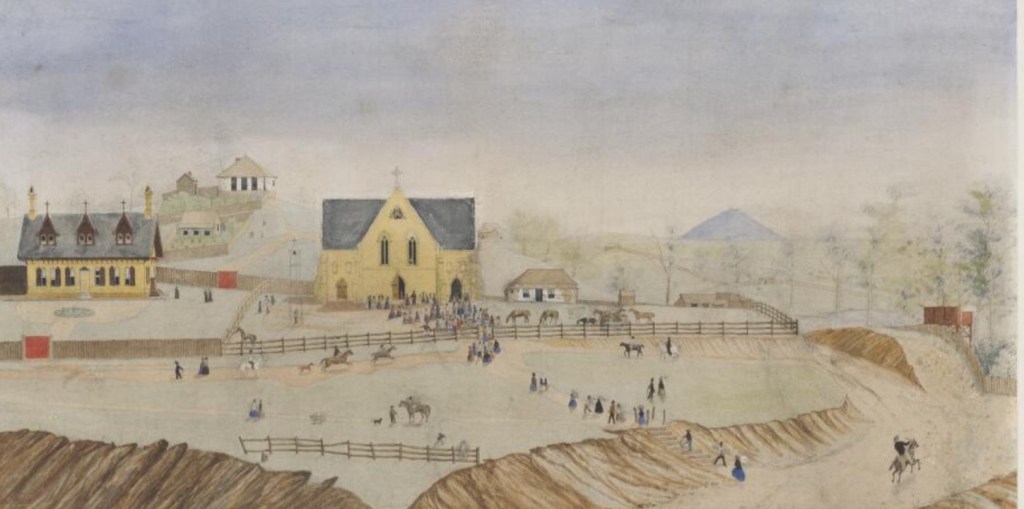

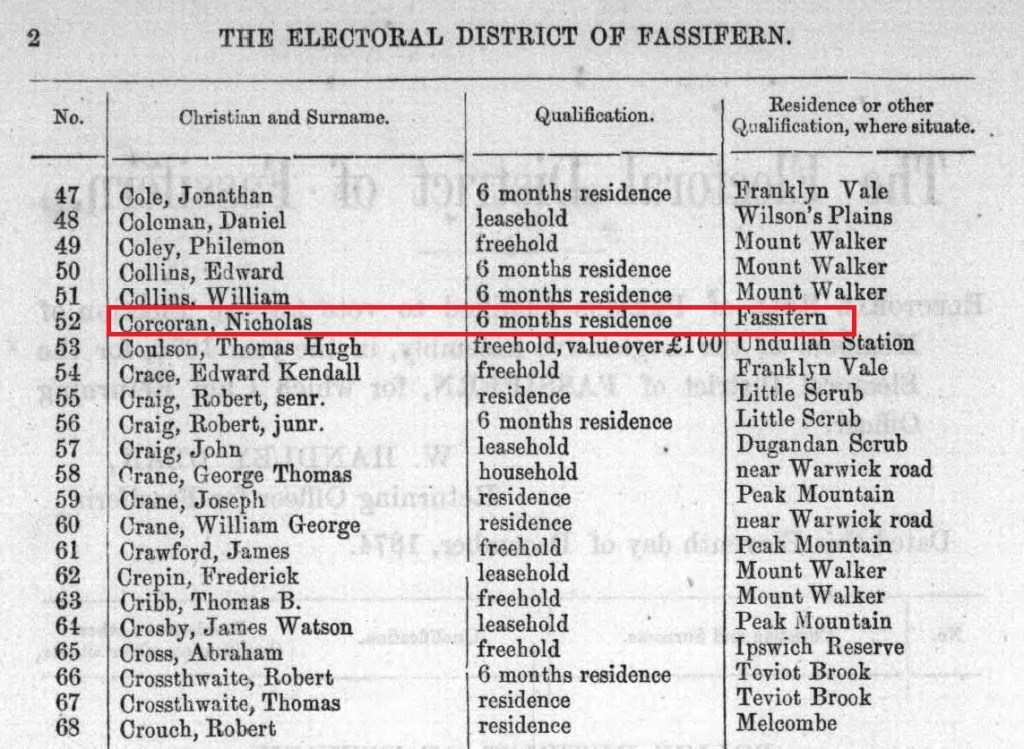

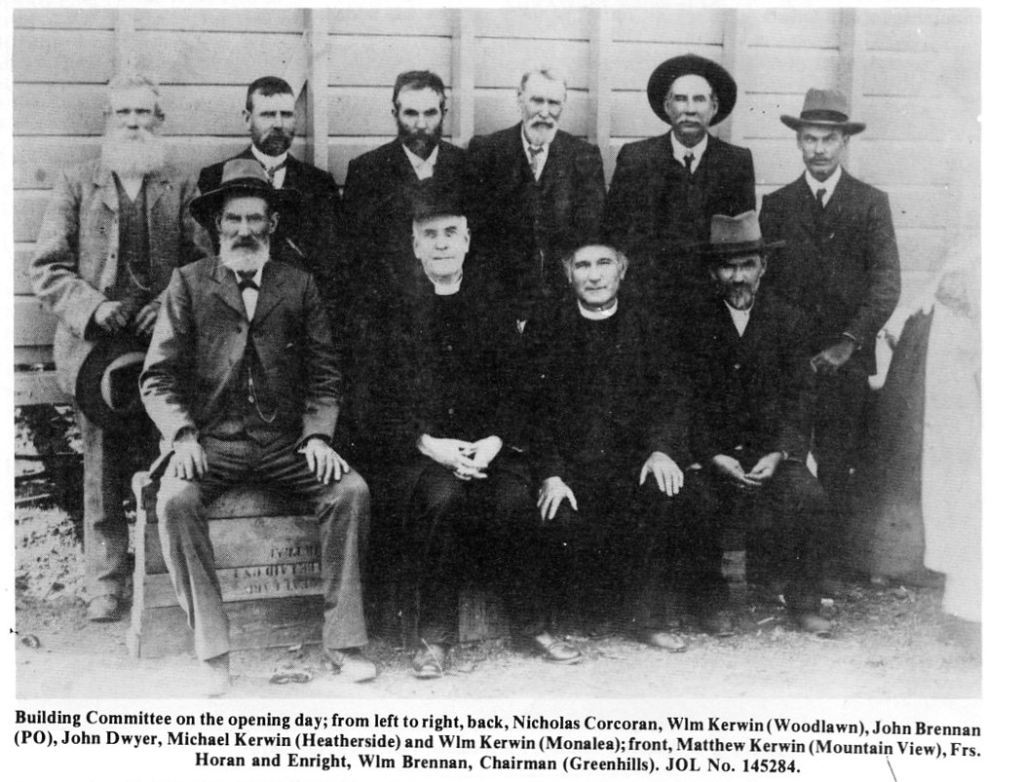

After arriving in Brisbane from Ireland, twenty-three-year-old Nicholas pursued various occupations across the Ipswich, West Moreton, and Darling Downs regions. From 1869 to 1885, he worked for the Wienholt Brothers, who held significant land across Queensland and were pioneers in cattle grazing and horse breeding during the early settlement and farming period of Southern Queensland.

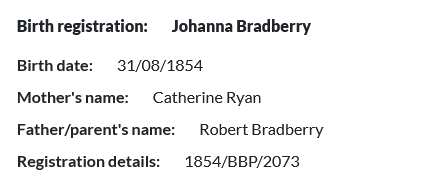

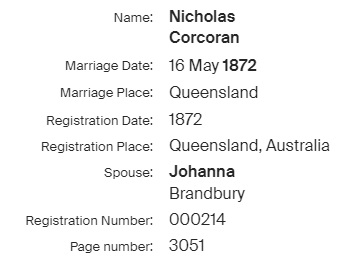

When my Great Grandmother Johanna Bradbury was born in Laidley, Queensland on 31 August 1854, her father Robert Bradbury was 42, and her mother Catherine (Ryan) was 23. She was the first of three children, with a brother, Robert (Jnr) & a sister, Mary Ann. The Bradbury family lived around the Ipswich and Lockyer Valley districts. They moved on a regular basis, due to Robert’s work as a shepherd/farm labourer.

