I’m a family history enthusiast who has conducted extensive research into our family ancestors. I also follow numerous historical record sites and social media groups dedicated to old photos, facts, and stories from the era I grew up in—the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s.

One recurring theme I’ve noticed is the shared belief that certain decades were “the best of times.” Many people claim that during those years, few broke the law, everyone had good manners, respected their elders, trusted the police, believed politicians were honest, and felt safe at night—among other idealized notions. I don’t know what rock these people were hiding under, but this perspective can often be attributed to nostalgia and the tendency to view one’s formative years through rose-colored glasses.

Each generation tends to remember their youth as the best and most progressive time, when life seemed easier and more fulfilling. However, viewing the past through such a lens can be problematic as it often skews real-life perspectives. Faulty memories tend to block out the challenging or unpleasant parts of the past, focusing instead on the good moments while ignoring the hardships.

Every generation has had its share of good times, bad times, wars, peacetime, recessions, and depressions. Yet, many prefer to remember only the positive aspects while selectively forgetting the less favorable times—things like world wars, economic downturns, or widespread corruption among politicians and police. This selective memory distorts our understanding of the past and fosters overly romanticized views of bygone eras.

I grew up in a safe, loving, family-oriented environment—well, maybe “loving” is a stretch. The only person I feared was my big brother, who occasionally beat the crap out of me.

Childhood in our suburban Southside Brisbane environment during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s was memorable. There were a few nearby farms, an unfenced golf course where we dodged flying golf balls, and a creek surrounded by natural bushland for exploration. Public transport was poor, roads were rough, and outdoor toilets were common, but it still felt like a happy, safe place.

School days are often remembered as fun. Side note -For me, I was one of those kids who remained invisible and kept to the background. It was actually quite funny when I attended a school reunion a few years ago—no one could remember me.

However, some teachers were brutal and sadistic—not many, but a few. While there were also brilliant educators, the bad ones stood out for their use of the cane and their sheer cruelty. Blackboard dusters were thrown at students. T-squares were slammed across children’s backs. Some male teachers engaged in selective bullying toward particular students.

In modern times, some people reflect on those years and suggest that such treatment taught them to respect their teachers. Well, good for you—if that gave you some kind of misdirected respect for individuals who, frankly, had no place in the teaching profession at the time.

I’ve often thought that many of the people who believed they gained something from being bullied by teachers—and, in some cases, by fellow students—went on to become some of the unpleasant individuals we encountered in workplaces, leadership roles, and political circles. Back then, such bullying was generally accepted, and perhaps that normalization of cruelty helped shape the toxic behaviours we later saw in positions of authority.

I went to a state school, but from what I’ve heard from friends who attended Catholic schools, the nuns and priests took brutality to another level in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Practically every Catholic parish at one stage had a predatory priest who was moved from one parish to another whenever abuse allegations arose. When scrutiny intensified, the church hierarchy would transfer them elsewhere to avoid consequences. As a result, in modern times, the Church continues to face backlash and turmoil. Many children who suffered abuse in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s are now adults grappling with mental health issues stemming from that trauma.

However, the idea that the “good old days” were better than today is a myth. Would anyone in 2025 genuinely trade all modern conveniences to live back then? I doubt it. In fact, I’d guarantee it. Many might claim they would, but if given the chance, they’d likely rush back to 2025 in their DeLorean after a brief visit.

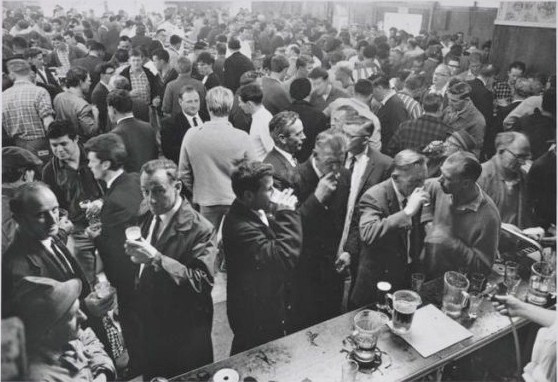

People often view the post-war era selectively, remembering only the good and overlooking the harsher realities. Post–World War II Australia saw a large number of returned servicemen, many of whom were heavy drinkers and smokers—a common consequence of military service. Many of these ex-servicemen and women had witnessed events in the European or Pacific theatres of war that most of us could scarcely imagine. Some had been prisoners of war. Most returned carrying deep psychological trauma.

Later, veterans of the Korean and Vietnam Wars brought their own struggles, including what we now recognize as PTSD. Their experiences further contributed to the rise of alcohol consumption in Australia’s increasingly entrenched drinking culture.

Pubs were everywhere, and owning one was often considered a license to print money. The primary illnesses that caused fatalities among men in the 1950s and 1960s included cardiovascular disease, cancer, and alcohol-related conditions.

In our suburb, two pubs sat within 100 meters of each other, their parking lots overflowing every evening as men stopped for a few beers after work. Back then, all beer was heavy; low-alcohol options didn’t exist. Many of these men were factory workers who felt they deserved a cold drink after a hard day’s labor. Alcohol-driven aggression was fairly commonplace.

