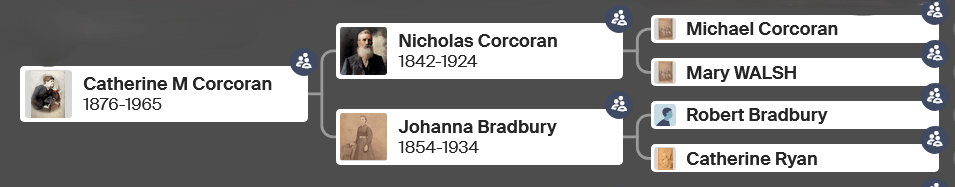

Catherine Mary Corcoran, born 20 November 1876, died 5 February 1965.

It’s common to perceive grandparents as always being old because they have always held that role in relation to us. However, this perception is simply a natural result of the generational gap. They, too, were once young, full of hope, enthusiasm, dreams, and aspirations long before becoming grandparents.

This story is about my grandmother, Nana Catherine Bermingham. I’ve mentioned her in some of my other blog stories about my ancestors, and in doing so, I feel I may have been a little harsh on her.

While compiling this story, I’ve taken a few liberties. I try to stick closely to the facts when writing these articles, but in this instance, I’ve decided to connect a few of the dots myself.

As the eldest daughter and second-oldest child, Kate, as she was always known, would have taken on a fair amount of responsibility in helping to raise her younger siblings. The Corcorans lost two children in infancy, as did many early settler families.

The family were devout Irish Catholics, and all the children were brought up with strong religious values.

Kate’s father, Nicholas Corcoran, an Irish immigrant, was a farmer and grazier who also bred champion Clydesdale horses. Her mother, Johanna Bradbury, was the daughter of a ticket-of-leave convict and an Irish workhouse orphan girl.

As for Kate, I only ever knew her as a very old lady. She was seventy-eight when I was born and passed away at eighty-nine, in 1965. My memories of her are of an elderly, bedridden woman in the final years of her life. I remember visiting her in Boonah often; on one occasion, shortly before her death, she was brought out of her bedroom to join us for Christmas dinner. I was ten when she died.

As mentioned, I feel I may have judged her too harshly in some of my previous ancestry pieces. In many ways, what I hope to do here is set the record straight.

Catherine Mary Corcoran was the first daughter in a family of eleven children to Nicholas and Johanna Corcoran. They lived on their family farm in the Fassifern Valley, a few hours west of Brisbane, nestled at the base of the Great Dividing Range.

When I look at photos of Kate in her later years, I see her as I remember her — a tough, old woman who, though always kind to us, rarely seemed to have much to smile about. As a child, I often wondered why she showed such a hardened exterior. Now, having delved deeper into her life, I’ve begun to understand the mental and physical challenges that likely shaped her into the person she became.