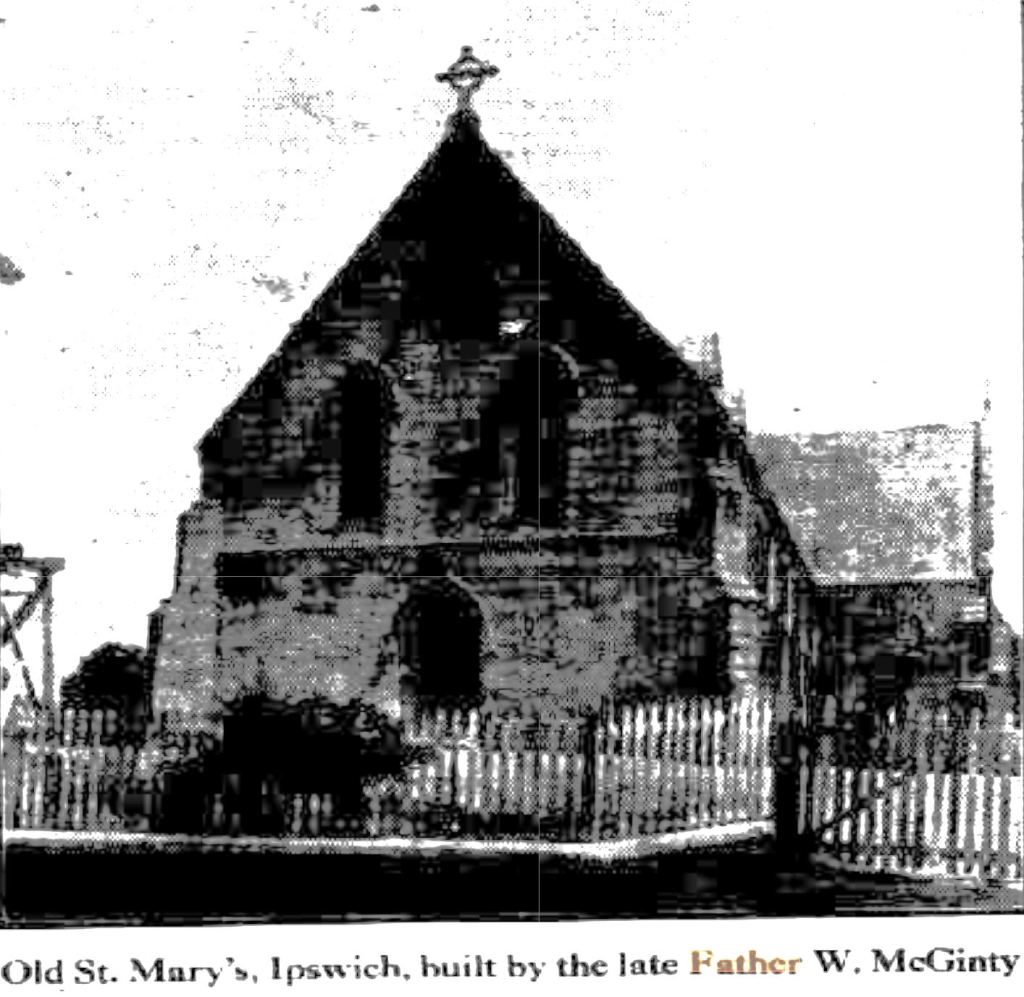

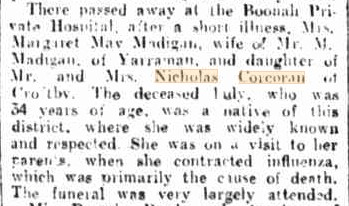

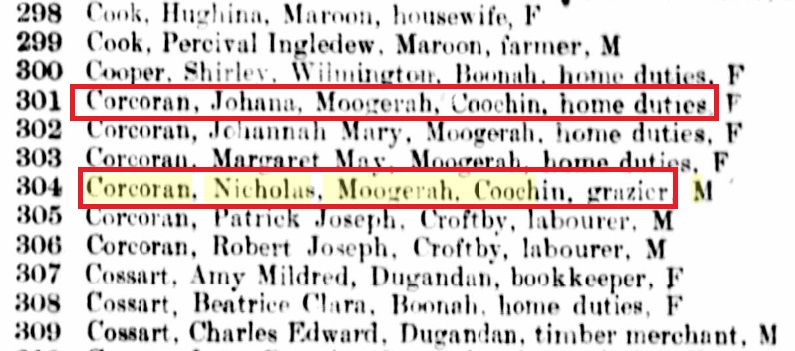

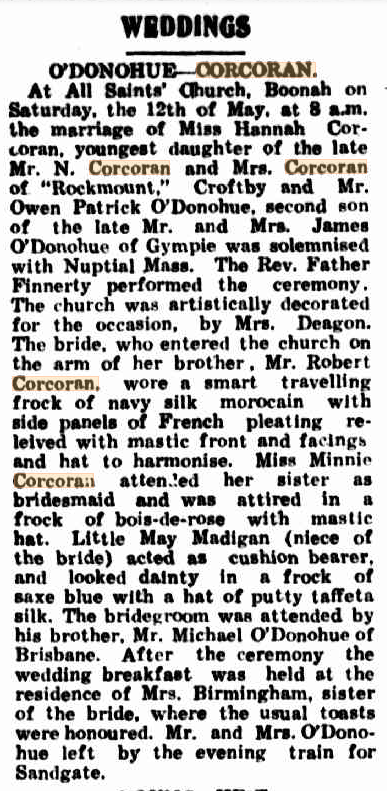

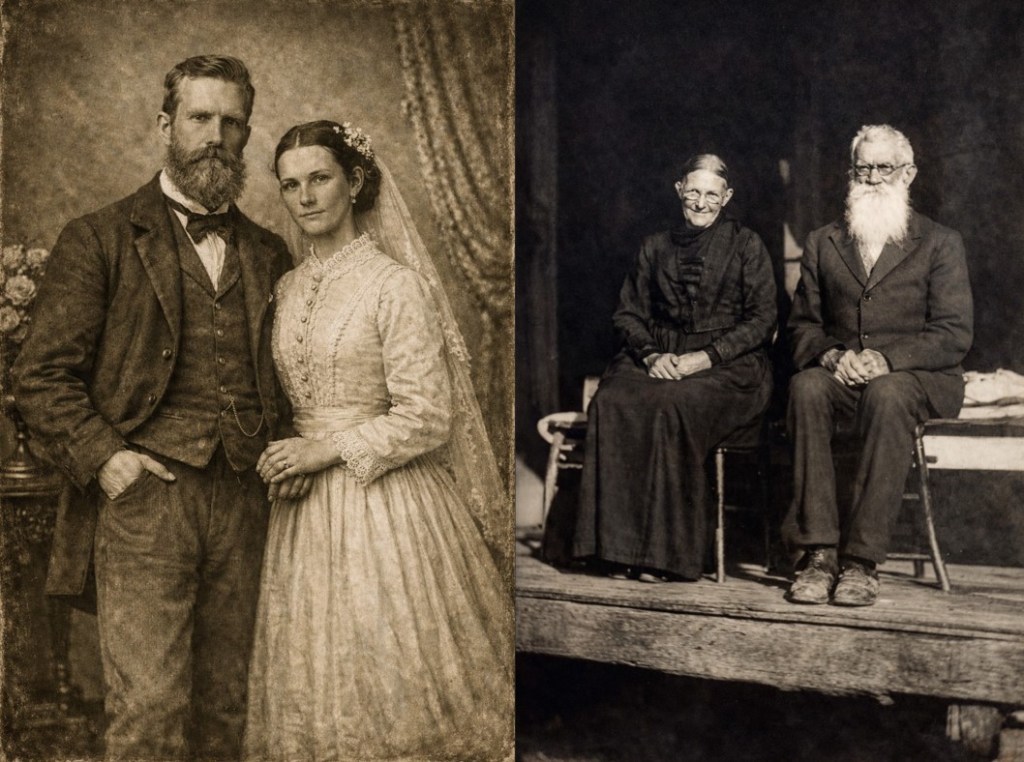

Nicholas Corcoran married Johanna Bradbury at St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Ipswich, on 16th May 1872, when he was 30 years old. They had 11 children in 19 years – Michael Patrick born 11-12-1873, Catherine Mary 20-11-1876, Mary(died at birth), Robert 14-2-1879, Ellen 15-1-1881, Johanna 14-2-1883 (died 1885), Mary Ann 8-6-1884, Nicholas James 16-7-1886, Margaret May 15-5-1889, Patrick Joseph 29-3-1891 & Johanna Mary 21-3-1893. A nephew, Charles Patrick Gilday, son of Nicholas’ sister Ellen, & her husband Cornelius Gilday, was also raised by the family. Charles’s parents both died when he was young.

