Our family, on both sides, comes from the Boonah–Fassifern district. We often visited our grandparents on both Dad’s and Mum’s sides, along with uncles, aunties, cousins, and many other extended family members. All our ancestors, going back to our great-great-grandparents, had strong ties to the Fassifern Valley. Most of the originals settled in the district as farmers after immigrating from Ireland and Germany in the 1800s.

As a young child, I often felt as though we were related to half the population of the district. Since both Dad and Mum grew up in the Fassifern Valley, they also had many friends and acquaintances of their own. We were constantly being introduced to people I had never met before — “This is Uncle so-and-so,” or “your cousin so-and-so,” or “Great Auntie so-and-so.”

As a kid, it was nearly impossible to remember everyone on that ever-growing list of relatives, who they all were, and where they fit into the family tree.

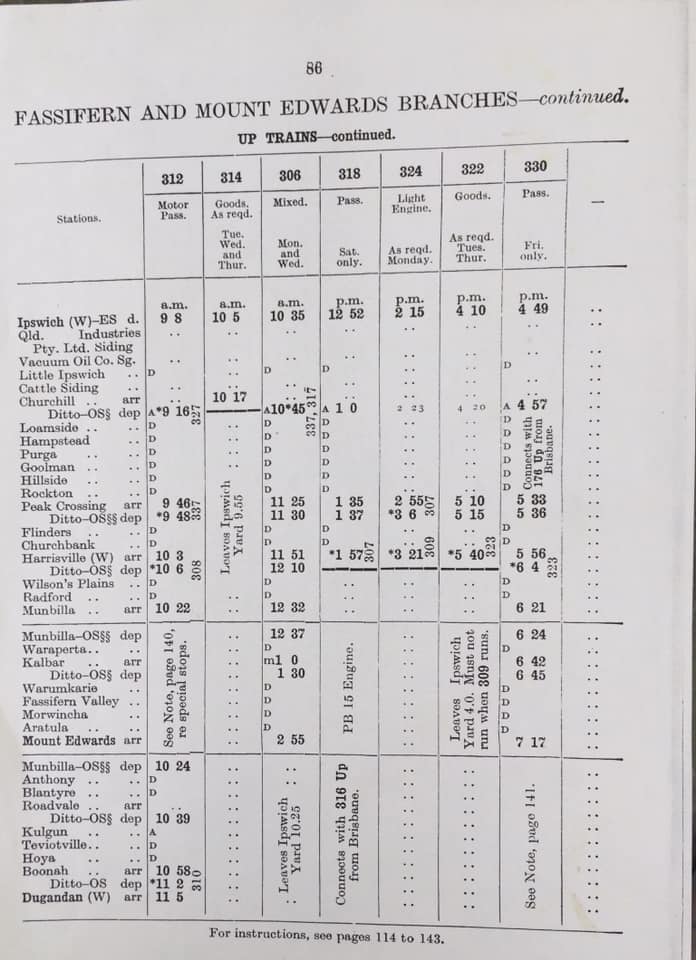

However, this blog article focuses on another part of the history of the Fassifern Valley – the railway and how it contributed to, and became a significant part of, the development of the Boonah/Fassifern district.

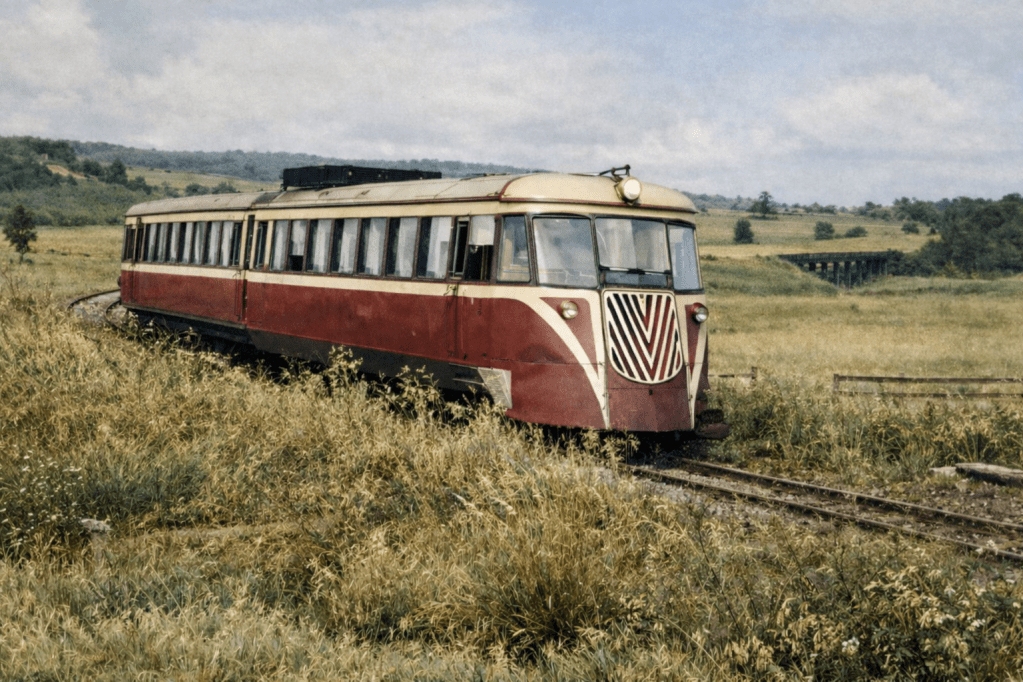

This stretch of railway holds many memories for me, as I often travelled along it with my father when we visited Boonah. I was only about five years old the first time I rode the old railmotors to Boonah.

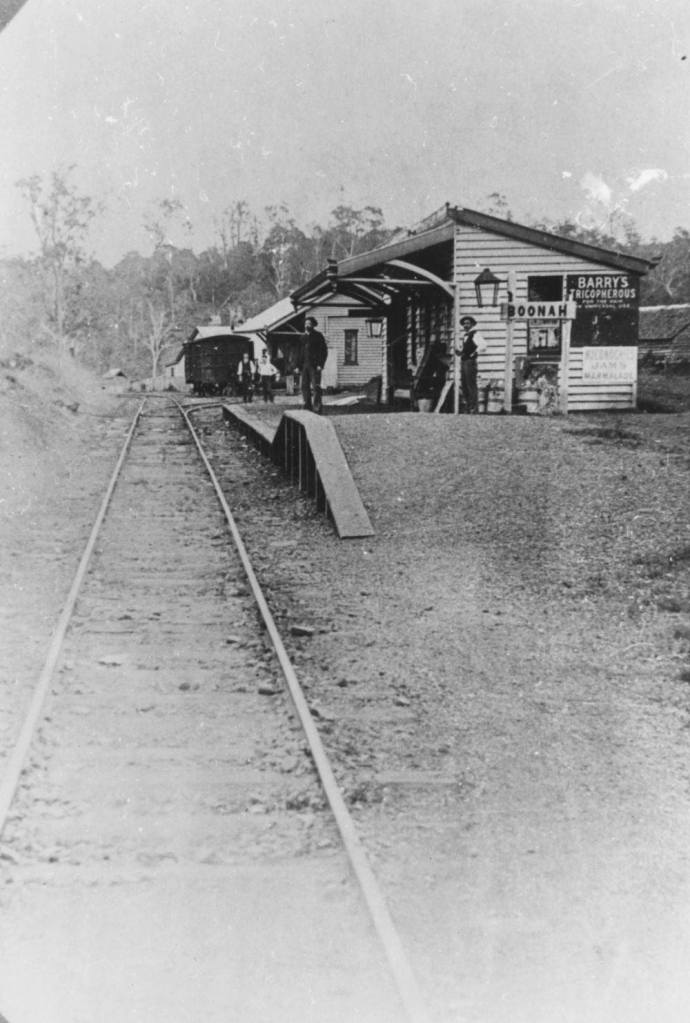

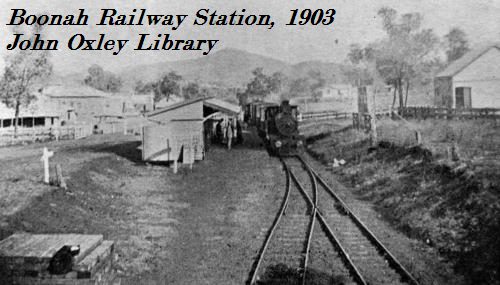

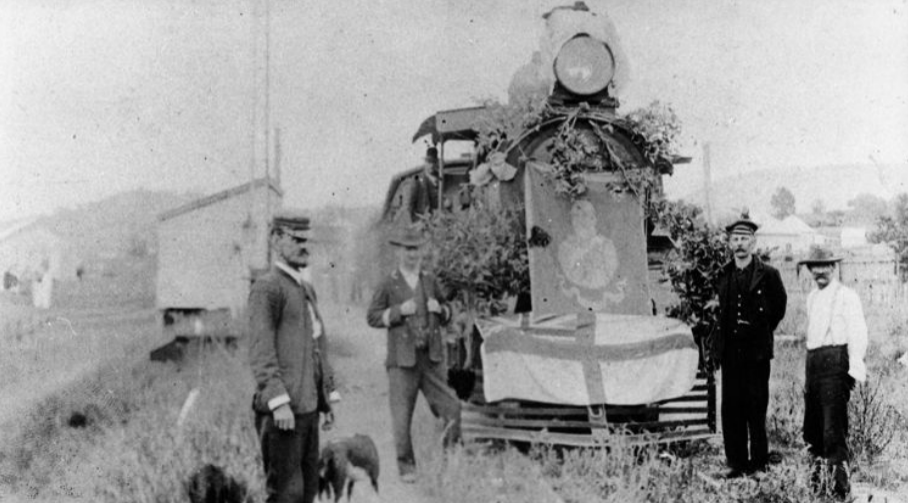

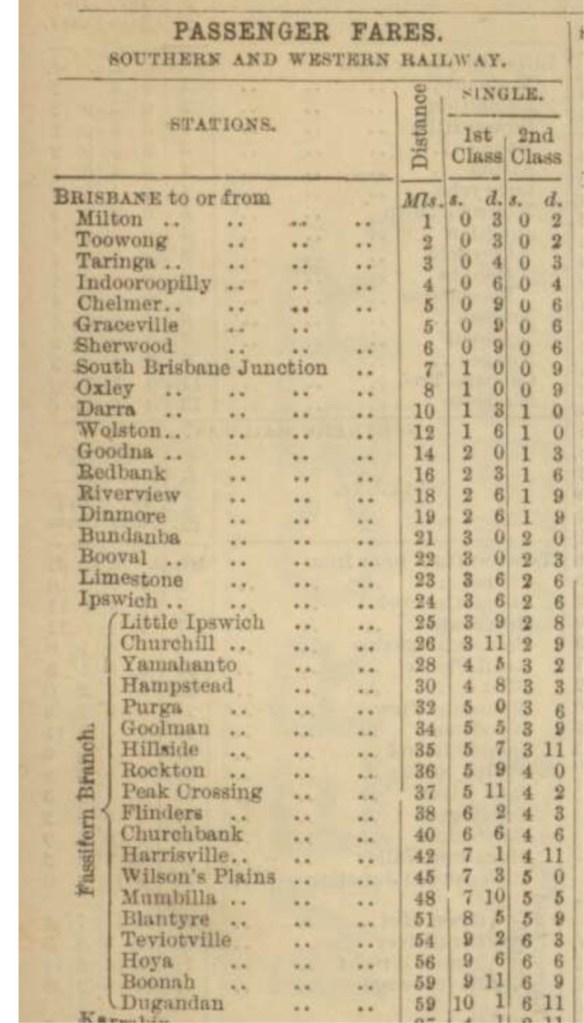

The line was first opened in 1882 to Harrisville, and later extended to Boonah and Dugandan, with the extension completed on 12 September 1887.

My grandfather, Edward Bermingham, was one of the earliest travelers on the branch line.

In late 1887, at the age of nine, young Ned traveled by train from his parents’ farm on the South Pine River, on Brisbane’s northern outskirts, to Boonah. He went to live with his older half-brother, Senior Constable John Bowen Dunn & his wife Martha. John Dunn had just been appointed as the town’s first police officer. Notably, the establishment of Boonah’s police station and the arrival of its first resident officer coincided with the opening of the railway.