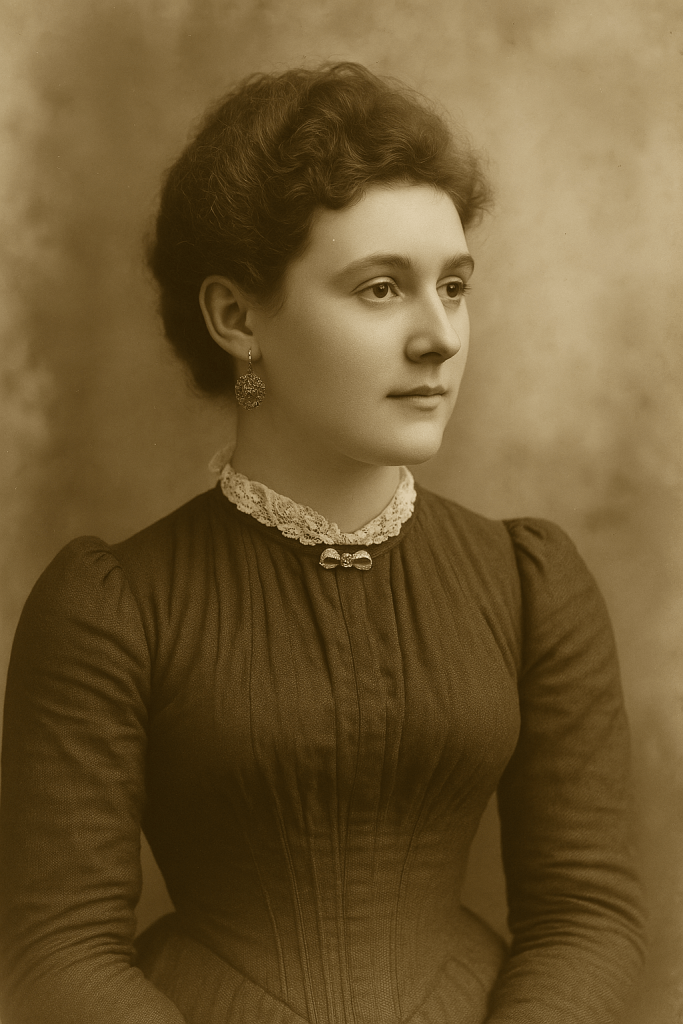

Using the earliest original photograph I have of her (at the head of the article) is one that I’ve digitally enhanced using AI. I see a young woman with the hopeful expression typical of her time. She was an attractive girl with the same dreams and expectations most young women had back then. Raised in a loving home in the beautiful Fassifern Valley, she would have received a basic early education, enjoyed life on the family farm, and had a well-balanced childhood. In much the same way as modern-day girls contemplate their futures & who their partners may be, I’m sure she dreamed of marrying a local farmer, merchant, or tradesman, and of raising her own family in circumstances similar to her own upbringing.

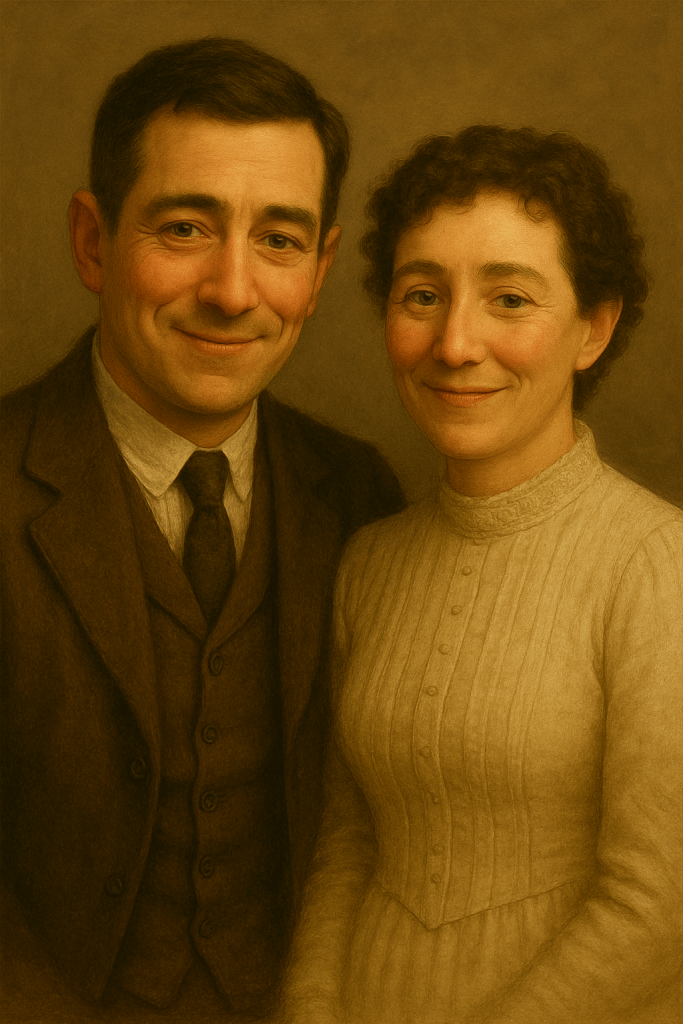

As fate would have it, she attracted the attention of a handsome local lad—a successful young carpenter who had recently completed his trade apprenticeship. He was also an excellent sportsman, well-known as a talented cricketer in the district, and an early member of the local West Moreton Volunteer Regiment in Boonah. His name was Edward “Ned” Bermingham. He was considered quite the catch—a handsome, athletic Irish Catholic lad who met all of Kate’s parents’ expectations for a future husband. I’m sure Nicholas and Johanna Corcoran were delighted when their eldest daughter fell in love with this local young tradesman.