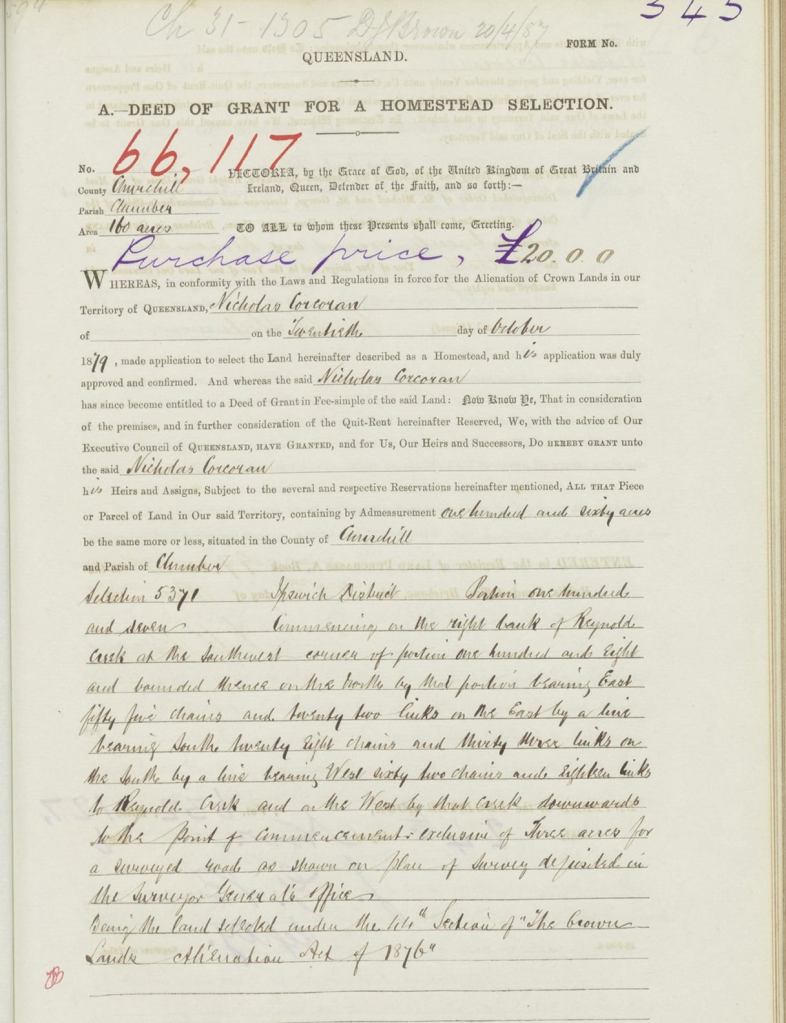

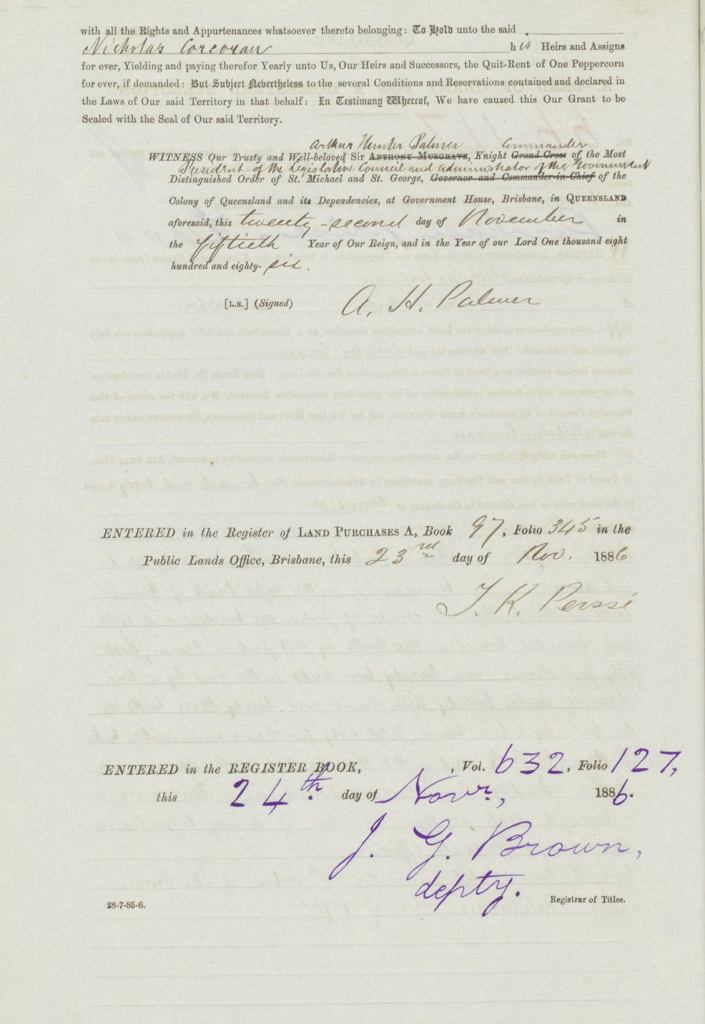

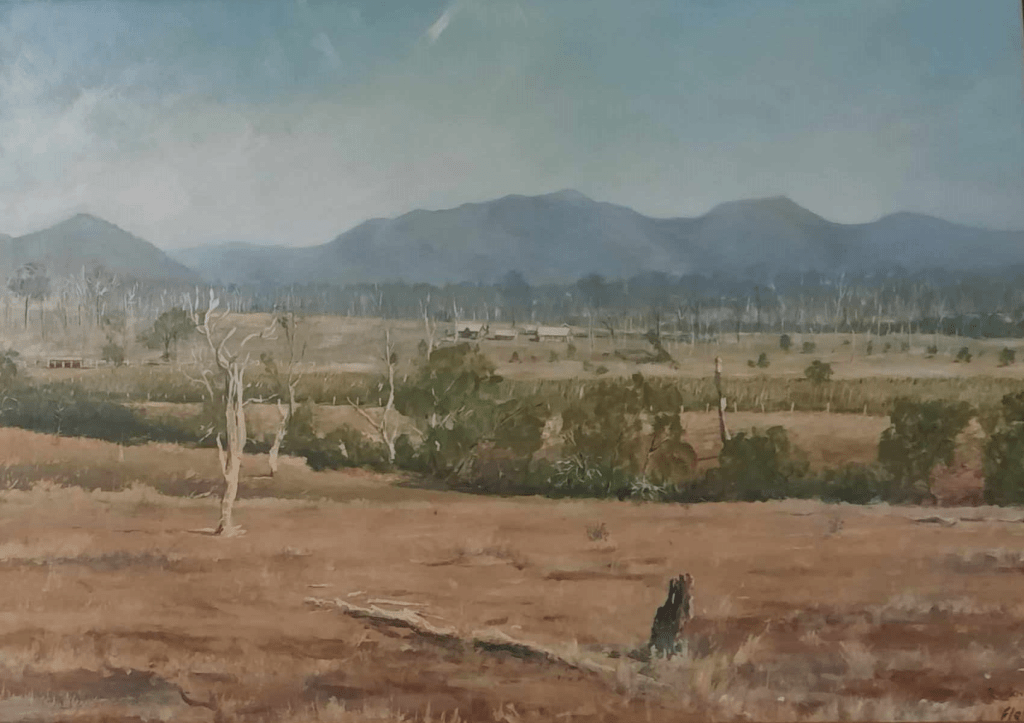

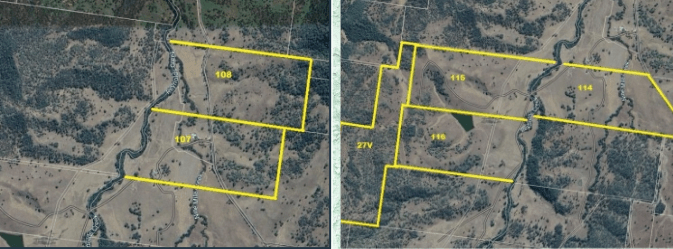

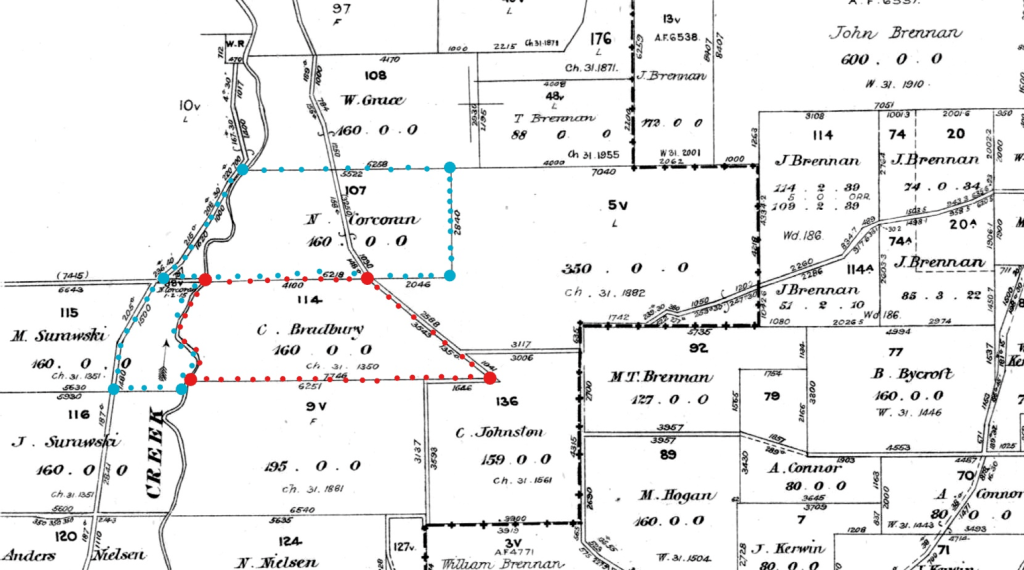

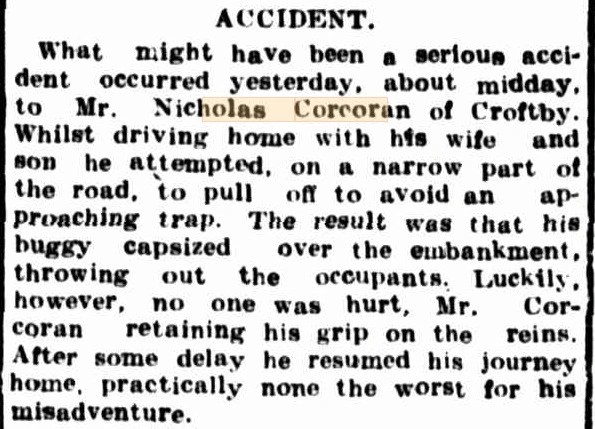

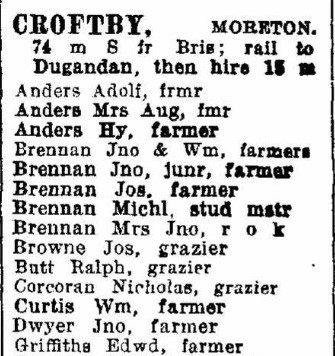

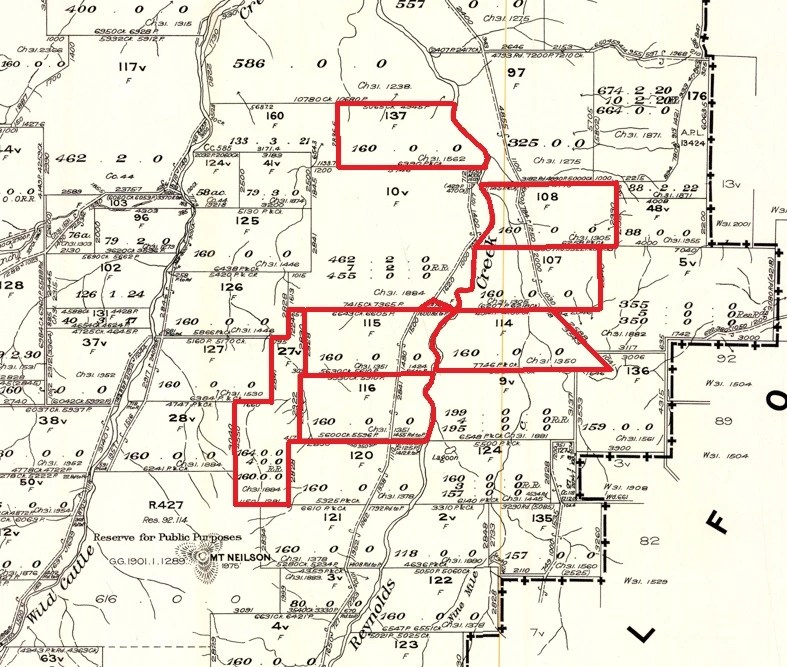

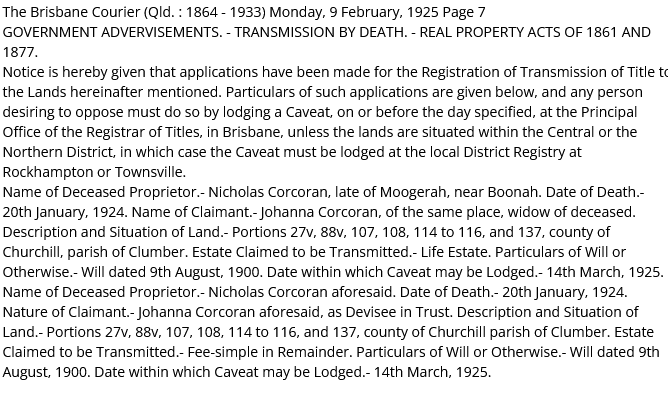

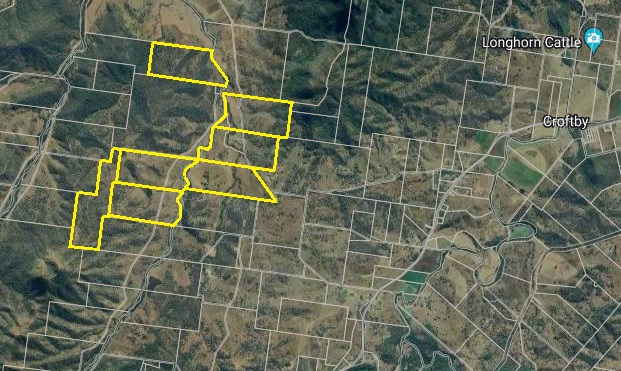

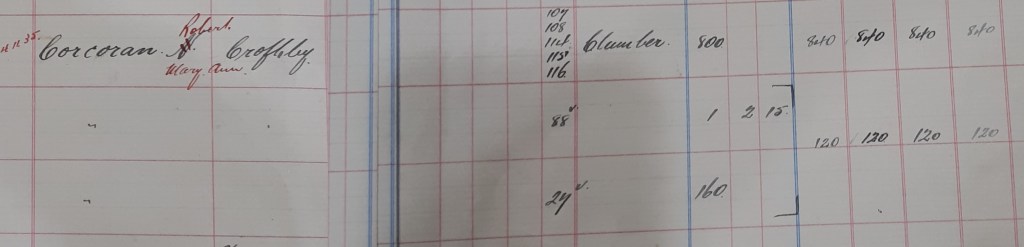

Having worked for the Wienholt Bros for about 16 years on their Fassifern Station, in May 1885 Nicholas shifted Johanna & the family (at that stage – 6 kids) to Moogerah, where he had selected land for farming & grazing. This section of