Our family members certainly had a fascinating connection to rail travel. My parents actually first met on a train trip back to Boonah in about 1947. They were both traveling home on a railmotor to see their respective families, who, as it turned out, lived about 300 mtrs apart, in Macquarie St, Boonah. When they were married a year & a half later, the couple immediately boarded a train to North Queensland for their honeymoon.

Many of my ancestors—some of the original settlers in the district—with family names such as Corcoran, Muller, Kruger, Kubler, Lobegeiger and Bermingham, often travelled to & from the district by the trains. They were primarily farming families, and as such, relied heavily on the freight services of the railway to transport their produce and livestock to market.

The Fassifern railway, therefore, holds both deep connections and a sense of nostalgia—not only for me but for our entire extended family. Through our ancestral ties, we share a lasting bond with the Fassifern district and the town of Boonah.

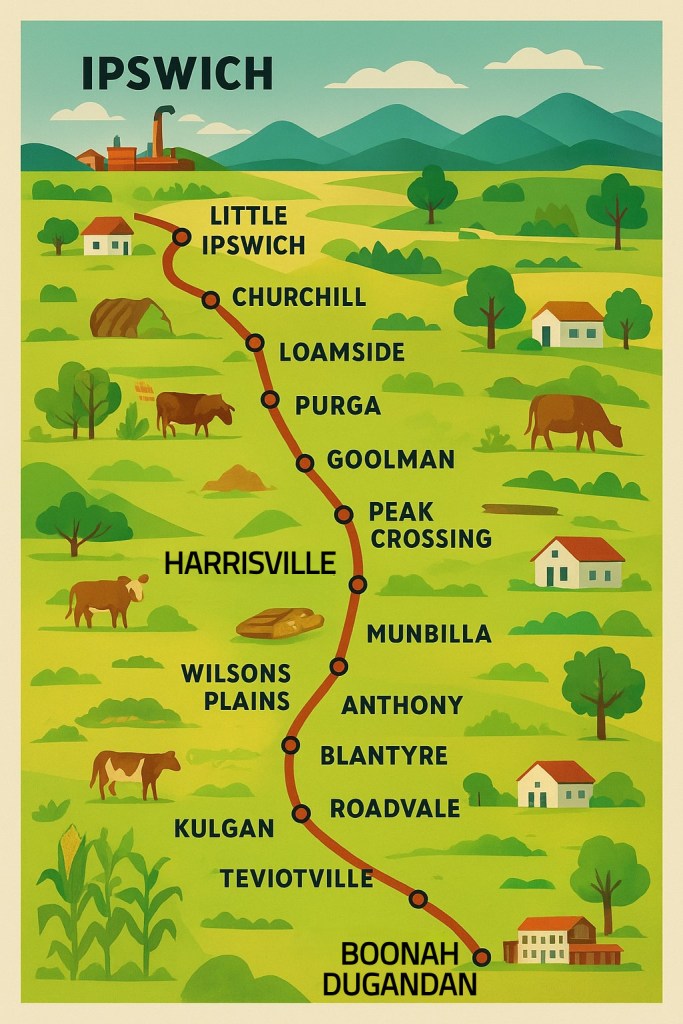

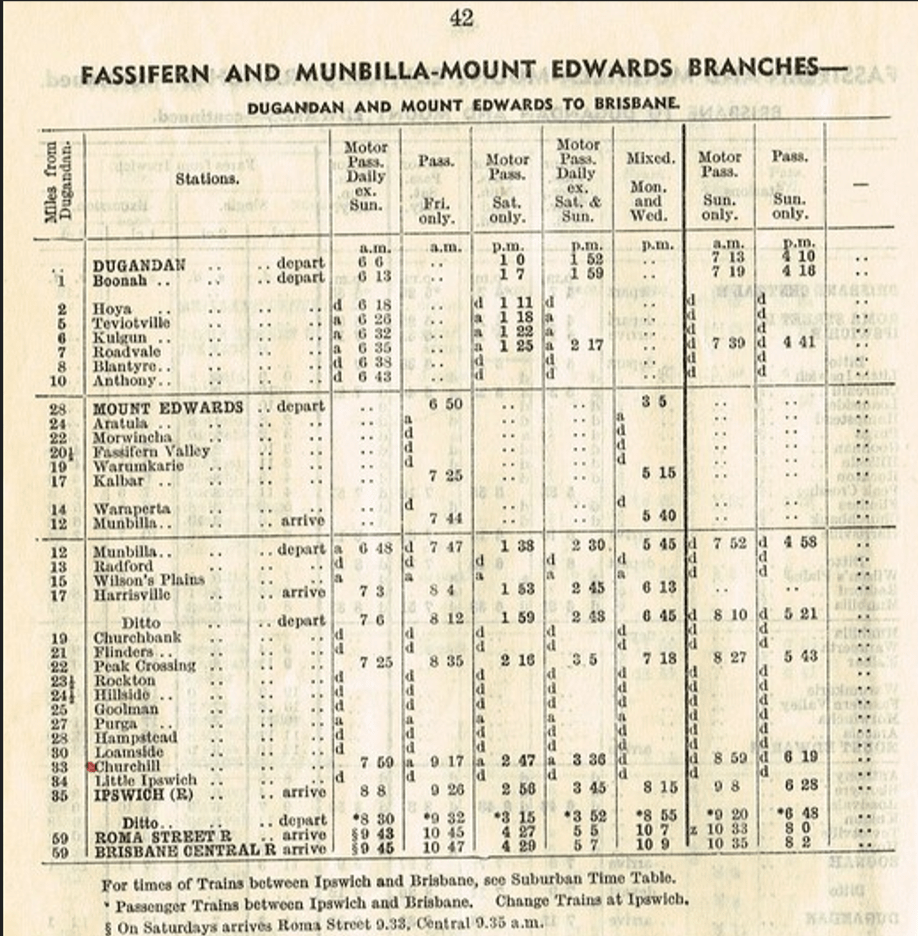

Let’s travel the line station by station, imagining how it might have felt from 1887 through the district’s development years and right up until 1964, when the line was closed. During this period, passenger railmotors operated daily, while mixed goods trains continued to serve the farming communities along the route.