However, things took an unexpected turn when Kate became pregnant in 1903. The couple had a hastily arranged marriage later that year, but it didn’t dim their optimism. Kate and Ned still had the world at their feet and eagerly looked forward to the birth of their first child.

On 24 June 1904, the couple’s first baby son, Edward Joseph Bermingham, was born. He was soon followed in 1906 by another son — my father, John (Jack) Francis Bermingham. Then came Kevin Patrick in 1908, Johannah Mary in 1910, Peter Nicholas in 1912, and Michael Bowen Bermingham in 1915.

In 1910, the couple had purchased the Dugandan Joinery Works from Charles Vincent, the master tradesman with whom Ned had completed his apprenticeship.

Over the next few years, Ned’s carpentry and joinery business was booming. Life was good.

However, as the family grew, a troubling reality became apparent: three of the boys — Kevin, Peter, and Michael — were affected by an intellectual disability. The boys grew up in a loving home, but it soon became clear that they would always need ongoing support. Raising one child with such challenges in a family of six kids would be hard; raising two would be difficult; raising three would be overwhelming. Fortunately, there was plenty of extended family in Boonah and the Fassifern Valley to offer help and support.

Looking at Kate, I see a vibrant young woman on her wedding day—yet only a few years later, she and Ned faced the heartbreaking challenge of raising three sons with intellectual disabilities. Such circumstances would have profoundly changed their lives. Ned was known for his cheerful and easygoing nature. He played district-level cricket, was an accomplished marksman, and later became deeply involved in local horse racing, serving as secretary and treasurer of the Boonah Turf Club for many years—all while managing a successful business.

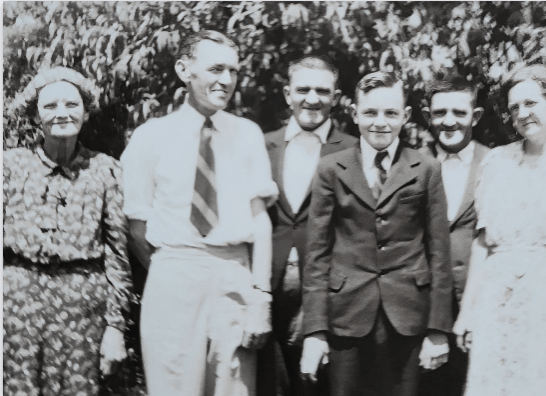

Having three sons with special needs must have been devastating for both Kate and Ned. In the few surviving family photographs, you can see the change in Kate — from the beautiful young bride to a weary woman hardened by years of struggle and sorrow. I believe Ned threw himself into his work and sporting pursuits as an escape from the harsh realities of home life, leaving Kate to shoulder most of the responsibility for raising the boys.