land would have been originally part of Wienholt’s enormous “Fassifern Station”, which was then subdivided into land for selection by farming families. I’m guessing, that as Nicholas had worked for the Wienholts for many years and would have known how rich and fertile this land was, he probably would have had his eye on it for some time. It was located up behind (South West) the present-day Moogerah Dam, with permanent water for grazing & crop irrigation off Reynolds Creek & Nine Mile Creek. Nicholas’ original selection of land at Croftby was 160 acres.

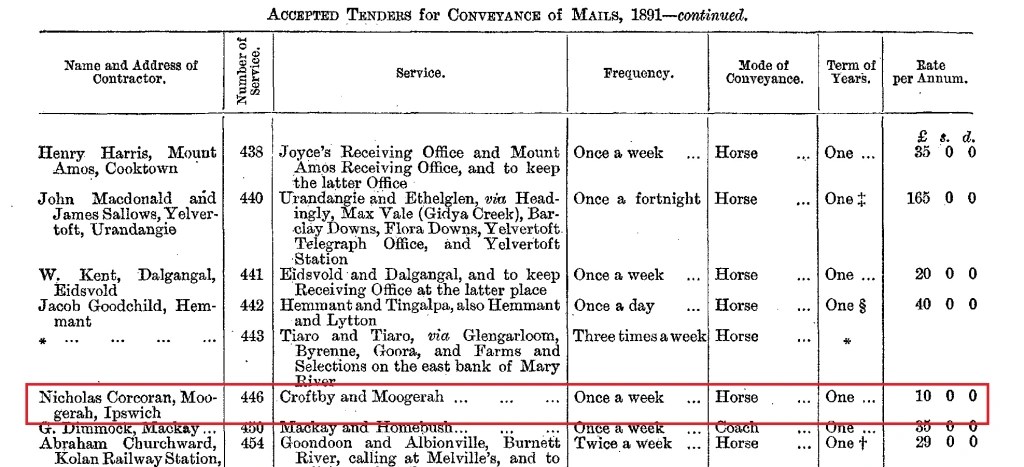

In the 1890’s Nicholas also had a contract to deliver the mail, once a week, in the Croftby area.