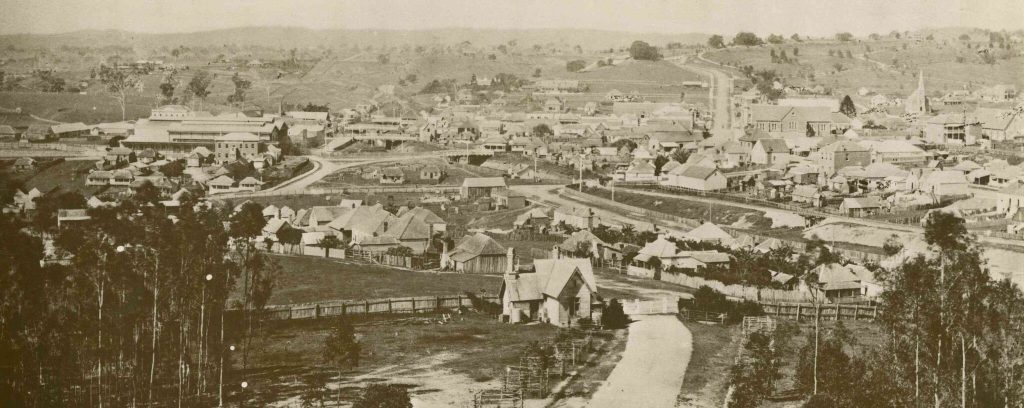

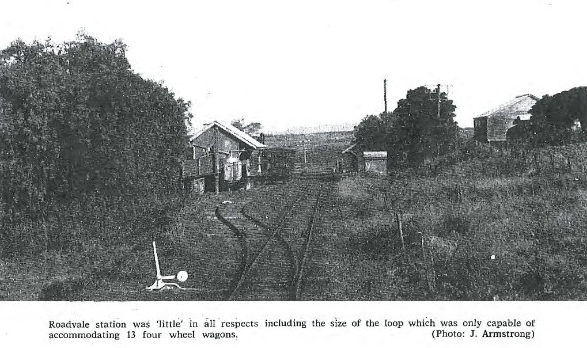

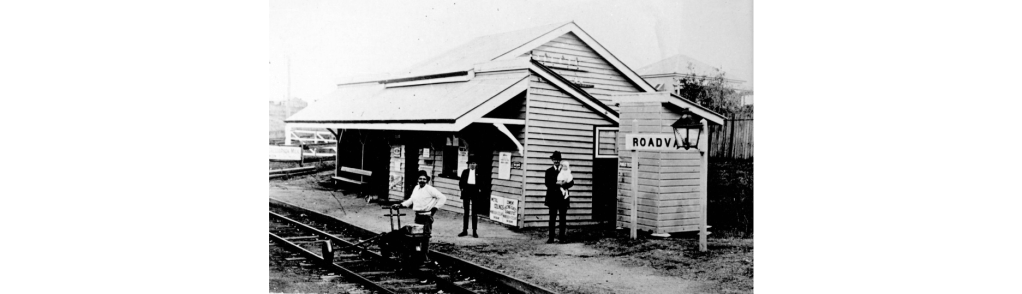

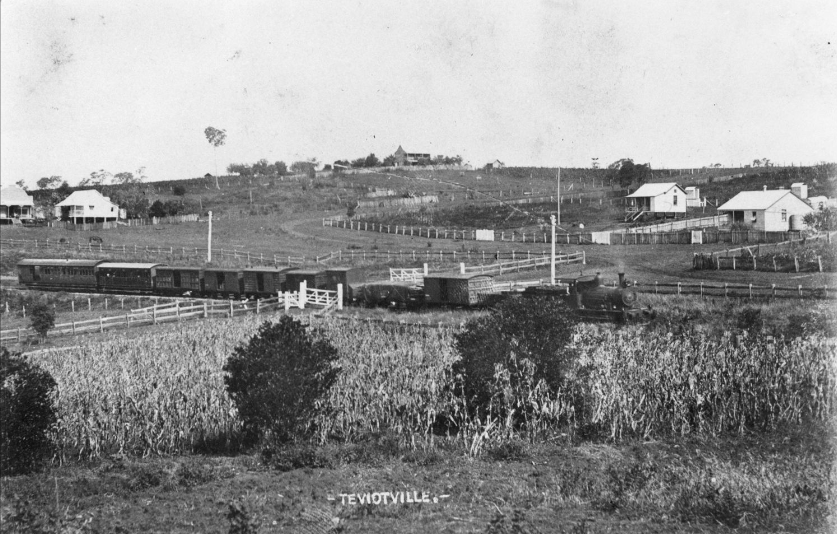

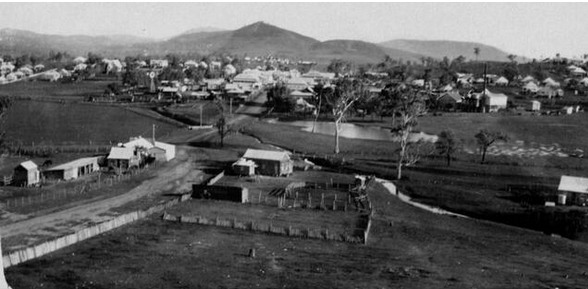

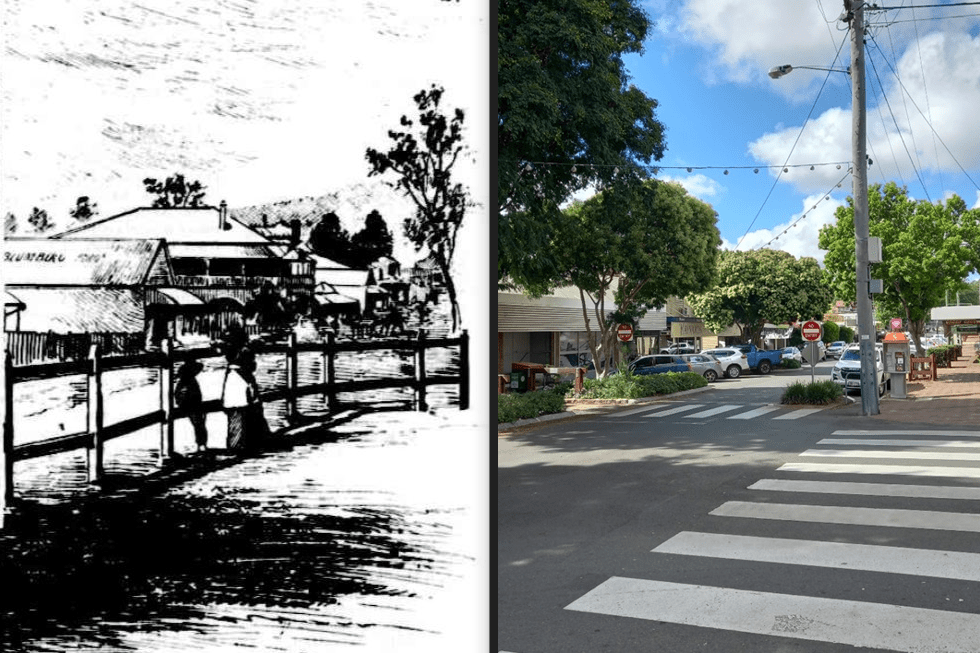

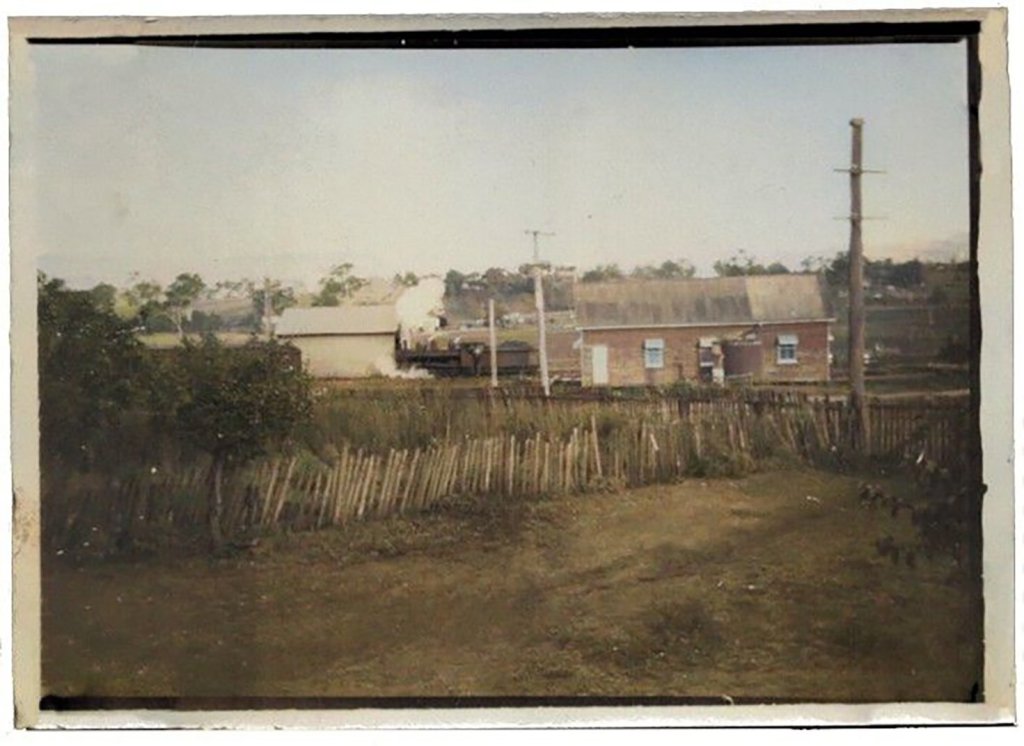

Note station building top left. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

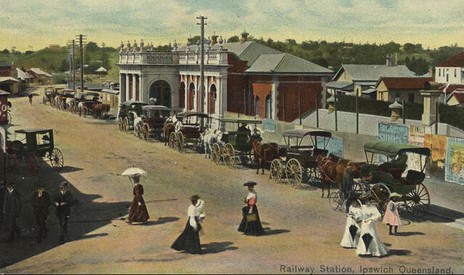

IPSWICH (0 km)

The line begins at Ipswich, the bustling railway hub west of Brisbane. Passengers board amid the clatter of steam engines, shunting wagons, and the smell of coal smoke. The Fassifern branch departs in a southwesterly direction.

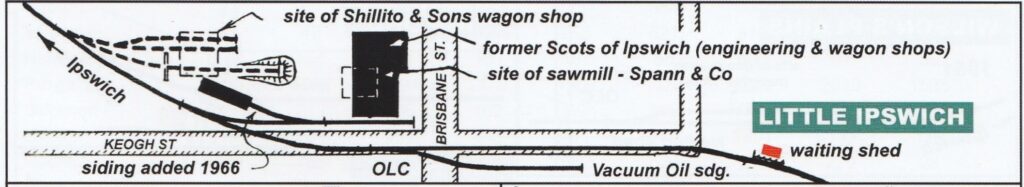

LITTLE IPSWICH (1 km) – An industrial hub and suburban stop, the station served the district’s growing population. Workers and schoolchildren relied on it daily. The area first developed as a crucial transport hub and supply point for the Darling Downs and beyond.

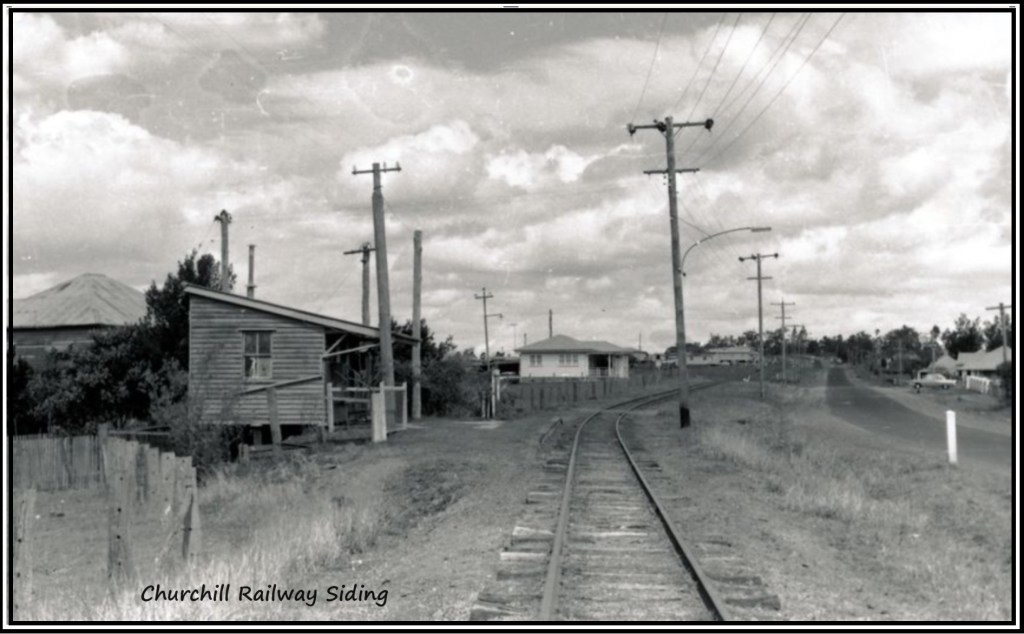

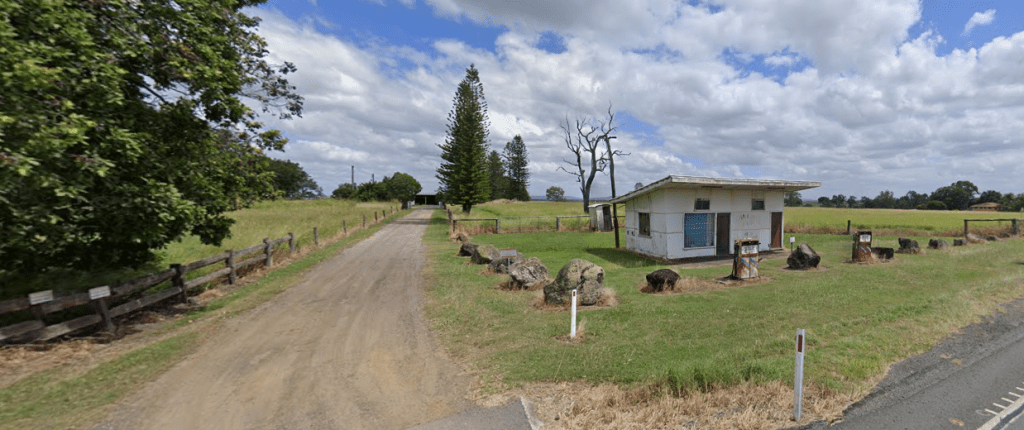

CHURCHILL (3 km) – The area developed around the 1873 Ipswich Showgrounds, and a soap and candle factory was established in 1866. With the opening of the Fassifern railway in 1882, the establishment of a post office in 1892, housing development followed, and the founding of Churchill State School in 1923. The suburb expanded rapidly during the post-WW1 years and continued to grow throughout the early 20th century.

At its heart was a small railway platform in a working-class suburb of Ipswich, primarily used by locals commuting to town, local industry or traveling to nearby farms.

LOAMSIDE (6 km) – Named for the fertile loamy soils of the district. Trains often picked up produce here — vegetables, hay, and dairy cream cans & cotton in the early days.

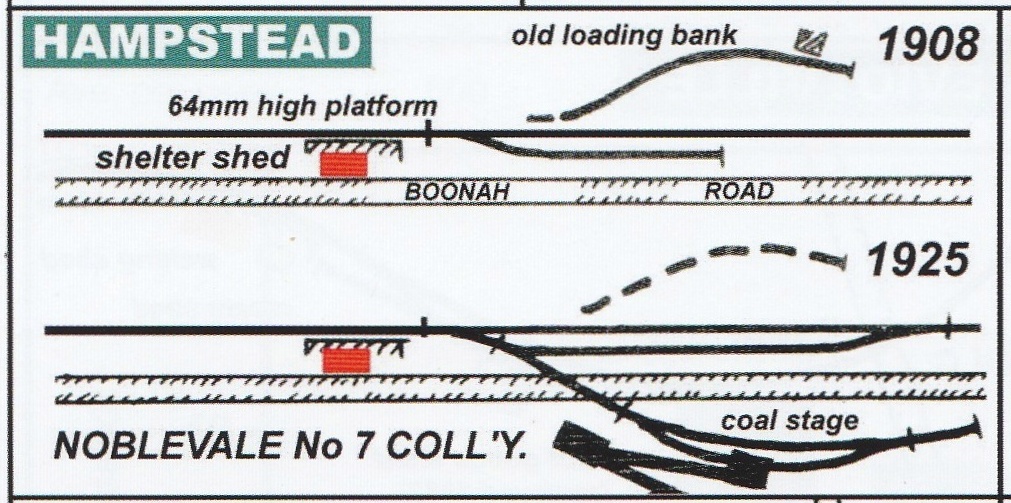

HAMPSTEAD (9 km) – A minor siding, mainly for agricultural traffic. Local farms relied on the train for transporting small goods. Coal was also transported into Ipswich from a nearby colliery in the 1920’s.

PURGA (15 km) – One of the earliest farming districts outside Ipswich, with strong connections to a nearby Aboriginal mission. Dairy and crops were the main traffic here.

GOOLMAN (18 km) – A rural stop at the foot of the Goolman Range. Timber and firewood were loaded here, while travellers enjoyed their first glimpse of the Scenic Rim hills.

HILLSIDE (19 km) Locality station, occasional stops if passengers are on board. In the early years of the railway, cotton & maize were grown & freighted on the trains, with grazing later being more prevalent.

ROCKTON Locality near Peak Crossing

PEAK CROSSING (22 km) – was a lively farming centre with cattle and cream traffic, and also had a large sawmill serviced by the railways in the early days. The town clustered around the station, complete with hotels and shops.