In Ipswich, there were approximately forty hotels along the 4-kilometre stretch of the Ipswich CBD area of the 1950s to 1980s. Ipswich was a mining & railway town known for its drinking culture.

Unfortunately, this culture often coincided with domestic violence, a subject rarely discussed at the time. It was sadly accepted that some men were abusive. I knew of several such families in our neighborhood. The police showed little interest in protecting wives and children from abusive husbands. In extreme cases, severely assaulted women could even be institutionalized, often with the complicity of police or doctors. Some families simply disappeared overnight as wives fled with their children to escape toxic relationships.

Another issue linked to alcohol consumption is gambling. Australia has the highest per capita gambling losses in the world. The surge in gambling coincided with the post-war economic boom of the 1950s, during which clubs flourished as large numbers of Australians joined RSL and sporting clubs. These establishments attracted crowds eager to play poker machines and engage in other forms of gambling. The clubs and pubs reaped substantial profits, as did the government through gambling taxes.

Gambling remains a significant issue in Australia, yet governments are hesitant to implement strict measures to curb it due to the substantial revenue they generate from the industry.

As for crime, corruption & public safety, the idea that Brisbane in the post-war years was a utopia where the law was always upheld is nonsense. The police force, for the most part, was deeply corrupt. Not all officers were involved, but the majority were. Honest cops were often transferred to remote outposts, which is why country towns usually had well-respected local policemen. Those officers’ files were marked to prevent them from being promoted to senior ranks. At the time, the QPS had no interest in placing honest policemen in senior or administrative positions.

It’s shocking that many people still live in denial about what truly happened during that era, when corrupt police effectively ran the state. In Brisbane, law enforcement frequently colluded with organized crime, while senior politicians were complicit—often directly benefiting from the widespread corruption.

Figures such as Commissioner Terry Lewis and Detectives Tony Murphy and Glen Hallahan were central protagonists, with the corruption reaching the highest levels of the state government. Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, Police Minister Russ Hinze, and most members of the state cabinet were implicated in these illicit activities. Organized crime was effectively purchasing silence and protection, and the very authorities tasked with upholding the law were willingly complicit.

This was the period in our state’s history when everything came to a head. The Fitzgerald Inquiry exposed the full extent of the corruption, resulting in several politicians and police officers being sent to prison. Unfortunately, many senior officers were permitted to resign—an arguably dignified exit that allowed them to avoid real accountability for their actions. However, the inquiry did lead to the downfall of one of the most powerful figures: Commissioner Terry Lewis, who was sentenced to 14 years in prison, though he was released after serving just 10 and a half years.

Perhaps unsurprisingly—and in a disturbingly covert manner—many of the political ringleaders managed to evade prosecution. It was widely acknowledged that many more individuals should have faced justice.

What’s even more disturbing is that some still attempt to justify this era of corruption, claiming the state was better governed under dishonest politicians and police. This kind of selective revisionism ignores the profound damage that systemic corruption inflicted on public trust, justice, and democratic institutions.

In modern times, politicians still exploit the “crime wave” narrative during elections. In fact, it’s the go-to policy when all else fails. Privately, some politicians hope that serious crimes occur during the run-up to an election, when it is guaranteed to stir up public emotion. However, crime rates in Queensland have steadily decreased over time. While occasional spikes occur, overall crime rates have declined. People often overlook the fact that population growth leads to more reported crimes in absolute terms, but this doesn’t mean crime rates are higher.

Walking around Brisbane after dark today is much safer than it was back then. Those nostalgic for the past would never have dared roam places like Fortitude Valley, South Brisbane, Teneriffe, Spring Hill or around the Eagle Farm wharf areas after dark during the pre- & post-war decades leading up to the 1980s.

If you belonged to a minority group—whether Indigenous, LGBTQ+, disabled, or otherwise marginalized groups—you likely faced poor and sometimes violent treatment at the hands of intolerant individuals in an era when society’s tolerance for such groups was significantly lower. Opportunities and access were severely restricted for disabled people. Public venues and transportation often lacked accommodations, and individuals with disabilities were frequently institutionalized or excluded from mainstream society. Mental health care was virtually nonexistent; people struggling with mental illnesses were often confined to institutions without proper support or understanding. Racism was widespread. Our First Nations people were treated appallingly, and the country still had the infamous White Australia policy enshrined in legislation. Post–World War II European immigrants were often ostracised and subjected to discriminatory treatment by many within the white Anglo-Australian community. Most Australians either ignored the situation or turned a blind eye to it.

The most popular comedians and television shows openly mocked Aboriginal people and migrants—behaviour that was widely accepted at the time and even considered a form of mainstream entertainment.

It shouldn’t come as any great surprise that in modern times, as a society, we wonder why our First Nations people feel so let down by successive governments. We have kicked them from pillar to post since the day the First Fleet arrived.