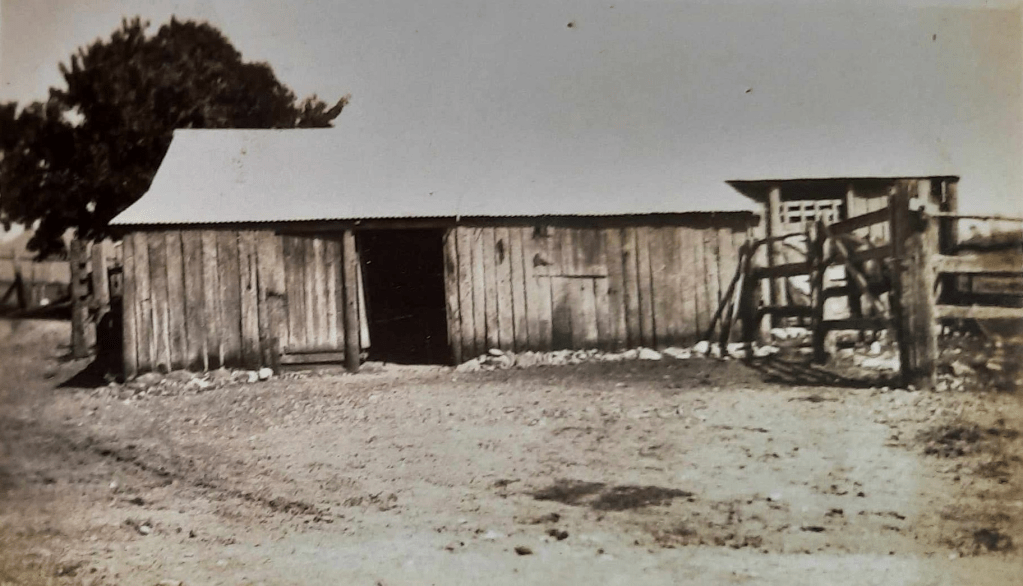

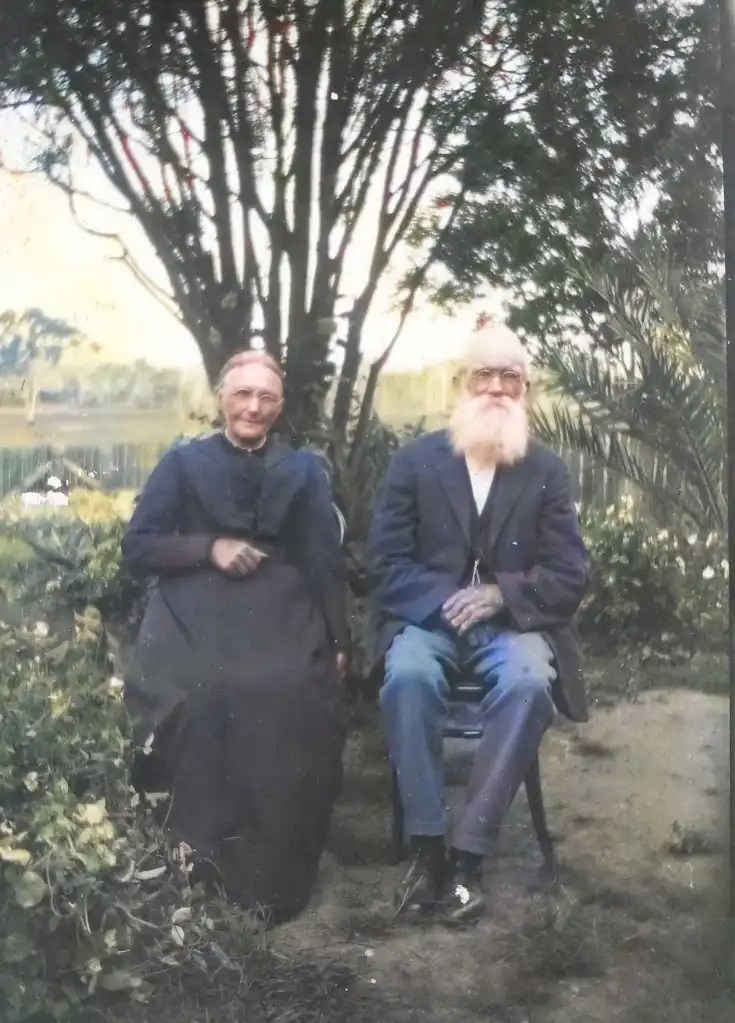

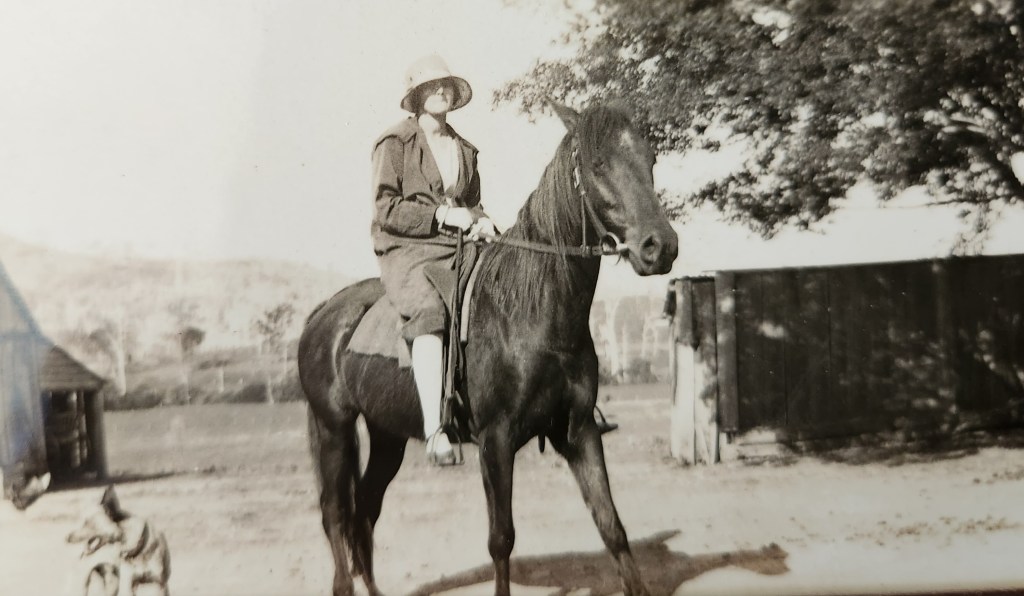

All the following photographs of the farm – “Rockmount” were taken 1920-1933.

Johanna’s mother Catherine Bradbury also acquired land in 1886, which later become part of the Corcoran land holding at Croftby. She would have been residing in Toowoomba at the time. Her husband Robert Bradbury had died 24 years earlier. The Corcorans ultimately had just under a thousand acres of prime farming and grazing land in the Fassifern Valley, at Croftby.

