Read time 20 minutes

This is another instalment in my blog about family ancestry. However, for this story, I have chosen to go down a slightly different pathway, with a tragic story about three guys who almost disappeared from our family records.

I’ll begin by setting the background about them & the time in Australia’s history, that they came from – the early 20th century.

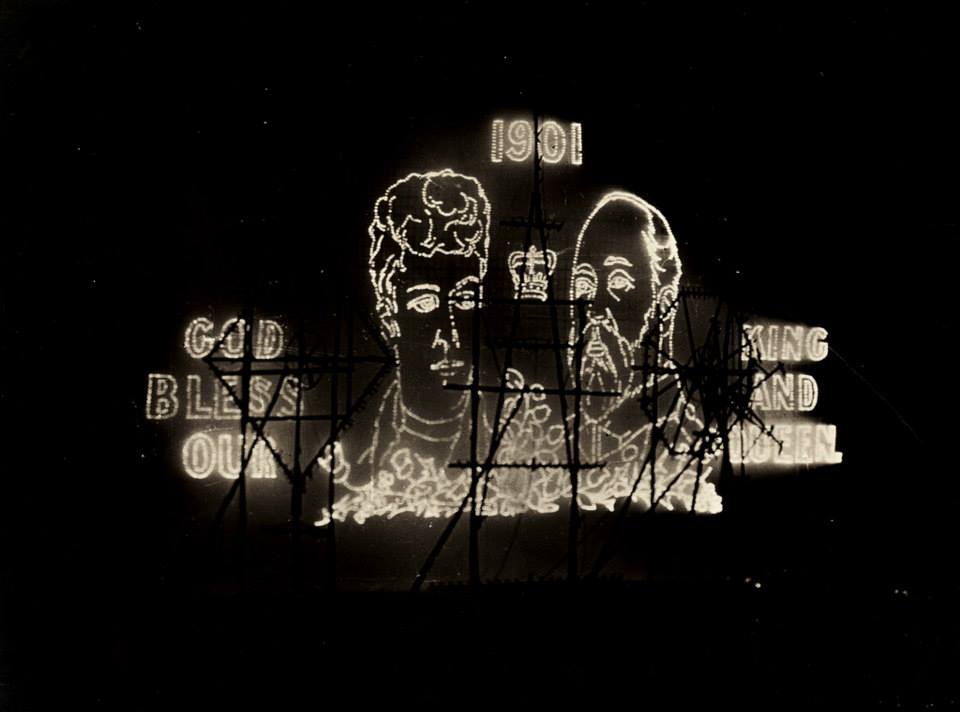

In the Australian landscape of a hundred plus years ago, it was much more conservative, with the vast majority of the population holding strict religious beliefs & strong connections to King & country. Australia had become a sovereign nation in 1901.

As a country, we were still part of the British Empire. We fought wars as part of that empire. The head of the British Royal Family was still our head of state. People had a totally different moral & cultural mindset about how they looked at the world & how the world looked at them. Many of the residents in metropolitan & regional Australian cities & towns held quite prudish, old school ideals & principles. Access to computers & the internet were still the best part of a hundred years away. The general population believed in what they read in the print media of the day. Most of these newspapers had strong right wing, conservative editorial content. It was an era when masonic lodges, strong sectarian views, church groups & secret societies were part & parcel of Australian life. Anyone who wasn’t part of that status quo was treated as an outcast. Radical views & behavior weren’t tolerated or considered acceptable.

In Brisbane, clubs like the Johnsonian, Tattersalls, Corinthian, The Queensland Club, The Brisbane Club, the Royal Queensland Yacht Squadron, and the Constitutional Club were key venues where decision-making processes took place. These exclusive, men-only clubs played a crucial role in shaping leadership circles in Queensland, determining who was included or excluded. Many reputations were made or broken within these elite social spaces.

From a modern perspective, we often look back with a certain degree of judgment on how times and attitudes have changed. However, it was an era when government and authority held significant control.

I have included the following chapter of my three uncles in my blog because it applies to a part of our family history that we are not proud of, but nevertheless is part of the story.

I have found in chasing the trail of past relatives, that most families had a few skeletons in the closet. There appears to have been a generational attitude by our conservative ancestors who had what they felt were embarrassing issues, that may have brought shame on the family name & they didn’t want these spread to the outside world. There were many things that family’s wanted kept out of the limelight. Maybe a crime was committed & jail time served by a member of the family. It could have been debts, bankruptcy or some shady dealings that the family weren’t proud of & didn’t talk publicly about. It could also have been having a relative being outed as gay, having a mental health disorder or being handicapped in some way.