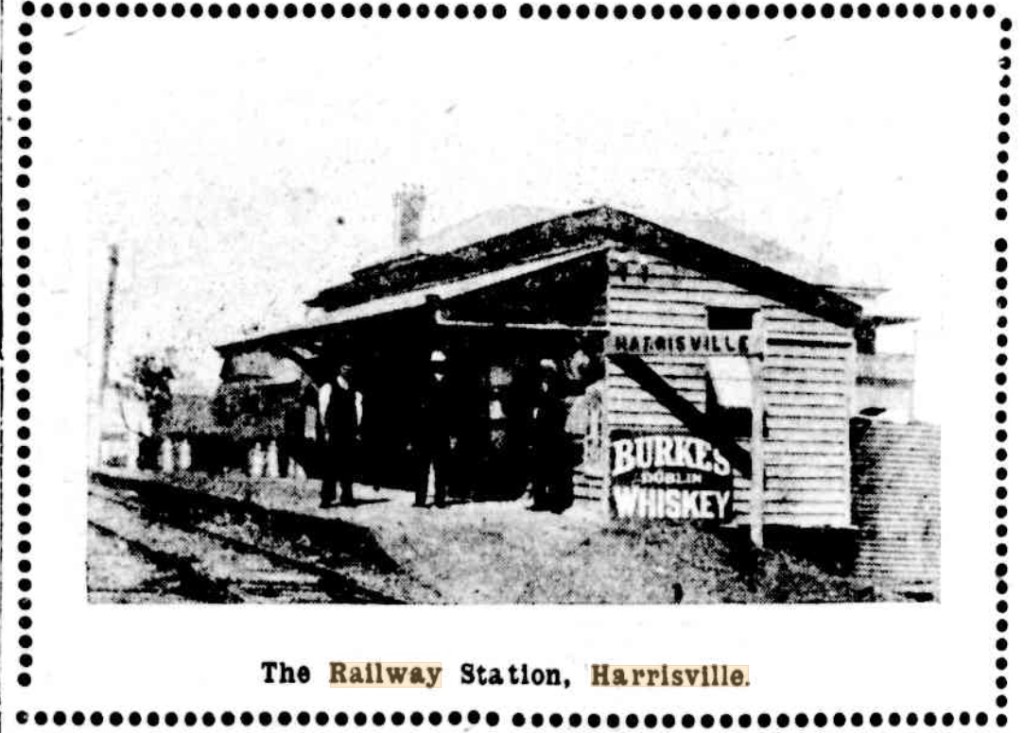

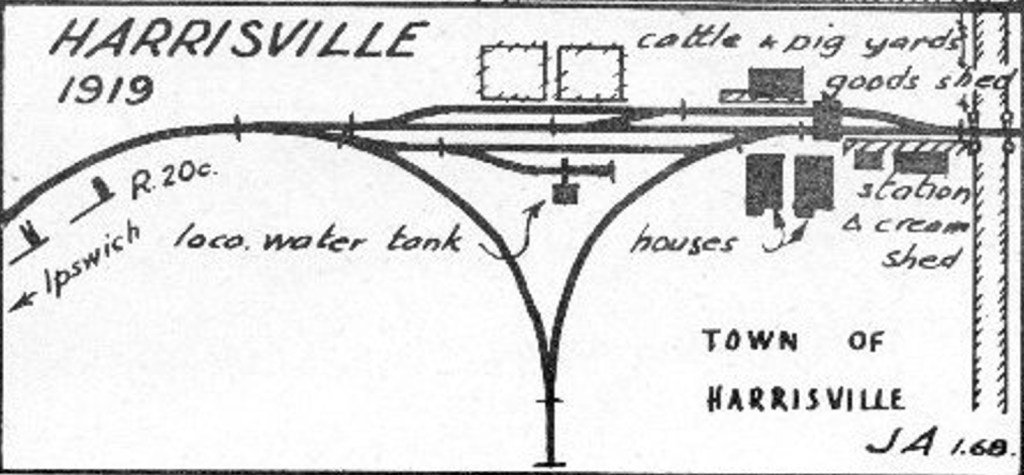

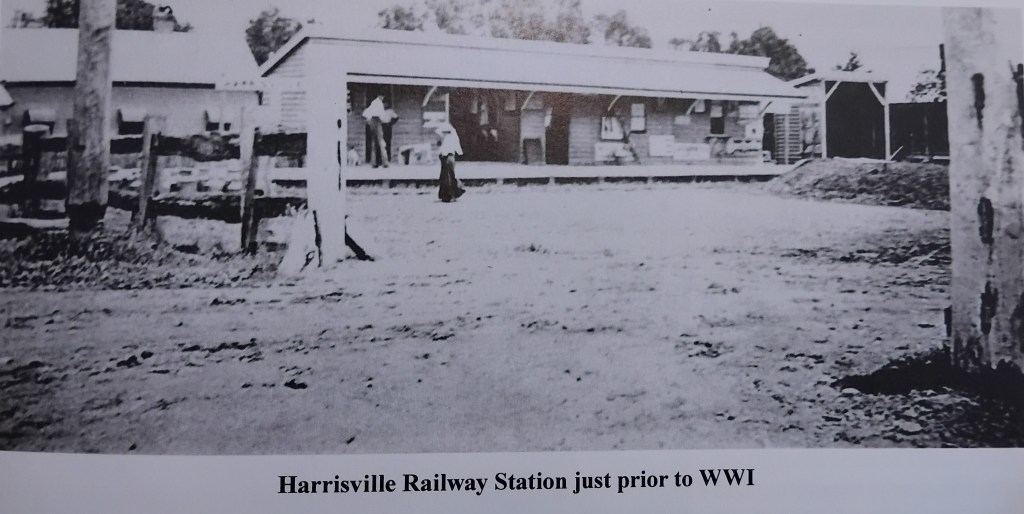

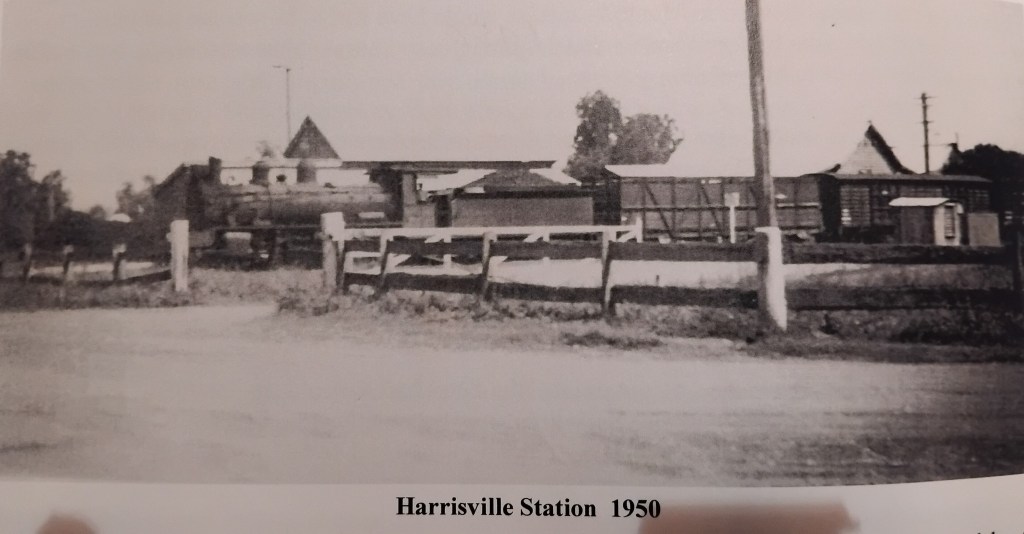

HARRISVILLE (28 km) – One of the key towns on the line, with a large station yard, goods shed, and stockyards. Cotton was an early crop here, later replaced by dairying and vegetables. Harrisville was the first terminus when the line opened in 1882.

WILSONS PLAINS (33 km) – A small rural siding serving local farms, mostly for cream, hay, and small goods. Named after the first owners of the Mt Flinders station property.

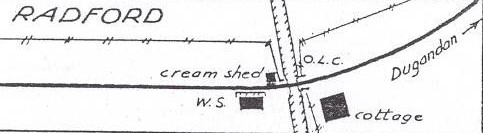

RADFORD (36 km) – A modest station for the surrounding settlement, handling mainly timber and cream traffic.

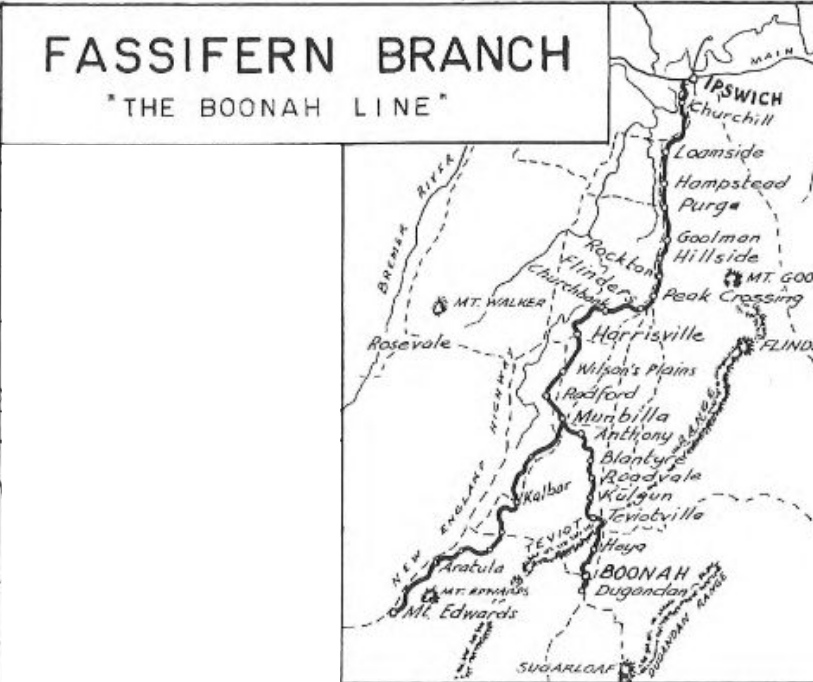

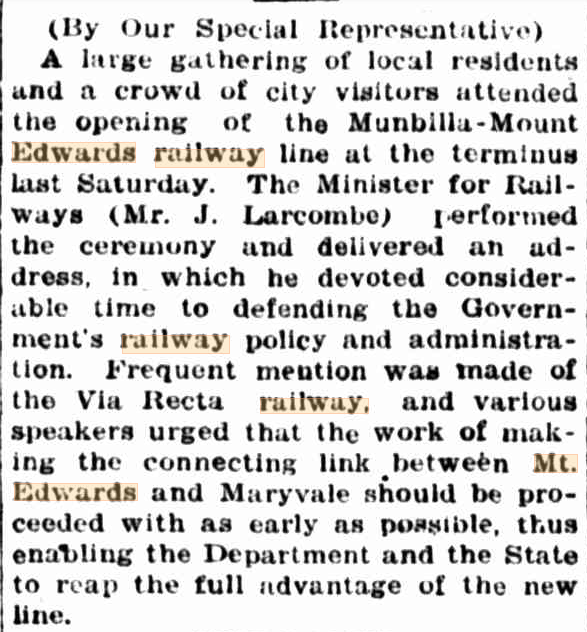

MUNBILLA (38 km) – Munbilla was a junction station from 1887, when the Mount Edwards branch line diverged here. Munbilla became an important hub for livestock and goods traffic. An extension branch line was opened to Kalbar on 17 April 1917 & then extended further to Mt Edwards & opened on 7 October 1922.

MUNBILLA JUNCTION – MT EDWARDS BRANCH LINE – Kalbar – Morwincha – Aratula – Mt Edwards

WARAPERTA (43 km) – about 7 km up from the junction with the Dugandan line. Small settlement serving the local farms

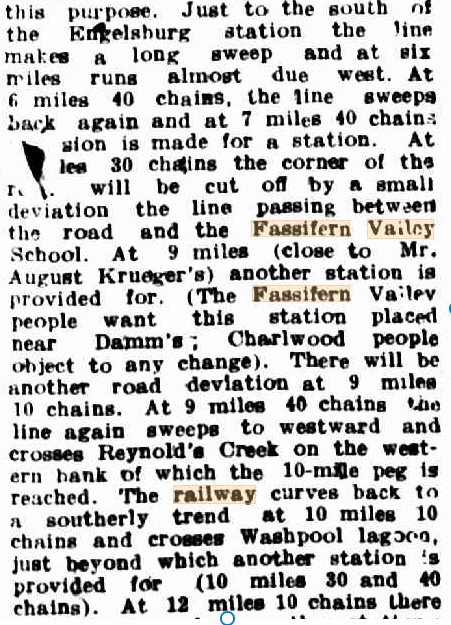

KALBAR (47 km) – Formerly Englesburg. The rail extension to Kalbar was originally constructed to serve the Fassifern Valley, but was also intended to form part of the Via Recta (Latin for “straight route”) rail project, which was planned to cross the Main Range to Maryvale and ultimately reach Wallangarra on the Queensland border, linking with the interstate standard-gauge New South Wales line.