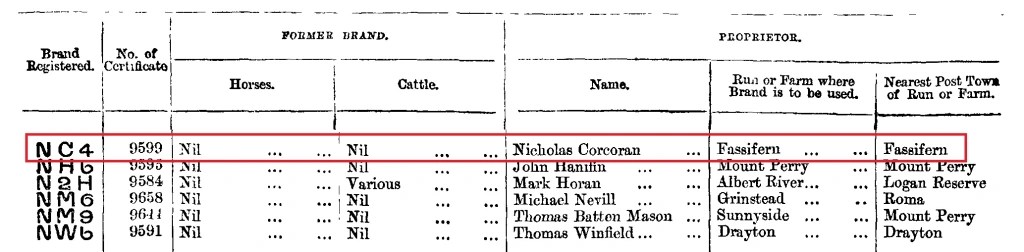

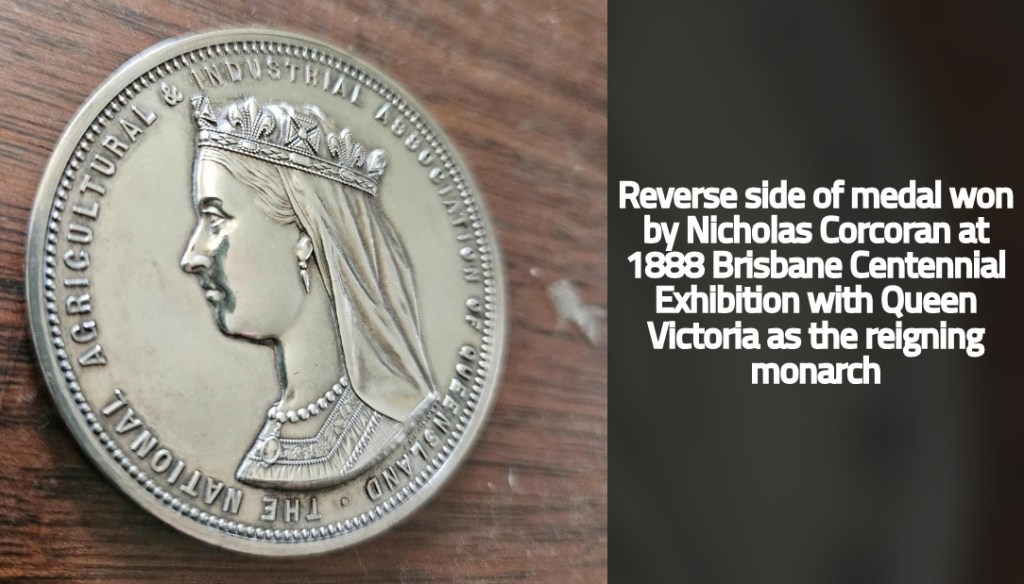

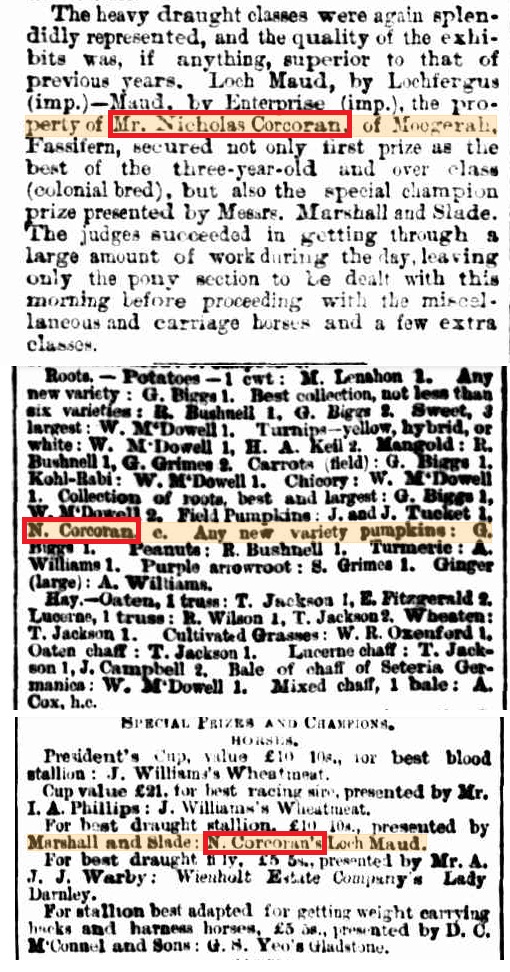

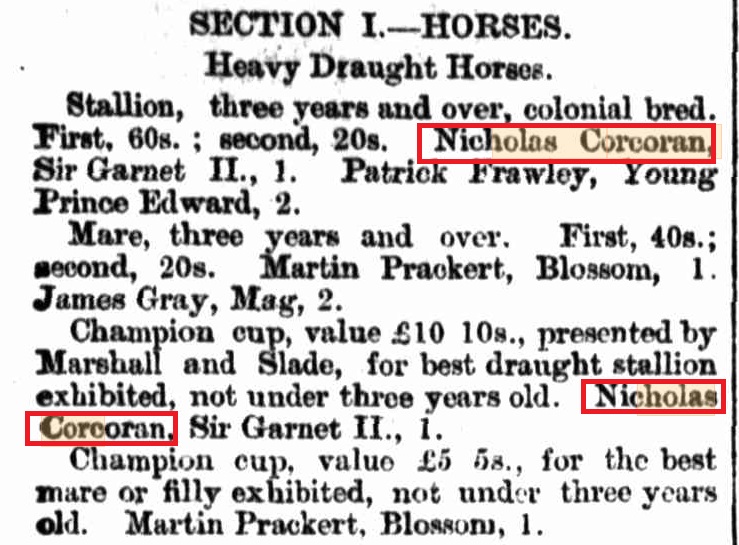

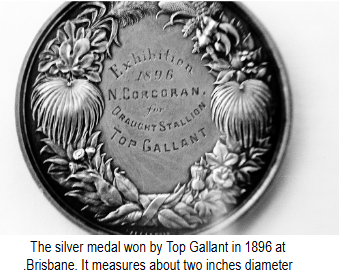

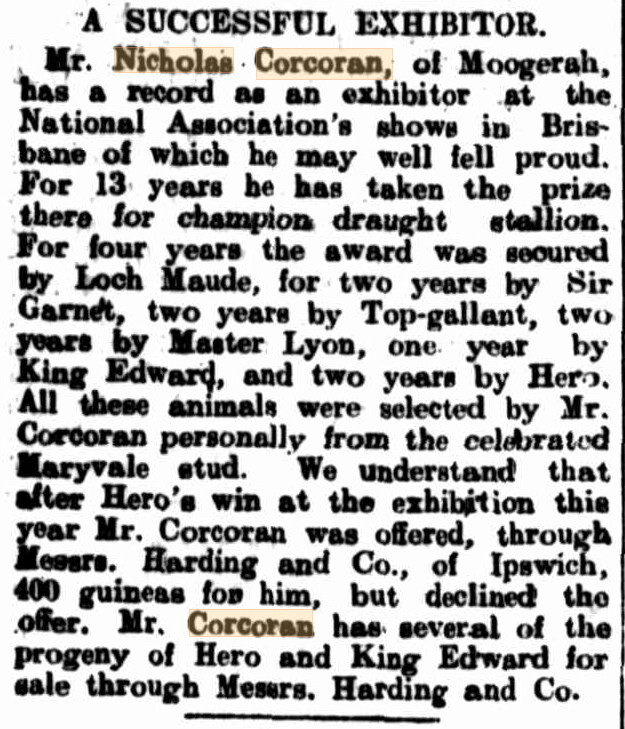

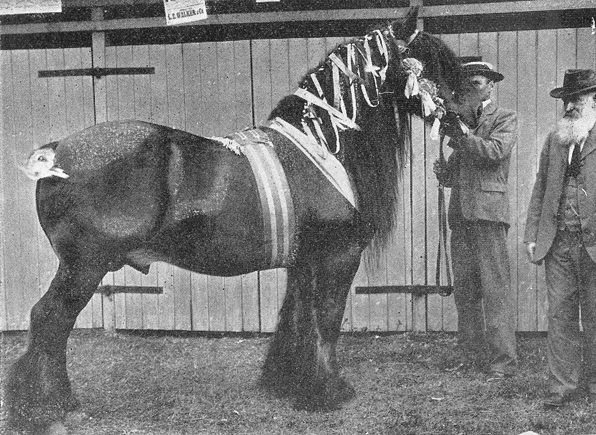

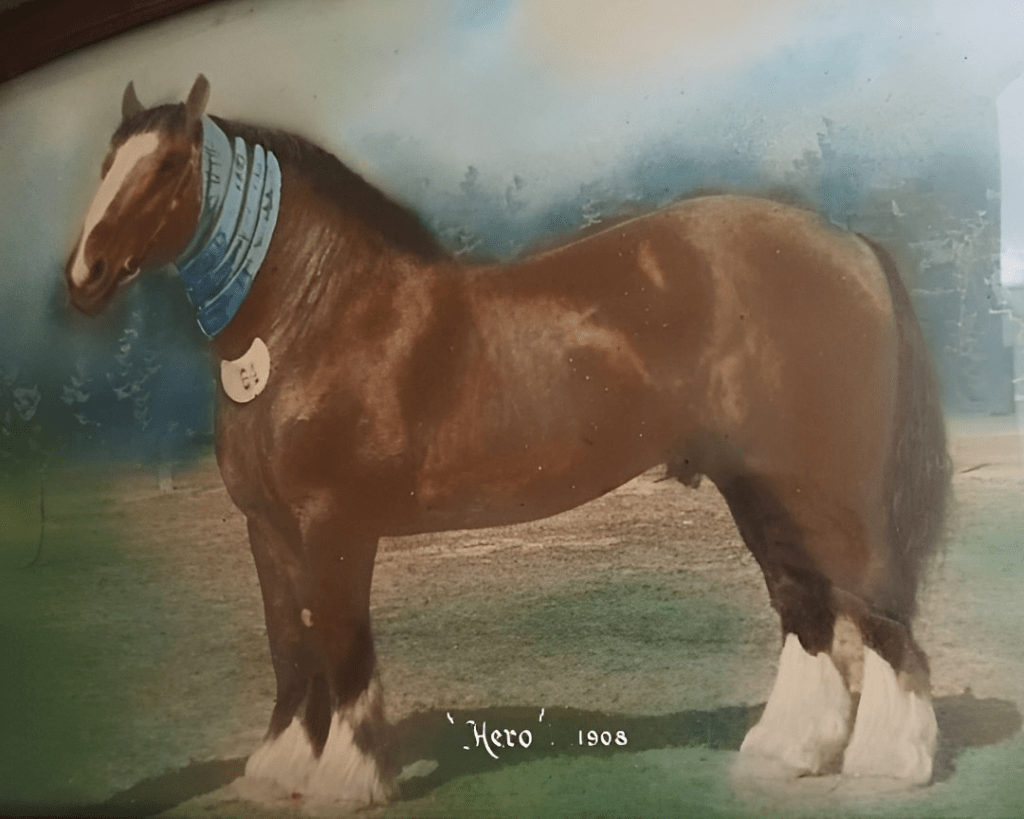

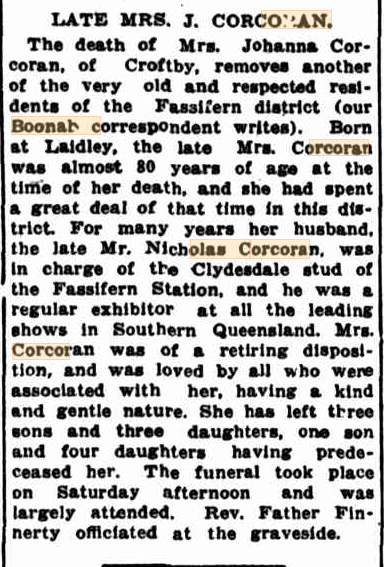

Nicholas was a champion breeder of Clydesdale horses & won many awards around South East Qld & also at the RNA show in Brisbane. He became one of the best authorities in Queensland on draught horses, which were the main farming implement before they were replaced by farm tractors. He was a foundation member of the Fassifern Agriculture & Pastoral Association, & later became a life member for his services.