Any family that believes that they didn’t have any dark secrets in those times, is kidding themselves.

Often times in the old days, the disabled or handicapped members of our communities were labelled as retarded, embeciles or other similar descriptive names. Some families chose to quietly have them shunted off to state run facilities, where they were supposedly cared for. Out of sight, out of mind!

In modern day Australia, people with mental health disorders (born with or aquired), drug or alcohol dependency, stress related issues or more serious psychiatric problems, can get access to assistance & medication to treat & to help them manage their conditions. Most fit into everyday society, living an assisted lifestyle, get an education, learn coping skills, have a job, a relationship & live normal lives. The system isn’t perfect, with many still slipping through the cracks, but it is better than what it was a hundred years ago.

Unfortunately, in years gone by, many of these adults & kids, who suffered from any mental health disorders were sectioned & placed into a mental health facility, without any recourse.

We are now finding out, with the brutal stories surfacing from Queenslands dark history of mental health care, about the practices that took place in these institutions.

Our family had three brothers (Kevin 1908-1996, Peter 1912-1956 & Michael 1915-1998) who were institutionalised at Wolston Park Asylum in the 1940’s & spent practically their entire lives there. The brothers were born with an intellectual disability. They weren’t physically disabled & could communicate reasonably well, but were always going to need some form of assistance to navigate their way through life. As kids, they grew up in Boonah & on the farm in the Fassifern Valley where they were cared for. Given menial tasks they were quite ok with working under supervision.

It is something I only learned about well into my adulthood, because no one in the family ever spoke about them. They were looked after by their immediate & extended families, until those families were no longer able to do so.

I’ll try & paint a verbal picture of their story. In doing so, it’s worth deviating, to explain the history about the mental health care system, into which they were placed. It was a particularly hard story for me to write, because I knew very little about them, due the veil of secrecy that surrounded the brothers. Although they were born a long time before me, part of the story of their troubled lives, took place in my own lifetime. Unlike many other relatives from past generations, I actually had the opportunity to meet two of them, albeit shortly before they died.

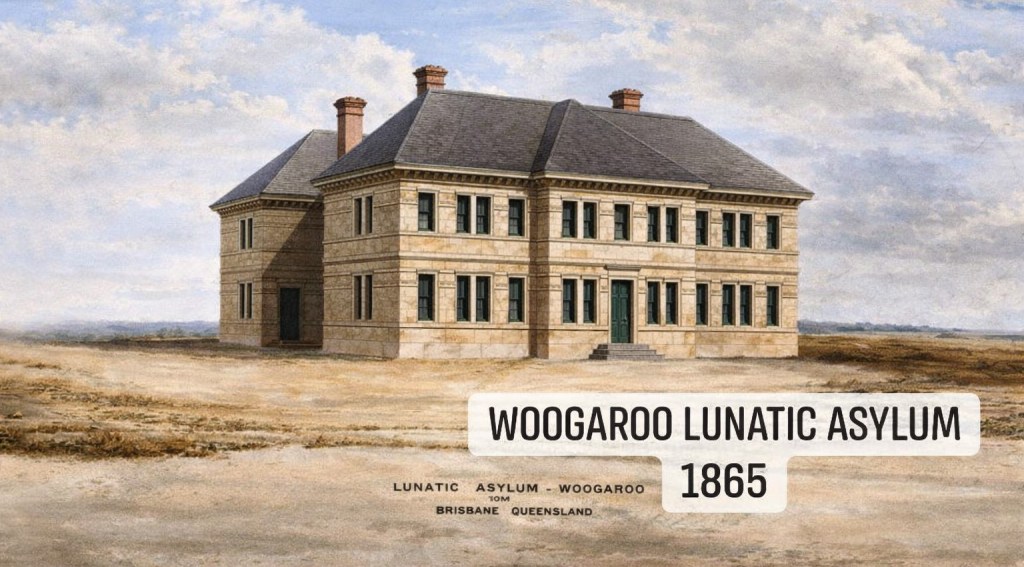

They were placed into a broken down, state run, mental health care system that was operating in Queensland in the 1940’s – the Wolston Park Asylum, which was part of the Queensland Mental Health Care network. Since it’s inception, this system had been used as a dumping ground for vulnerable handicapped people no longer capable of independently looking after themselves. It had been constantly renamed over the 155 years of its history. First, the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum in 1865. It is currently called The Park Centre for Mental Health.