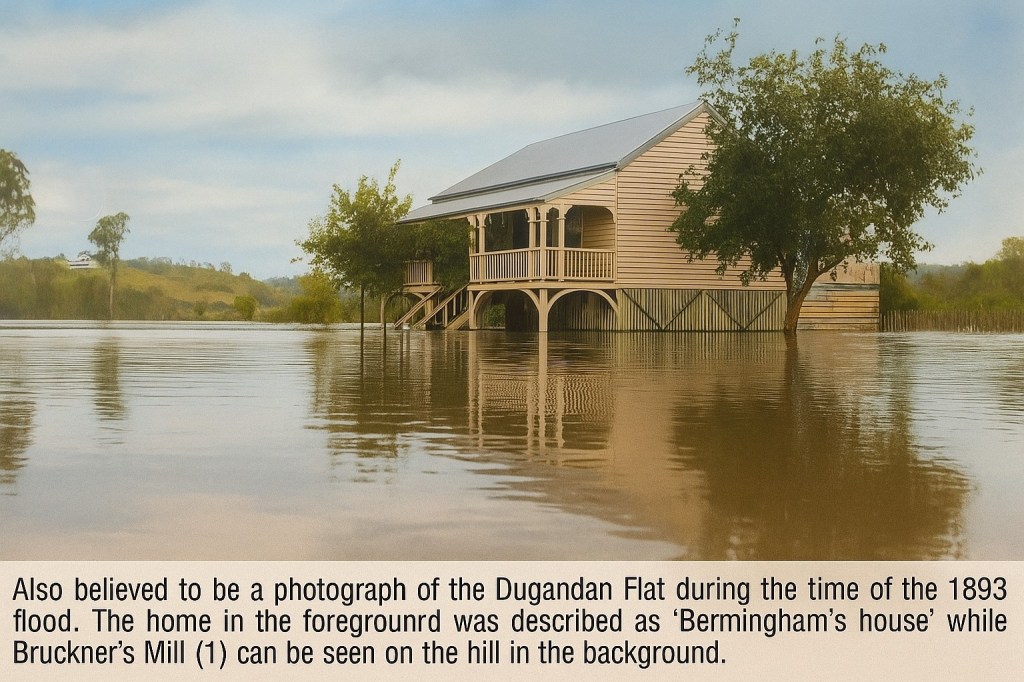

If life wasn’t already tough enough, the Dugandan Flats—where they lived—were flooded many times during the severe floods that struck in the first half of the twentieth century.

In their younger years, family life may have seemed fairly normal, but as the boys grew older and stronger, life inevitably became much harder. With both parents aging, controlling them would have been increasingly difficult. Kevin, Peter, and Michael often spent extended periods on the Corcoran farm in the Fassifern Valley, where they enjoyed greater freedom and understanding.

From all family accounts, they were never a threat to anyone — simply innocent souls unable to care for themselves independently. Today, with proper assistance, their lives would have been very different. Back then, they were well cared for by their immediate and extended family, who loved them dearly and did their best to support them.

If life had not already dealt Ned and Kate a cruel hand, tragedy struck again when their firstborn son, Edward Joseph Bermingham, was killed in a farm accident at just 18 years old in 1922.

By the mid-1930s, the family dynamic had changed dramatically. The boys were now adults, their parents were in middle age, and Kate’s parents, Nicholas and Johanna Corcoran, had both passed away. My father, Jack, and his sister Molly were pursuing their own careers. Jack had married and had a son, John, but the marriage ended, leaving him with custody of the child. While Jack worked across Queensland as a telephone linesman, his young son was cared for by Kate and Ned, with help from the many Corcoran aunts and uncles.

In 1944, Ned passed away at the age of sixty-six, leaving Kate alone to care for their three sons, who by then were grown men aged thirty-six, thirty-two, and twenty-nine, respectively. They often grew frustrated with their own limitations, while Kate—now nearing seventy—found it increasingly difficult to look after them. My brother John often remarked, “Those boys were hard work.”

In truth, she carried an enormous burden — raising three dependent sons largely on her own. Her motherly instincts ensured that she never stopped loving them, but the toll on her physical and emotional health was immense.

At times, Kate must have wondered what she had done in her God’s eyes to deserve the life she was given. She was a devout Catholic, whereas with Ned, lets just say that he seemed to hold a weaker belief structure. His religious practice appeared more a matter of duty—attending church simply because it was expected of him. Her suffering and frustrations often overflowed into her treatment of her husband, her other two children — Jack and Molly — and her grandson John.

In John’s words, “As a religious bigot, she ruined the lives of Dad, Molly, and nearly me with her religious fanaticism.”

I truly believe she felt that God and her faith had somehow abandoned her. Though she never lost her rigid religious convictions, it’s hard to blame her for having those thoughts. For that once beautiful, optimistic young woman to endure such relentless hardship and tragedy, she coped in the only way she knew — by clinging to her faith, because no one else was there to help her. She lived in an unending cycle of care — twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, three hundred sixty-five days a year — forced to keep going for the sake of her sons. It’s no wonder she looked utterly exhausted as she grew older.