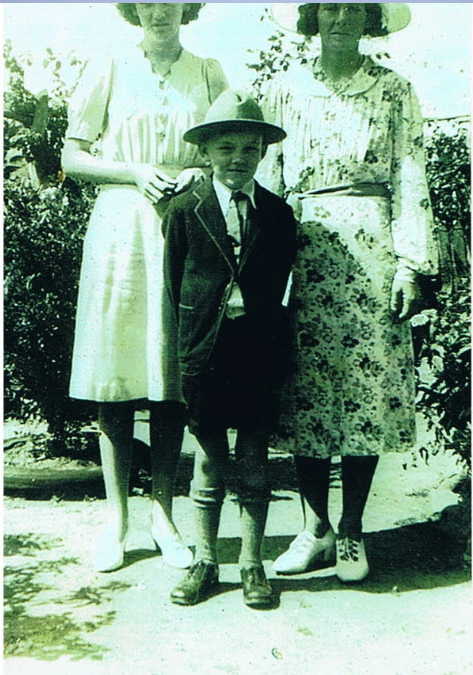

In researching ancestors, I always attempt to gain a perception of their lifestyles, political views, religious beliefs (if any), hobbies, sports, interests & just a general understanding of what their lives were like in those bygone eras. Most of the time, I have found that they were that busy just running a farm & raising a family, that there wasn’t that much spare time available, to engage in too many additional pastimes. We tend to take for granted these days, that we have time available for enjoyment of additional pursuits to enrich our lives. One hundred plus years ago, that was certainly not the case. Farmers & their families lives were full, in just running the farm, feeding, raising & educating the children & remaining fit & healthy. Another part of the lives of the Corcoran family that I found out, was their intense family values. Although having a full house at times, with nine children of their own to feed & raise, Nicholas & Johanna took in other kids who had lost their parents. Grandaughter, little May Madigan lost her mother at birth. Nephew Charlie Gilday also lost both his parents as a child & was raised on the farm. Another grandaughter, May Hoey who lost both parents at a young age grew up at Rockmount. My eldest brother John Francis Leslie Bermingham, was also raised by his grandparents & Uncles & Aunties on the farm at periods during his childhood. Handicapped grandsons – Kevin, Peter & Michael also spent time on the farm, under their care. Grandson, Edward Joseph Bermingham sadly died on the farm in 1922, aged 18 after being kicked by a horse. Many members of the extended family of that generation spent time at Rockmount during their childhood years. The Corcorans would never turn anyone away in their time of need & there was always a roof over their heads if they needed it.

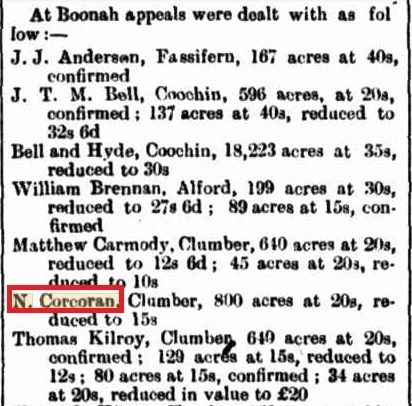

The early settlers, most of whom came from hard times in their countries of origin (in my case Ireland & Germany), were never going to take any injustices they encountered, lying down. If they felt that they were being ripped off by councils & governments with increasing rates & taxes, they were not backward in coming forward, to appeal against a decision.

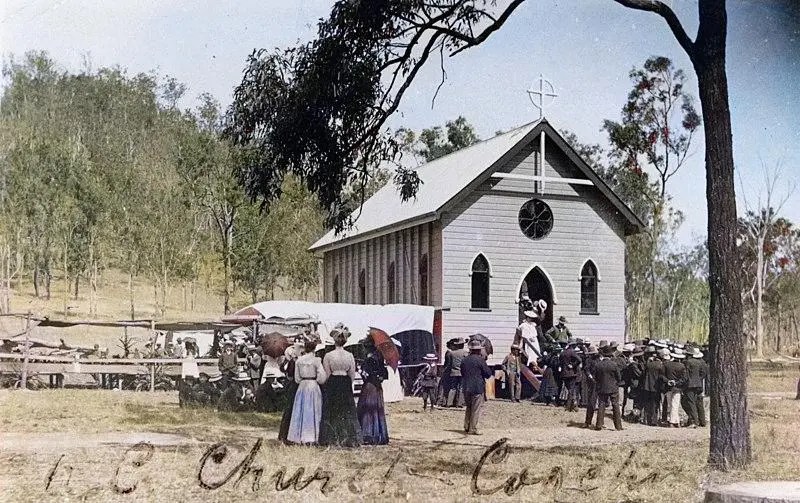

I noticed when researching the family history, the strong religious beliefs that most of the early settlers adhered to. Religion & churches were the pillars of most levels of society in Queensland at the time. The various religions and church factions didn’t always get along with each other. Some friction took place, mainly along the lines of faith & church administration. Nothing too serious! Whatever differences the local Churches had, certainly didn’t end up leading to fights, or wars breaking out. Some occasionally led to new congregations starting up. The reality was that they were not only meeting the spiritual needs of communities but also the social needs (which continue to this day). Farming, & life, in general, was pretty tough, so getting together the many farming families served more than one purpose. Sunday, traditionally the day of rest, was generally the only day people had off work, so the weekly church service gathered them all together to worship and catch up with what was happening in the community & around the district. It was certainly interesting to note that Catholics usually married Catholics and Protestants married Protestants. There were a few exceptions to the rule. The Churches and Religions had fairly strict codes of conduct.

Nicholas & Johanna Corcoran were devout Catholics, & brought their family up, to be the same. In the early days when Boonah and the Fassifern Valley were part of the Beaudesert Catholic parish, mass was often held at the Corcoran home at Rockmount. It may be worth acknowledging here, that as the writer of this article, I do not hold any religious beliefs whatsoever, but I do have the utmost respect for the people of these times & places, who did uphold the strict beliefs & teachings of their Catholic Church. It’s just a shame that the church that they held in such high esteam has slipped considerbly in its level of faith & moral structure, to the degree that in my opinion, I consider it to be a blight on modern society. The majority of the current day Catholic Church leadership should be behind bars.

Ellen and Margaret May were Johanna’s sisters and Min’s aunts. Both Ellen and Margaret May died within six months of each other—Ellen in childbirth along with her baby son, and Margaret May from the flu three days after Little May’s birth.

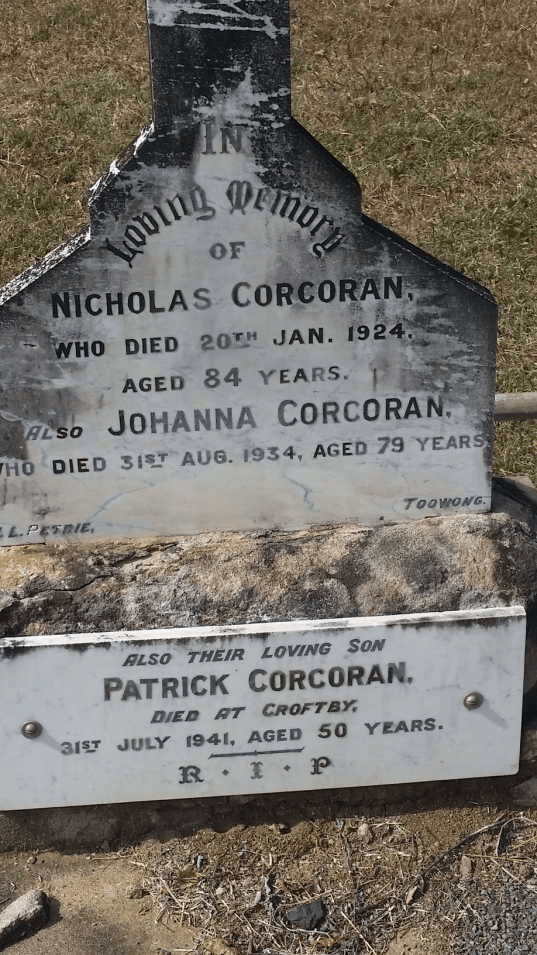

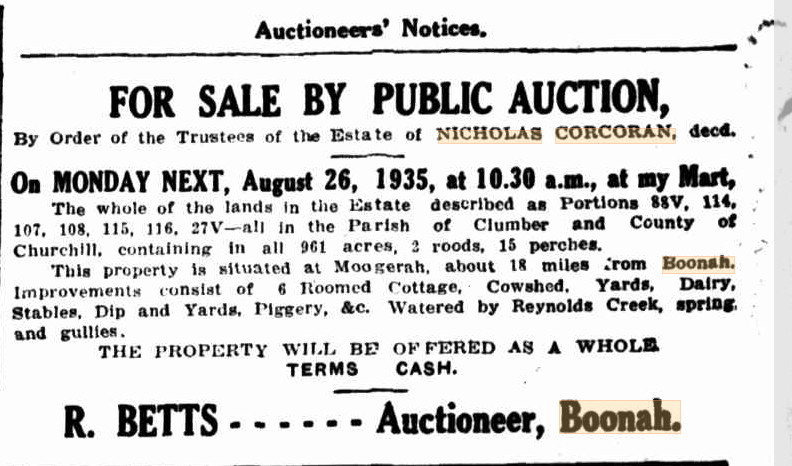

Nicholas Corcoran died on 20th January 1924 at the age of 82 and was buried in Boonah Cemetery, Queensland.