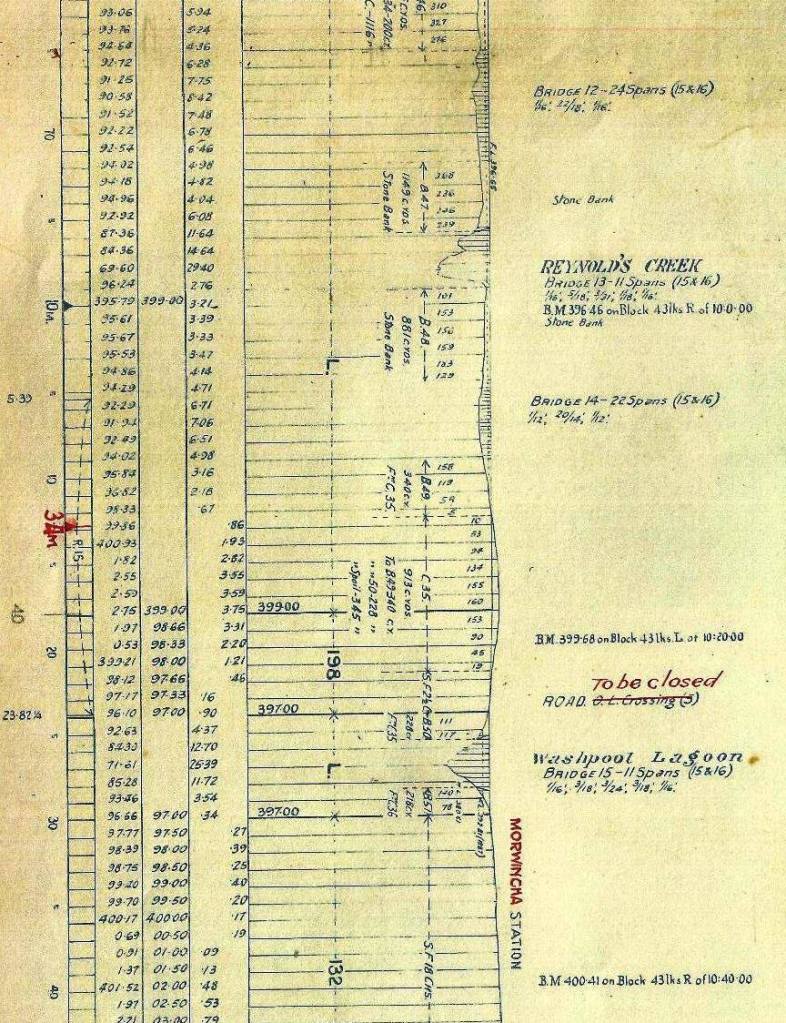

Queensland Railways intended the Munbilla junction to Mt Edwards section of the line to be built with heavier infrastructure—stronger track and higher-capacity bridges—to handle more frequent and heavier freight traffic. This was in anticipation of the Via Recta project, which aimed to maximize Queensland’s capacity for hauling goods in competition with New South Wales.

Side note – However, the somewhat short-sighted approach of governments and authorities at the time (and, arguably, still today) meant that the earlier, lighter-duty track rails and bridges—along with the acute turning radii from Ipswich through Munbilla Junction to Boonah, marked by steep gradients, tight curves, and lightweight creek-crossing bridges—would have required extensive upgrades to meet the standards of the Via Recta project. Many of the culverts, bridges and sections of the rail corridor leading into Munbilla from Ipswich would even have needed complete re-engineering & possible relocation.

When the construction started on the line, commencing from Ipswich, the earthworks had been carried out on only a minimal scale, with most bridges little more than culverts or simple flood openings. Tight-radius deviations were the norm, while significant earthworks were virtually absent after the first three miles of construction. Instead, the roadbed largely followed the natural rolling contours of the countryside to reduce costs. Small embankments and flood openings carried the rails across gullies, keeping expenses to a minimum but compromising long-term durability. I can certainly vouch for that description of the construction. When I travelled the line from about 1959, through to its closure, the old red railmotors were certainly doing a lot of rocking & rolling along the train line to & from Boonah.

In the end, the Via Recta project was never completed and ultimately abandoned.

Kalbar itself was in the heart of a significant agricultural district, known for its produce, beef, and dairy farming.

FASSIFERN VALLEY (53 km) – a small locality station further up into the valley. My ancestors—the Mullers, Krugers, and Kublers—owned farms surrounding this rail station. The Fassifern Valley boasted some of the richest soil in South East Queensland, where the district cultivated a diverse range of vegetable crops in its fertile land.

WARUMKARIE (50 km) – a small locality station further up into the valley.

The farmers and residents of Boonah and the Fassifern Valley were in urgent need of a reliable transport network to deliver their produce to the markets of Ipswich and Brisbane. By contrast, the Lockyer Valley and the towns west of Toowoomba had already gained a significant advantage, with the main western rail line connecting them to the capital, two decades earlier.

The construction of the Fassifern line helped local farmers regain competitiveness by enabling them to supply dairy, livestock, vegetables, and grain from the valley’s fertile soil to Ipswich and Brisbane more quickly and reliably, while ensuring their products remained fresh.

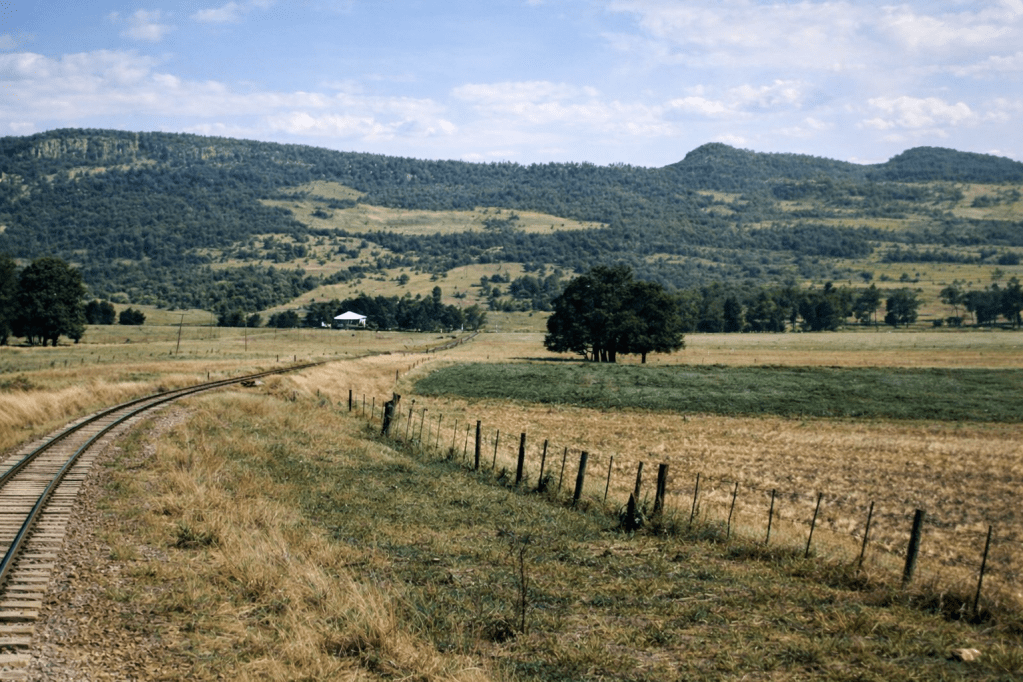

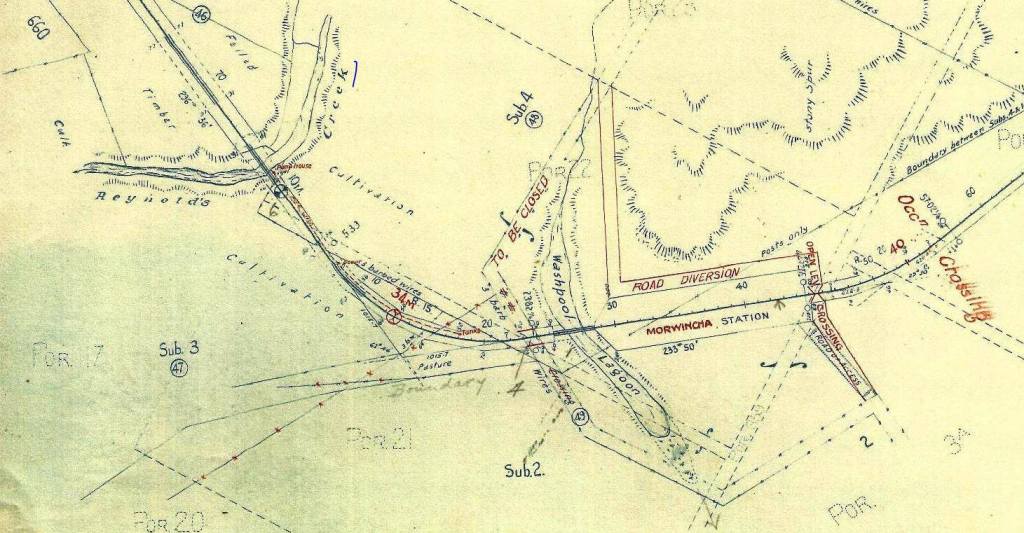

MORWINCHA (55 km) – Rural locality serving the farming community in the area.

ARATULA (58 km) – At the base of the main range, serving mainly the grazing properties in the community. The construction of the railway line was a major factor in the development of Aratula, fostering agriculture and settlement in the Scenic Rim region

MT EDWARDS (64 km) – Terminus. The station was envisioned as part of a route to Warwick but the project was halted by the Great Depression, changes in government, and opposition from Toowoomba.

It was an intriguing period in Australia’s transport history—a time marked by overlapping events that would shape the nation’s future & the decision to go ahead with Via Recta. Entering the 1920s, Australia was still in recovery mode, following the end of WW1, suffering labor shortages & was on the brink of a severe worldwide economic depression. There was intense lobbying from Toowoomba, with local interests determined to secure the major freight connection through their region.

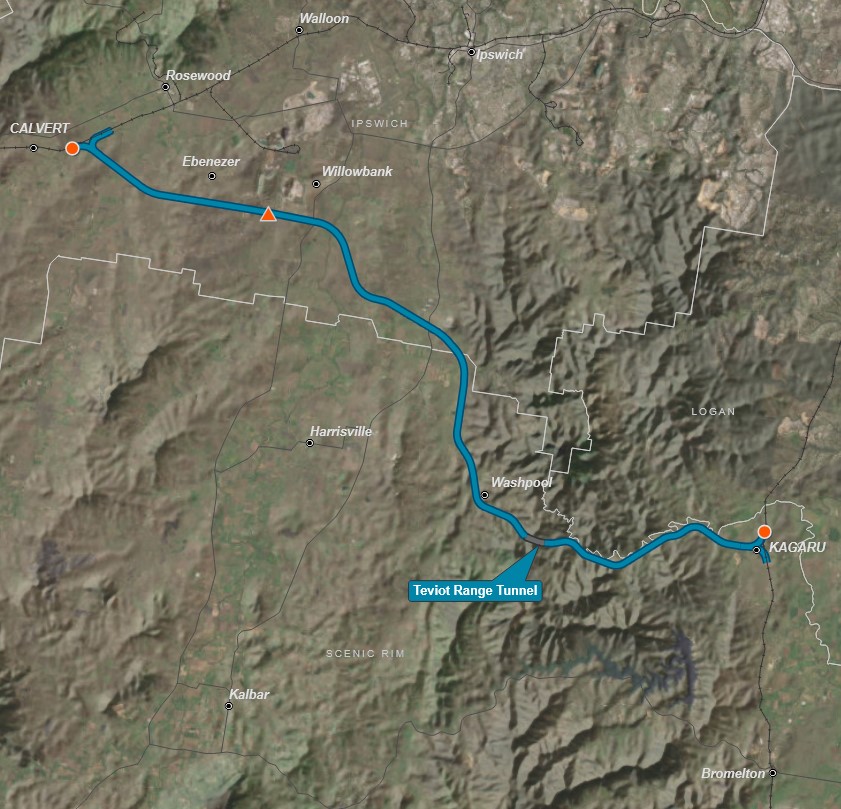

Fast forward to 2025, and the Inland Rail project is well underway. Designed to connect Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane through an extensive regional freight network, the project aims to streamline the transfer of goods between the three eastern capital ports. The final Queensland section, extending from the Darling Downs over the range into Brisbane, is now in the final stages of planning.