With her husband dead and her own strength fading, she eventually had to make the heartbreaking decision to place the boys in an asylum, hoping they would receive proper care.

After Ned’s death, Kate suffered from severe depression, grieving the loss of her husband while struggling with the guilt of institutionalizing her sons. Evidence also suggests that she became involved with the QCWA (Queensland Country Women’s Association) during this time, likely as an effort to get out and break the cycle of depression she was trapped in. Though I am not a religious person, I can understand why she turned so deeply to her faith throughout her life. None of us can truly comprehend the suffering she endured while raising her three intellectually disabled sons—and losing another—during such a difficult era.

It’s important to remember that, at that point in history, assisted mental health care was virtually nonexistent for individuals — especially for families with children living with disabilities. People had to make do with what they had; in other words, they simply had to keep going. Failure wasn’t an option. For those who couldn’t cope, the only alternative was often the bleak, overcrowded asylums that operated at the time.

It is somewhat ironic that the once young woman who had started her family all those years ago had grown frail and mentally deteriorated, now requiring the very help she had so selflessly given to others throughout her life. Fortunately, her daughter, my aunt Molly, stepped up to fill the void and care for her mother during her final years.

As I’ve uncovered more about our family ancestry, I’ve come to understand the life-changing events that shaped Kate and Ned’s lives as they began their family. As children, we often saw our elderly relatives—whom we perceived as grumpy, dowdy, and unsmiling—and formed opinions about them without knowing the full story behind the hardships they faced throughout their lives.

The reality of Kate & Ned’s lives mirrored that of many other Australian families in the early to mid twentieth century who had children with mental or physical disabilities. The vast majority faced their adversities with courage, as they simply had no other choice. They suffered in silence.

Today, medical science has advanced to the point where couples can undergo various pre-natal tests to detect serious health issues in an unborn baby — and they are given choices that simply didn’t exist in Kate and Ned’s time. Back then, they faced whatever came their way with no warning, no modern support systems, and no medical guidance.

You’ve got to hand it to the old girl—and I say this with respect—she held firmly to her faith until the very end of her life. The local Catholic priest visited her every week to give her Mass at her bedside. Many others would have abandoned such steadfast beliefs long before then, especially after enduring all the hardships she faced throughout her life.

I’m certain that her son, Jack—my father—and her daughter, Molly, had become somewhat lapsed in their faith. If not entirely, then at least in the depth of their convictions later in life, partly because of their mother’s uncompromising hardcore devotion to her Catholic beliefs.

It’s worth noting—and this observation may be entirely coincidental—that Kate’s mother, Johanna Corcoran (née Bradbury), was as much of a devoted “God-botherer” as Kate herself, if not more so. Johanna was a deeply committed Catholic, and her mother, Catherine Bradbury (nee Ryan), was equally devout, attending her local church in Toowoomba every day.

In contrast, my research into the male side of the family suggests that the men were far less zealous in their Catholicism. My father, Kate’s son Jack, along with his father Ned and Ned’s father Peter Bermingham, all appeared to practice their faith with much less intensity. As I mentioned, this may simply be a coincidence—that the men in the family line tended to be less devout than their wives.

One thing I know for certain is that I now hold immense respect for my grandmother, Kate Bermingham. As my brother John said on more than one occasion – “She was a woman who had a lot to put up with.”

Full disclosure……I have taken the liberty of using AI to enhance the very few photographs in existence of Kate & Ned. When AI is used, it can sometimes over-enhance photos & images. Make of them what you will.

View the following article on Kate’s husband Ned, & my father, Jack here https://porsche91722.com/2023/02/22/peter-bermingham/

The chapter on the lives of the three boys – Kevin, Peter & Michael is here https://porsche91722.com/2025/01/13/the-story-of-kevin-peter-michael-our-family-missing-persons/

There are also many other stories on my family ancestry & other topics here https://porsche91722.com/category/uncategorized/