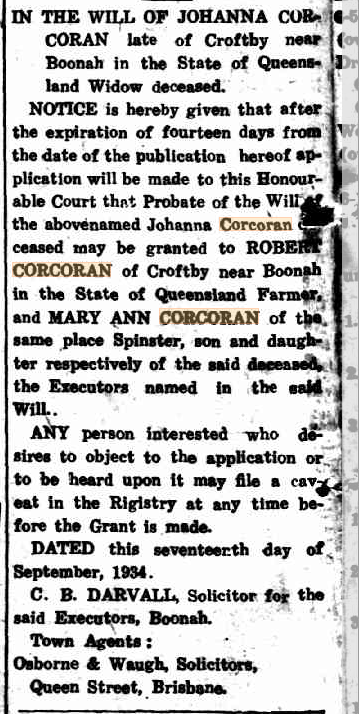

Johanna Corcoran died on her 80th birthday, the 31st August 1934, at home on the farm “Rockmount” at Moogerah, near Croftby. She was buried beside her husband, Nicholas in Boonah cemetery.

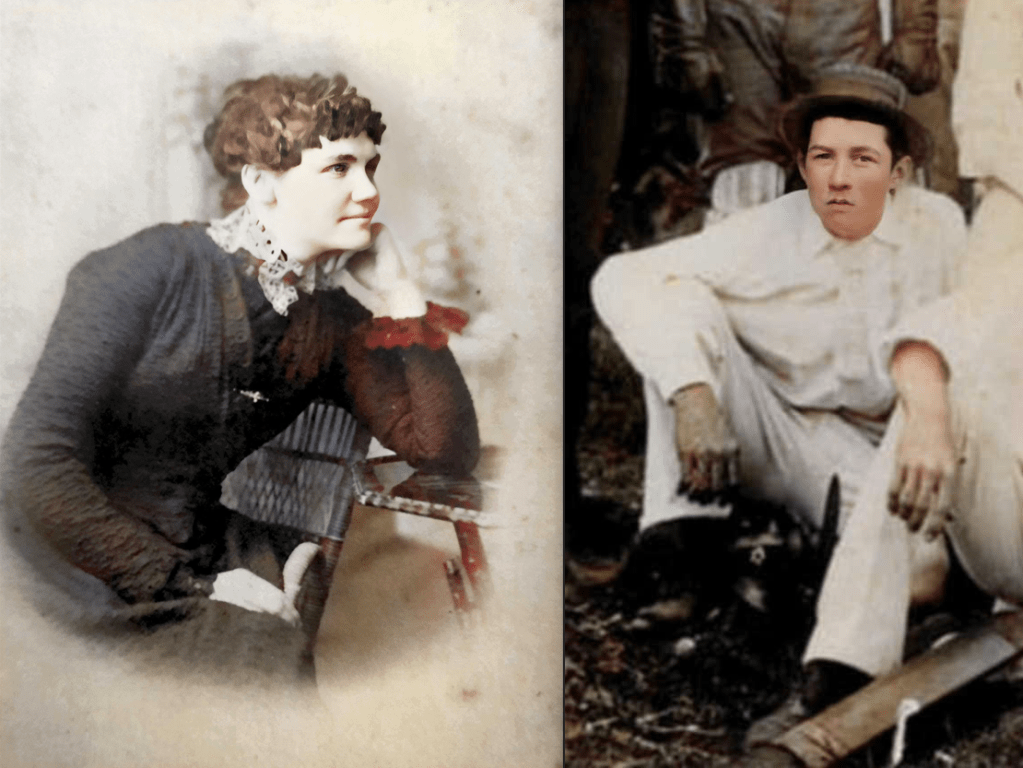

Above shot of Mary Ann (Minnie) & Johanna Corcoran was probably taken shortly before Johanna’s death in 1934.

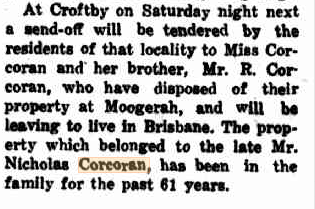

Uncle Bob Corcoran taken at the farm c1934. Rockmount was sold to Robert (Uncle Bob) & Mary Ann (Aunty Min) Corcoran who were the children of Nicholas and Johanna on the 4th Nov 1935 and it was valued at £960. Valuation on the “Rockmount” property in today’s (2024) currency would be somewhere in the vicinity of $15 million.

In 1948 Robert & his sister Minnie, Corcoran sold the property & moved to New Farm in Brisbane.

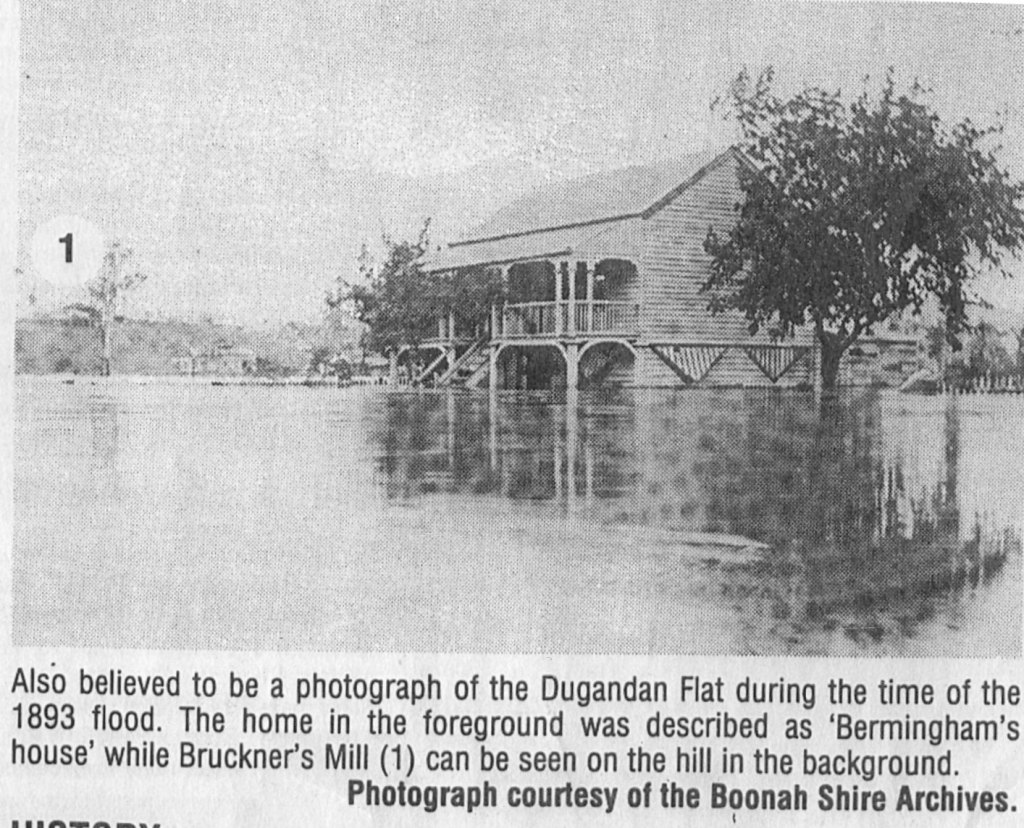

Nicholas & Johanna Corcoran’s oldest daughter – Catherine Mary, born 1876, grew up on the family farm at Moogerah in the Fassifern Valley & later married a local tradesman, carpenter/cabinet maker Edward Bermingham from Boonah. They lived at Dugandan, just on the southern outskirts of Boonah township. Edward & Catherine had six kids, one of whom was my father – John Francis (Jack) Bermingham.

See the following article I’ve also done on Peter Bermingham & his descendants https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/02/22/peter-bermingham/

With so many children (as did many of the original settler families), the Corcoran family desendancy trail branched out to all parts of the state of Queensland. They lived and raised families of their own in Brisbane, Gympie, Bundaberg, Rockhampton, Mackay, Townsville & many of the inland regional districts. So, from the 1800’s, into the 1900’s & onwards to the 21st century those ongoing families & descendants have spread further afield & moved interstate, to live & have families who have now spread across Australia. The original Corcoran’s were a true Australian pioneer family, in every sense of the word.

Nicholas Corcoran’s identity didn’t stop with his passing. Current living descendents of Nicholas Corcoran who traveled over from Ireland in 1864 to start a new life here in Australia, would number well into the hundreds. Our own delightful little grandaughter, Samara is also a descendant of Nicholas & Johanna Corcoran, making her their Great/Great/Great Grandaughter.

With thanks to my cousin Mary who helped me with many of the photos & records of the Corcoran family history. Also, a special mention for the assistance from Sharon Racine who is a local historian from the Fassifern Valley area. Sharon found many old records from the Corcoran family. Greatly appreciated.

Geoff Bermingham – great-grandson of Nicholas & Johanna.