A century ago, the proposed Via Recta route included the stations of Mt Edwards and Maryvale—just 30 kilometers apart as the crow flies. Yet, as so often happens, government inefficiency, political disputes (particularly with Toowoomba, situated further north), and the onset of the Great Depression ultimately doomed the project.

Now, a hundred years later, the multi-billion-dollar Inland Rail corridor is roughly two-thirds of the way to Queensland. Could the Via Recta section of that original interstate rail proposal have become part of Inland Rail if it had been completed a century ago? Perhaps! Particularly, if there was already an existing corridor of rail track in place to build upon and expand. Over the past hundred years, advances in rail technology—more powerful locomotives, higher speeds, two-kilometer-long double-stack container trains, heavier track capacities, improved rolling stock, straighter rail corridors, advanced tunnel-boring machinery, reduced manpower requirements, and sophisticated signaling systems—have revolutionized the industry.

The way governments at all levels—local, state, and federal—operate could mean that, if not for the issues of the time, the Via Recta project might have developed into something much larger, rather than being consigned to the pages of history.

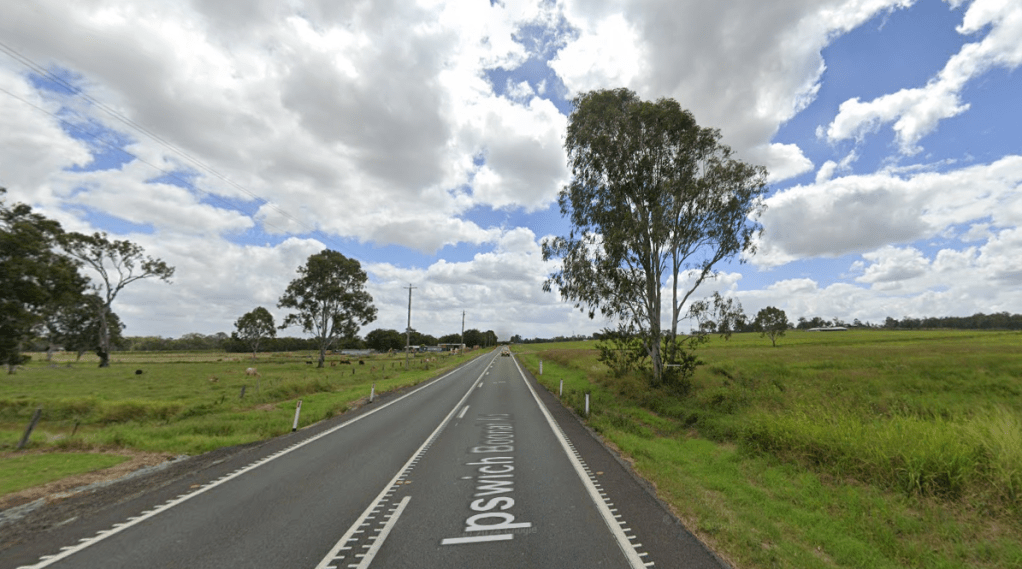

Instead, Inland Rail will traverse the range via a new tunnel from Toowoomba to Helidon, before continuing cross-country through Calvert, where it will connect to the existing interstate rail line at Kagaru. The route will cross Boonah–Ipswich Road near Peak Crossing, then follow the upgraded standard-gauge line to the Acacia Ridge container terminal and onward to the Port of Brisbane.

Still, one can’t help but wonder how different things might have been had the project come to fruition all those years ago.

Apologies for veering into Inland Rail territory, but the Via Recta project was a fascinating and controversial tale, one that, if realized, might have dramatically transformed and reshaped Australia’s rail transport network & made a significant difference to life as we know it in the Fassifern Valley.

In some ways, we truly dodged a bullet. Thankfully, those massive freight trains won’t be thundering through our beautiful Fassifern Valley anytime soon.

We’ll reconnect to our journey to Boonah/Dugandan from Munbilla Station.

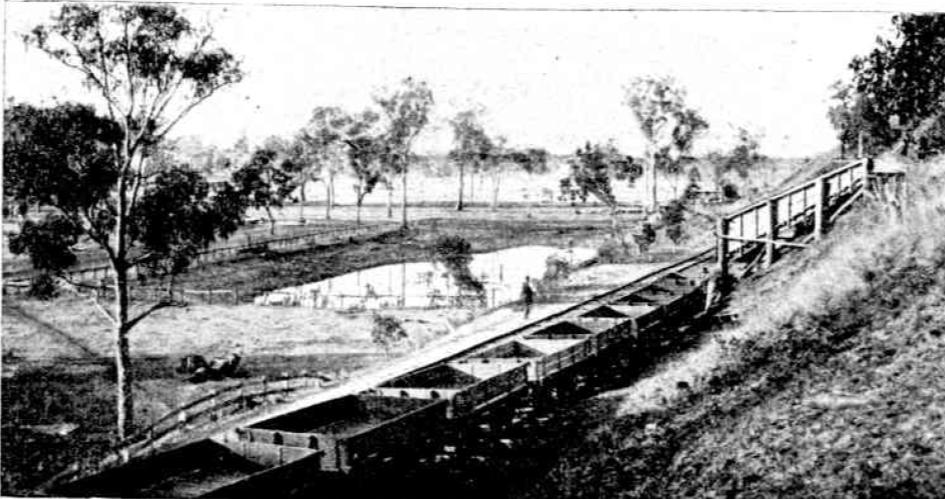

BOONAH/DUGANDAN LINE – FROM MUNBILLA JUNCTION

ANTHONY (41 km) – A small farming siding where the train might stop briefly to collect milk cans or set down passengers. In the early days of the railway line, after leaving Anthony, the train would pass a mile beyond this point, across gum and ironbark ridges, before entering the Dugandan Scrub—a vast expanse of dense brigalow brush stretching over low hills and valleys for miles in every direction. It was a splendid tract of rich agricultural land, every acre selected, much of it cleared and cultivated.

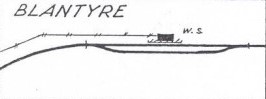

BLANTYRE (43 km) – Another rural stop, surrounded by rolling countryside with maize fields and dairy herds visible from the carriage windows.

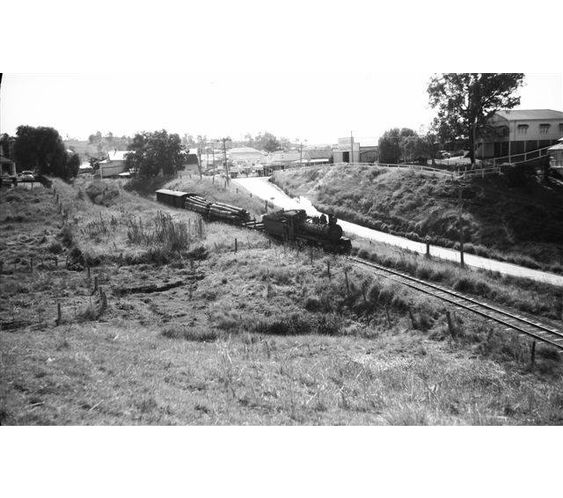

Interestingly, the land behind the train—appearing to be ravaged by bushfire—may have been inadvertently ignited by a passing steam locomotive. Such incidents were common in the era of coal-fired steam trains, when escaping sparks could easily set the dry grass along the tracks alight.

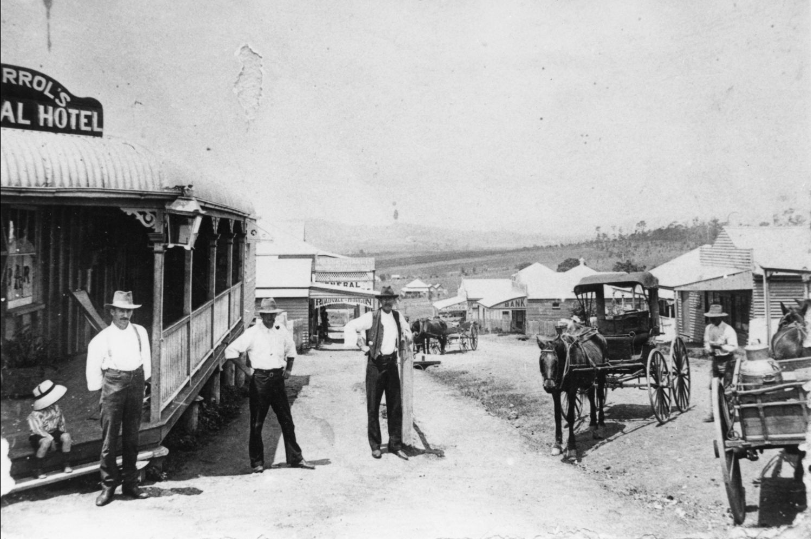

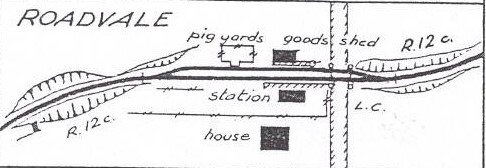

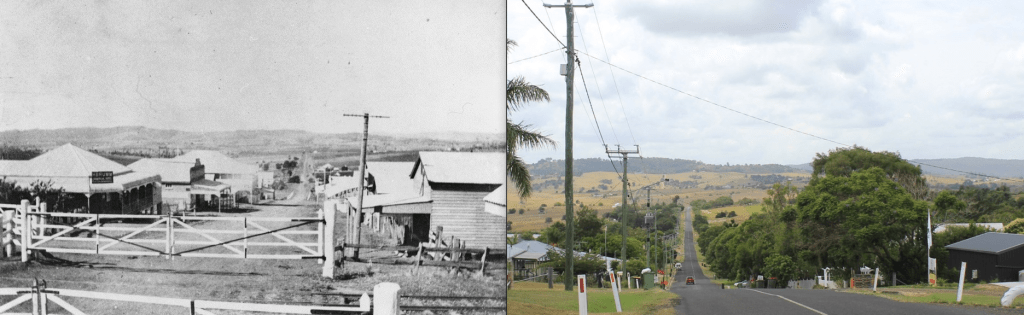

ROADVALE (46 km) – A busier village station with a platform and shelter. Roadvale supported a township with shops and churches, and the station handled daily produce.

KULGAN (48 km) – A tiny halt serving surrounding farms, mainly for cream and produce.

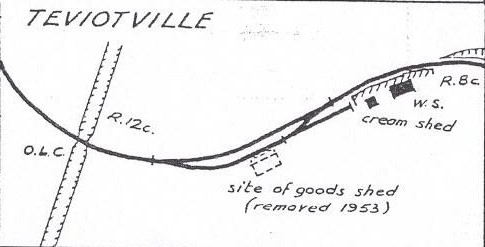

TEVIOTVILLE (50 km) – Close to Teviot Brook, this siding served local farmers. Not a township, but important for produce shipments.

HOYA (51 km) – A very small stop for the farming district north of Boonah, primarily for milk and cream traffic.