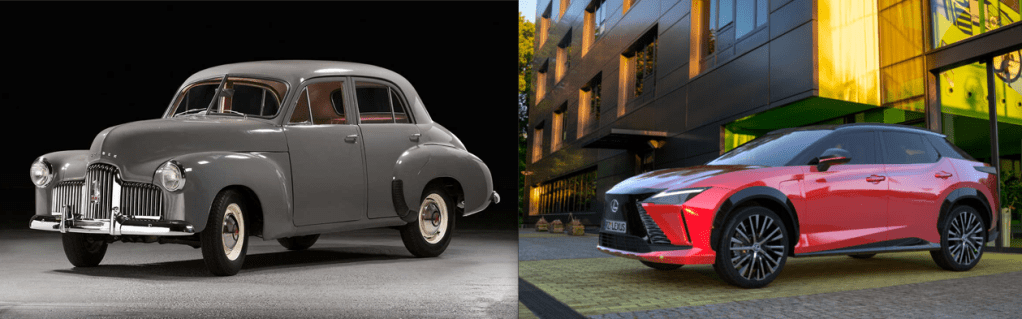

That said, some aspects of those past times were undeniably better. The average family could afford to buy a home and raise children on a single income. Life was simpler, with fewer technological distractions. However, this simplicity also meant fewer choices—whether in consumer goods, cars, or entertainment.

In the immediate post-war era, radio was the primary form of home entertainment. Television arrived in Australia in the late 1950s, revolutionizing suburban life. But it also introduced challenges. Children, once active outdoors, became glued to TV screens.

It is often lamented that many of our historic buildings have been replaced by monolithic concrete structures. However, much of the demolition of beautiful Gothic and Federation-style architecture—as well as the iconic Queenslander homes—occurred in the post-World War II period, continuing through to the end of the 20th century.

During this time, countless magnificent colonial-era structures were torn down and lost—ironically, during an era many now remember fondly. While not everyone who lived through that period had the power to prevent such loss, many were in positions of planning or political influence and could have acted to preserve these irreplaceable buildings.

Of course, in any expanding city, development is inevitable, and not everything could have been saved. Still, as a state, Queensland developed a reputation for readily demolishing heritage buildings and replacing them with concrete monoliths. We only have ourselves to blame.

What makes this more ironic is that the same period, viewed through those nostalgic rose-coloured glasses—was when the destruction occurred. Many of those who now lament the loss were in positions to act but chose not to. Some even conveniently forget that they had the power to vote out incompetent leaders and urban planners at the time.

The era of the Bjelke-Petersen government in Queensland saw the removal of a vast number of beautiful historic buildings. Despite this, his government was repeatedly re-elected with large majorities in every election for nearly two decades.

Road safety is another area where significant progress has been made. In 1952, there were 2052 road deaths in Australia. This number increased to 3164 in 1965 and peaked at 3583 in 1976. Since then, road fatalities have consistently declined, with 1291 deaths recorded across the country in 2024.

Improvements in car design, road construction, and safety measures have been major contributors to this progress. However, any number of fatalities is still too many. The “idiot factor” on our roads remains a persistent issue. As long as people continue to drive under the influence of drugs and alcohol or dangerously exceed speed limits, road tolls will remain a tragic reality.

Education has seen massive improvements over the years. I was born in 1954. When my generation left school to enter the workforce or attend university, we knew practically nothing about life in the real world. These days, however, children are much more knowledgeable, thanks to significant advancements in the education system, from kindergarten through to high school and tertiary education.

Although the advent of the internet has introduced some negative aspects, it has also enabled children to become far more informed than we were at their age. They are more aware of the world, have access to an unprecedented amount of information, and are equipped with the tools to excel in their jobs and careers—far beyond what young adults of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s could achieve.

Kids are still kids, and they continue to need guidance and mentorship. However, with the improvements in the education system and the ability to harness knowledge, they are in a much better position than children of the past.

Advancements in healthcare and treatments for life-threatening illnesses have significantly improved the quality and longevity of life for many Australians. Improved health education and advancements in diagnostic tools have played a crucial role in these achievements.

So, after all things considered… do you really want to return to those “good old days”?

After all is said and done, there’s no harm in reminiscing about days gone by. For some older people, it can be comforting to reflect on their cherished memories—their childhood, their schooldays, their first job, their first love, or raising their kids in the Brisbane of the past. Nostalgia can be a beautiful thing. However, as the banner at the top of the article says, I firmly believe that our best days are still ahead of us.

Sure, there are certainly things that could have been done better. Development and infrastructure have always been areas of debate and discussion when comparing different eras. For example, Brisbane should not have dismantled its excellent public tram network. The demolition of many of our historic heritage buildings is another highly contentious issue, alongside other decisions that, in hindsight, seem questionable.

From a global perspective, history has never been short of authoritarian figures. Since before the 1940s, we’ve seen the rise of leaders like Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Pol Pot—through to more recent figures such as Putin and Trump—who have inflicted damaging politics and policies on their own populations and, in many cases, the wider world.

Sadly, poor leadership and governance is a problem that never seems to go away.

However, I genuinely believe that life today is significantly better than it was back then.

If you prefer to live in the past, that’s your choice. As for me, I’d rather look forward to the future.

Be careful what you wish for.