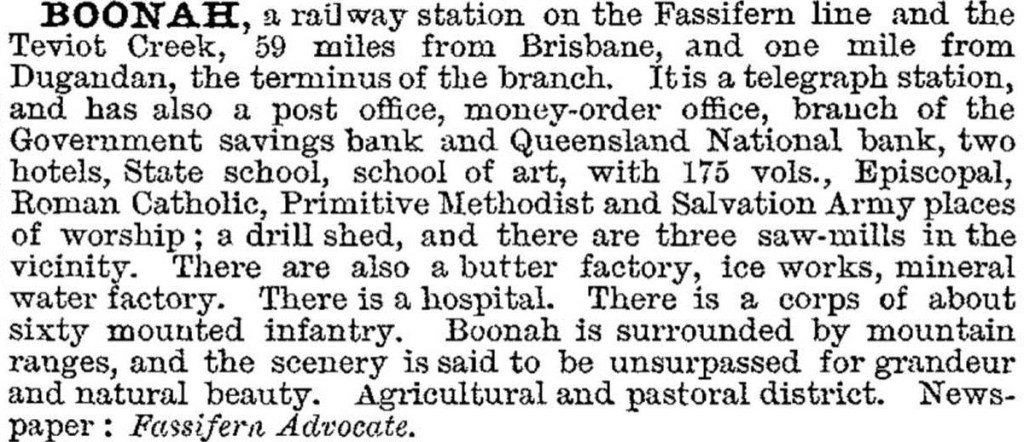

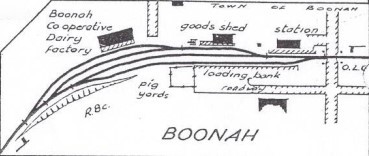

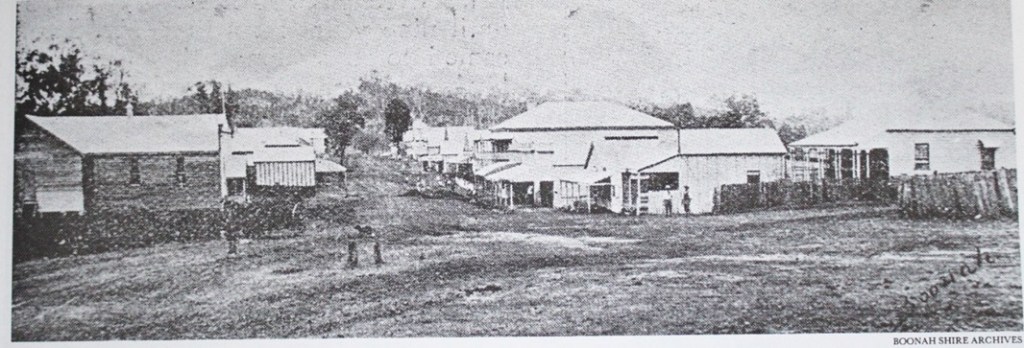

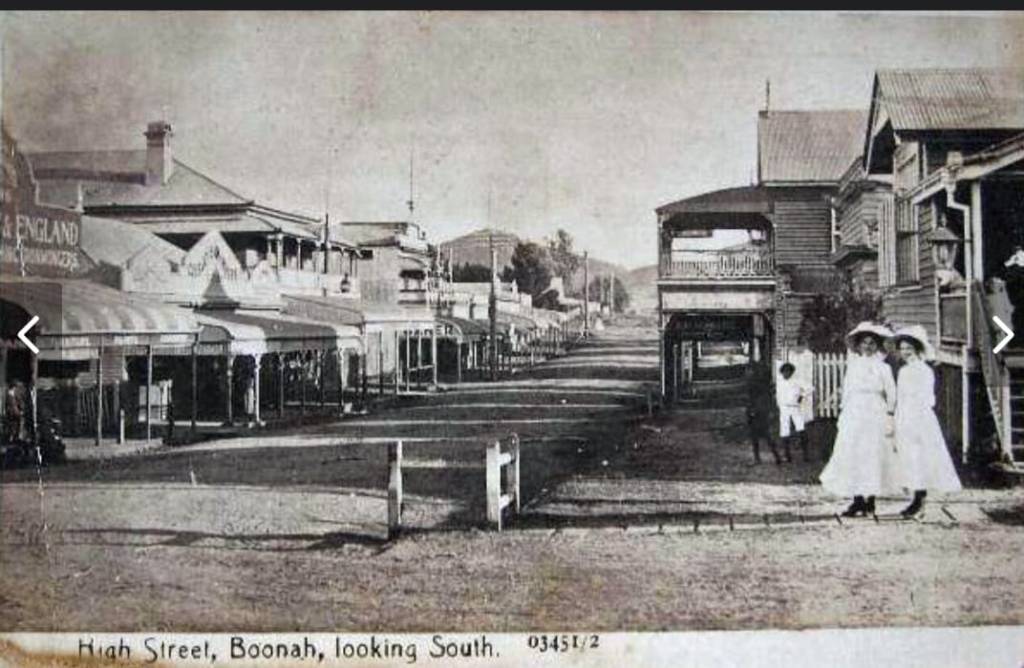

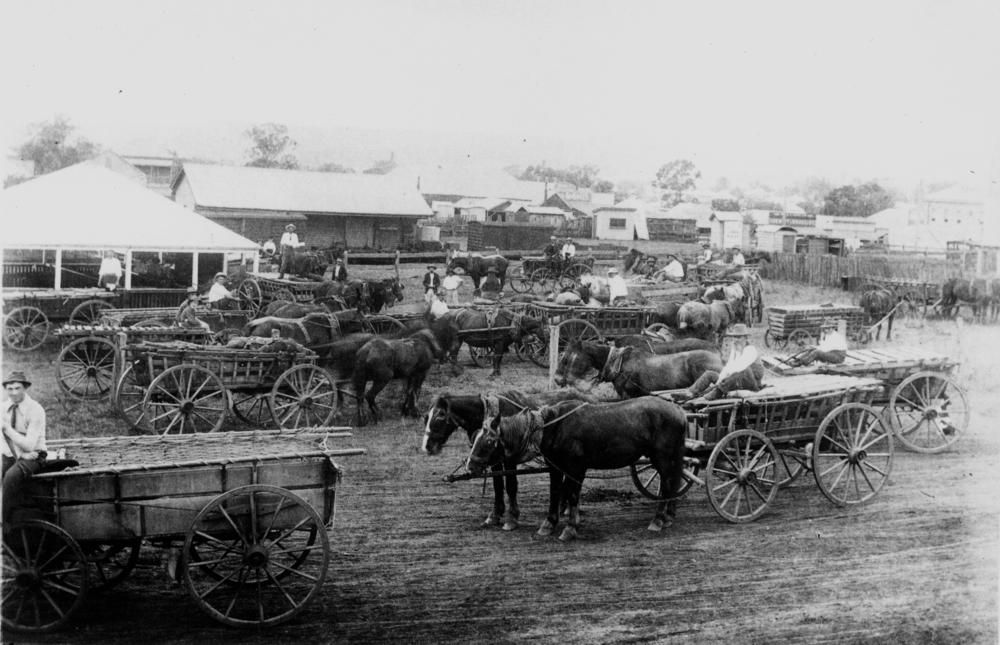

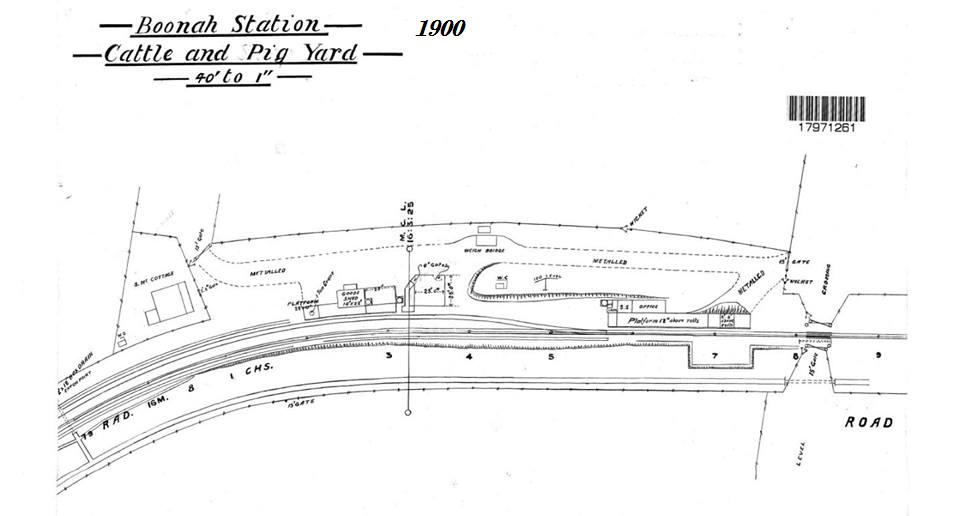

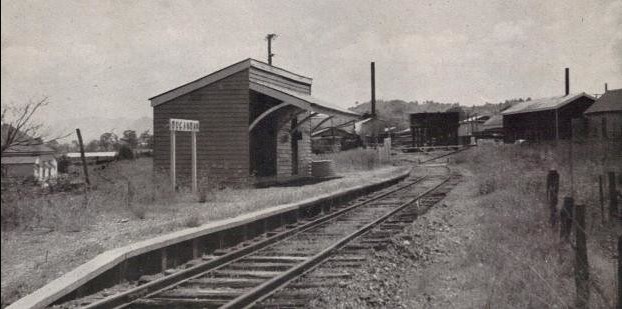

BOONAH (52 km) – The main town of the district. By the early 1900s, Boonah had surpassed Harrisville in importance. Its larger station yard handled timber, livestock, grain, vegetables, and cream. Passengers alighted here to shop, attend markets, or travel further into the mountains.

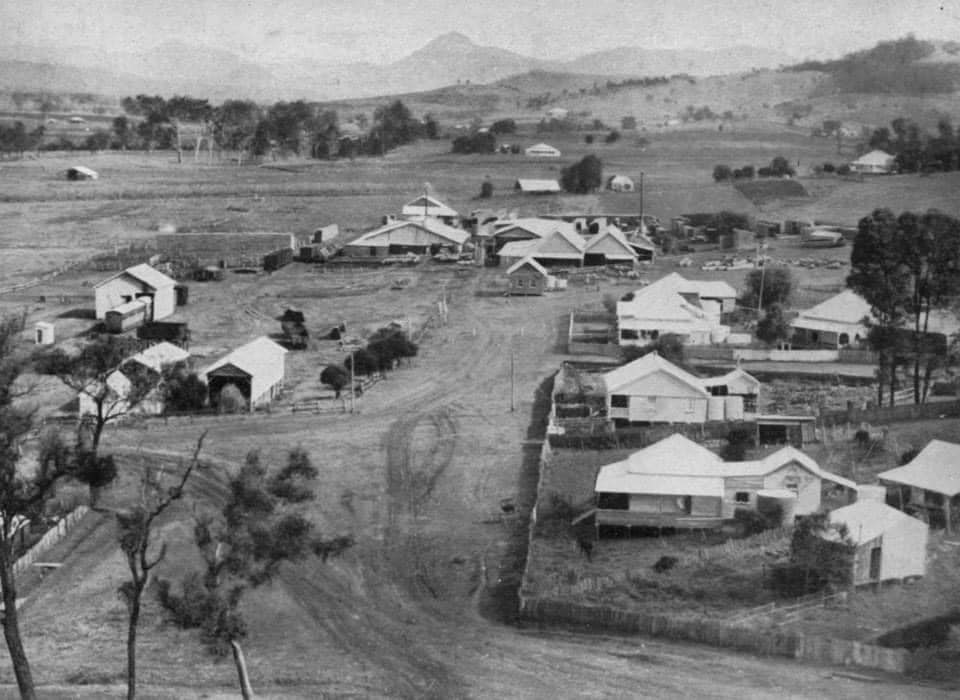

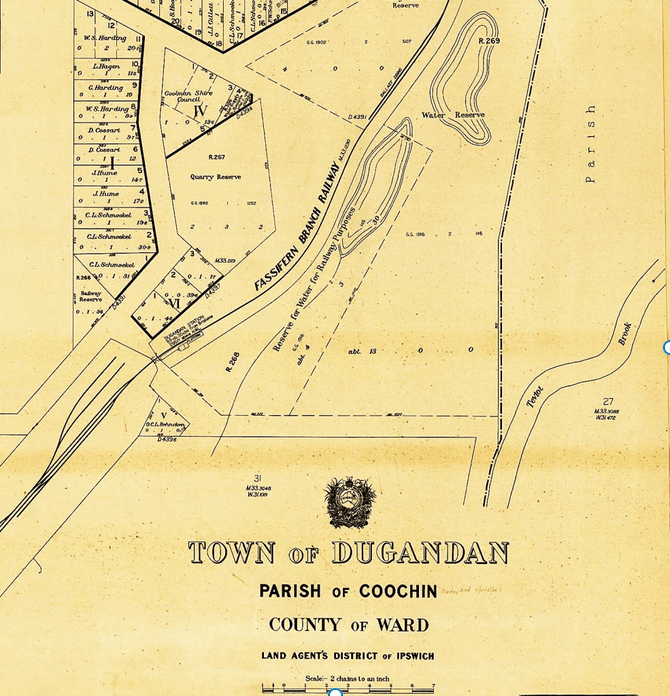

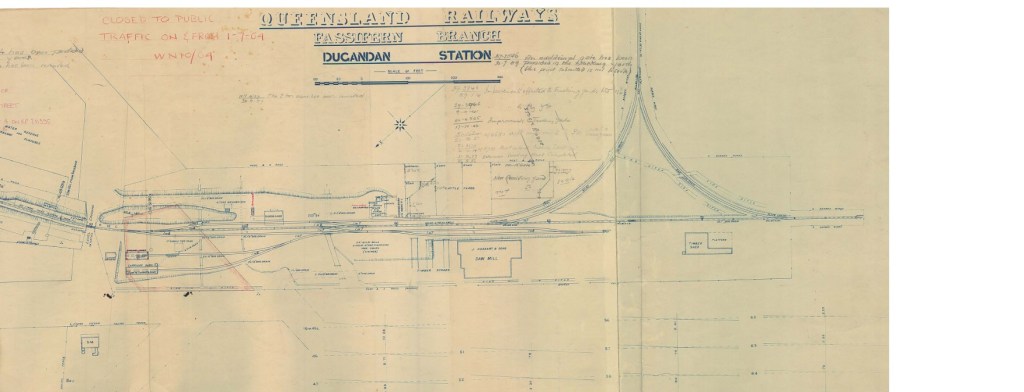

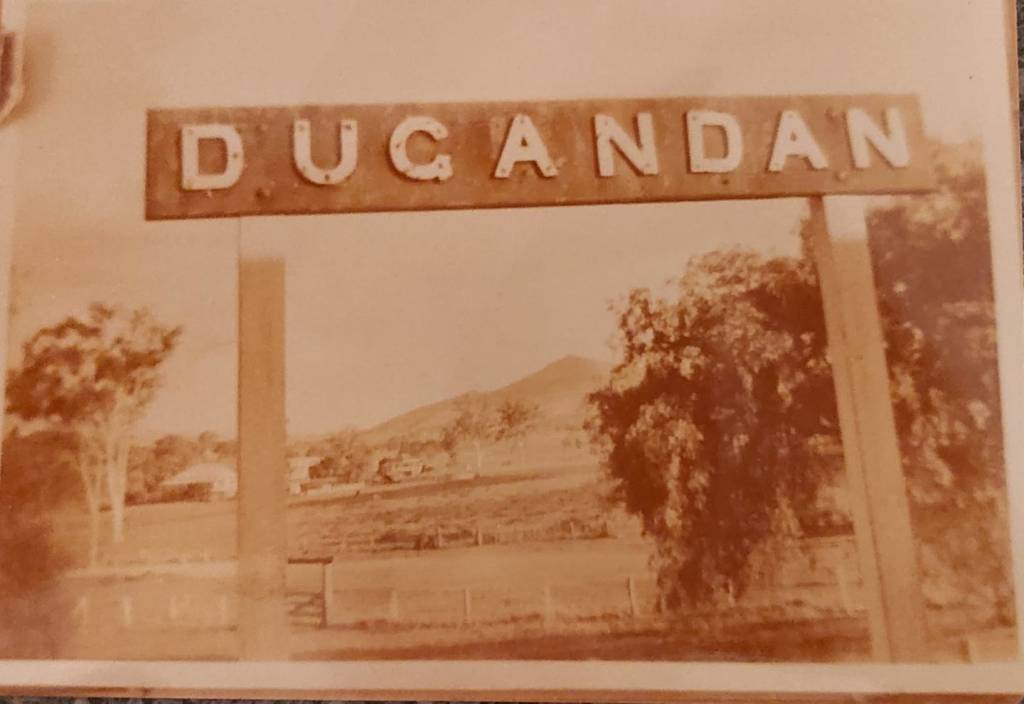

DUGANDAN (54 km) — Terminus – The line ended at Dugandan, near the Dugandan Hotel. It had goods sheds, sawmills, and stockyards, keeping the station busy. From here, bullock drays and coaches carried goods further south toward Mt Alford and Maroon.

🌄 The Journey in Summary

From the bustle of Ipswich, through fertile farmland and quiet rural sidings, past dairies and cream cans waiting on platforms, to the thriving towns of Harrisville, Boonah, and finally Dugandan — this line was a lifeline for farmers and communities in the Fassifern Valley until its closure in 1964.

The trains were usually mixed, carrying both passengers and freight, and speeds were slow — often under 30 km/h. Along the way, travellers would see:

- Rolling farmland with cotton, maize, and dairying paddocks.

- Small German farming settlements.

- Teviot Brook and the surrounding Scenic Rim mountains.

By the time you reached Dugandan, the Dugandan Hotel was only a short walk away, welcoming thirsty travellers with a well-earned drink. 🍺

From my perspective as a child travelling to Boonah with my parents, we often went by train — especially Dad and I. Visiting relatives meant travelling from our home in suburban southside Brisbane to Boonah, and it certainly wasn’t a trip you made if you were in a hurry. Current trip distance – 90km. Usually done in just over an hour.

I can still remember Dad and I leaving home around 8 a.m. on a Saturday morning, catching a cab to Corinda Station, then boarding the suburban train to Ipswich, stopping at every station along the way. The old Boonah railmotor would depart Ipswich at about 10 a.m. The journey to Boonah usually took around three hours, with frequent stops to drop off and pick up passengers.

It was a more relaxed era in Queensland’s history, when people seemed far more laid back about life in general — and even more so the further you travelled out of Brisbane and into the country. Although a timetable existed, there was no strict enforcement to ensure the railmotor ran on time.

Being a Boonah local, Dad knew many of the other passengers. At Harrisville, the railmotor often stopped long enough for Dad and the driver to duck over to the pub for a beer and a pie. Nobody on the train seemed concerned about the extended stop — in fact, a few passengers often joined them. Life really was easier going back then.

To give you an idea of how casual things were, I recall one Sunday afternoon when Dad and I were travelling home from Boonah. Somewhere between Peak Crossing and Ipswich, where the line runs close to the Ipswich–Boonah road, Dad spotted one of the Boonah locals — the town electrician — driving towards Ipswich in his Holden panel van. Because Dad knew him well (he had also worked as an electrician and telephone linesman in his younger days around Boonah and southeast Queensland), he leaned out of the carriage window, waved, and called out.

To my amazement, the driver of the railmotor asked if Dad wanted him to stop so we could continue the journey with his friend. And so he did. The train stopped in the middle of nowhere, we got off, and caught a lift to Brisbane in the back of Dad’s mate’s van. I couldn’t imagine Queensland Rail staff doing anything like that today.

On another couple of occasions, we missed the Sunday afternoon Boonah–Ipswich railmotor and had to catch the later mixed goods train that departed around 4 p.m. That trip dragged on until nearly 11 p.m., stopping constantly to shunt and load goods along the way. Dad and I rode in the guard’s van at the back of the train — long, slow trips I’ll never forget, although the rail journeys were always interesting & exciting for a kid.

The rail line and its train services were finally closed in 1964, a casualty of progress. In its early years, it offered a far more reliable option than the rough roads of the time, which were often impassable for days due to bad weather, with horses and carts easily getting bogged.

Many of the earlier inhabitants of Boonah travelled there originally on the trains, my ancestors being some of them.

The local farmers relied on the trains to get their produce and livestock to markets. The many local businesses & sawmills utilized the railway to shift goods to & from Boonah to the Brisbane ports for export & to destinations further afield across the state.

Post WW2 & through to the 1960s, however, roads had greatly improved, and road transport proved much faster. Refrigerated road transport could deliver produce direct to markets in Brisbane and Ipswich more quickly, ensuring freshness for consumers. Dairy products such as milk, cream, butter, and cheese, which have short shelf lives, could also be transported directly to processing plants with greater efficiency. Levels of freight started to decrease by the 1950s.

Many older residents of the Fassifern Valley still reminisce about the rail line, and I have done exactly the same in this article. I often read accounts from people mourning the loss of trains across Queensland’s & Australia’s rail networks from decades past. The romance and adventure of historic train travel linger long after the journey ends, unlike modern trains, which lack the same charm and sense of adventure.

The reality is that while these historic services played a vital role in developing and expanding the regions they served, they eventually became obsolete.

Rail lines throughout Queensland—such as the original Southport/Tweed Heads line, the Beaudesert line, the Brisbane Valley line, Hervey Bay, Killarney, and many others—could not compete with faster, more modern forms of transport. Rail required considerable manpower and multiple stages of trans-shipping to move produce from farm to consumer. Goods typically went from the farm gate—by horse and buggy in the early years, later by truck—to the nearest rail station. From there, they were loaded onto wagons, taken by train to a major hub such as Ipswich or Roma Street in Brisbane, and transferred again to other trains bound for the final destinations, across Queensland’s decentralized rail network.

In contrast, modern refrigerated transport collected produce directly from the farm and delivered it straight to the market or retailer. Passenger services also suffered. The old red railmotors & wooden passenger carriages were outdated, barely changing in four decades of use, and the track alignments themselves had seen little improvement. As mentioned earlier, a trip from Brisbane’s southside to Boonah took nearly five hours by rail, compared to just one hour by road today.

There is no doubt that Queensland Rail has improved significantly since the mid-twentieth-century branch closures, particularly with the introduction of freight containerisation and refrigeration. Modern rail alignments, track geometry & route optimisation have also drastically changed for the better. However, these changes came too late to reverse the decline. Privatisation has also influenced the operation of the state rail network—sometimes for the better, and sometimes not.

Long-distance rail freight remains highly viable, particularly for transporting bulk commodities such as coal and other minerals from mines to shipping ports for export, as well as moving containerised freight from modern bulk distribution centres operated by major supermarket chains to their stores across the state. Unfortunately, smaller branch lines are no longer economically viable for these types of freight movements.

When it comes to passenger travel, modern city, urban, and regional rail remains a vital component of urban development. Its efficiency, high capacity, and environmental benefits—particularly when electrified and integrated into a wider transport network—make it indispensable. However, its success depends on strong infrastructure, high utilization rates, and meeting commuter expectations for reliability and frequency. Unfortunately, most of the lines that were closed in the past will not be reconsidered, as they no longer meet these current criteria for viability.

By 1964, when the Boonah/Fassifern line and many others were closed, successive governments had failed to address the growing needs of local populations. Personally, I loved the old train line and still treasure childhood memories of riding the railmotors and steam trains. Yet, these belong to a bygone era, inevitably overtaken by progress.

It is important to consider the historical context. Queensland, declared a state in 1859, was financially constrained from the start. The narrow gauge rail network was built on a shoestring budget, earning it the nickname “the pony railway.” By the mid-twentieth century, with little investment in upgrades, many branch lines had reached the end of the line—both figuratively and literally.

With Australia being geographically vast but sparsely populated, the financial burden of keeping these rail lines operational became excessive. Funding was increasingly redirected toward higher priorities such as education, healthcare (including hospitals and aged care), roads, and essential infrastructure.

It is all well and good to appreciate the nostalgia of keeping these lines running, but the question remains: who is going to pay for it? Should we continue funding an ageing rail line with enormous annual costs for track maintenance and rolling stock, despite limited or declining usage, or should we prioritise maintaining schools, hospitals, roads, and infrastructure that directly support the needs of all, in regional communities?

Private corporations are certainly not rushing to invest in the preservation of old rail lines, as the ongoing and substantial upkeep costs make them economically unviable. Even when a benefactor does step in, such arrangements rarely last. Once it becomes clear that the investment is unsustainable and yields little return, the initial feel-good motivation quickly fades.

The days of the Fassifern branch railway had come to an end.

In compiling this story on the Fassifern rail line, I have been able to access many photographs & records from several different sources, which I would like to acknowledge below.

RAILWAY ARCHAEOLOGY IPSWICH

Lee-ann Keefer, for access to her father – Eric Marggraf’s collection