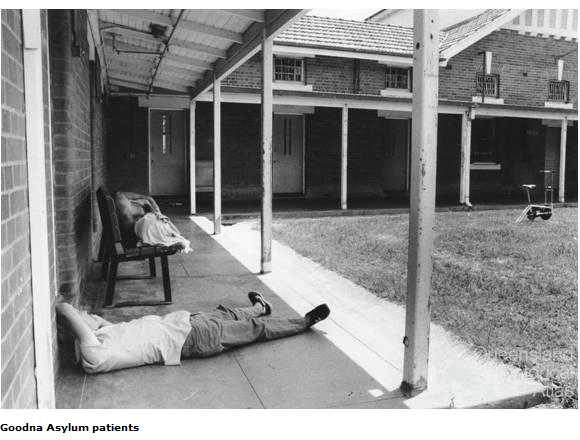

Post war, Queensland Government expenditure, was concentrated on infrastructure planning, civil rebuilding & getting the economy, & life in general, back to normal for Queenslanders. The individuals who ended up in state care at the time, were the least of the governments priorities. They were left in a run down psychiatric facility where all patients were subjected to similar types of treatment, despite having been diagnosed with vastly different types of mental & physical health conditions. These treatments were also given to patients who had relatively minor intellectual or physical disabilities.

Deaf and visually impaired individuals were sent there. People with epilepsy and the elderly experiencing cognitive decline were also institutionalized. Men, women, and children on the autism spectrum, those with Down syndrome, individuals suffering from depression, drug addiction, and alcoholism, as well as those who were simply poor, uneducated, or had fallen on hard times, were all committed. Anyone in those categories, whose family could no longer care for them, was sent to Goodna.

Sex workers and vagrants were frequently taken there by the police. War veterans who returned with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were also confined within its walls. This was a time when homosexuality was illegal, and gay men were incarcerated there, often subjected to chemical and surgical castration as a so-called treatment.

At the other extreme, individuals with severe antisocial, psychopathic, and violent personality disorders were housed in the same facilities. Violent & sexual assaults—between patients, between patients and staff, and even by staff against patients—were commonplace.

Some women were sent to Wolston Park suffering from Post Natal depression. It was also an era when husbands, with the aid of an obliging GP or the local cop, could commit their wives, claiming they were suffering from an emotional mental disability. A Justice of the Peace could even sign the relevent paperwork committing a person to the facility. One wonders, how many victims of domestic violence were taken there under the guise of their emotional state.

The women’s wing was where many young & vulnerable girls under state care were also sent. Many of these kids had come out of the equally terrible government sanctioned religious orphanages. They were considered damaged goods & never stood a chance of any rehabilitation from what they had already been subjected to. There have been some horrific sexual assault stories emerge about what took place in Wolston Park since it’s inception. Abortions were performed on rape victims who fell pregnant. Women and teenage girls who carried their pregnancies to full term had their children removed and placed in orphanages, where the cycle would then repeat.

The violent and sexual assaults by staff were rarely investigated, and there were virtually no repercussions. Violence against patients was considered an acceptable consequence of treatment in Queensland mental asylums during the 20th century. The police seldom conducted investigations. The State Mental Health Act ensured that asylums operated with impunity. The general population of Queensland was either blissfully unaware of what occurred in these institutions or simply indifferent. Even when people were aware, they often perceived asylums as facilities housing mentally impaired inmates—straightjacketed, drugged, and kept in a zombie-like state. Society largely turned a blind eye, viewing those in asylums as lost causes.

Throughout the history of the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum, later known as Goodna Hospital for the Insane, Brisbane Mental Hospital, Brisbane Special Hospital, Wolston Park Asylum, and currently The Park—Centre for Mental Health Treatment, Research, and Education—there were also many dedicated staff members who genuinely sought to provide care, despite the limited resources and options available to them. Many clinicians, nurses, and other workers were often bullied and victimized by their own colleagues. Those who tried to raise awareness about the issues were frequently ignored or forced out of the workplace.

One of the other tragic consequences of the facility’s proximity to the main western rail corridor was the number of suicides. Many patients, in their desperation to escape the trauma they endured at the asylum, jumped in front of trains. The tracks were only a ten-minute walk away. It was common knowledge in the surrounding suburbs that numerous inmates had taken their own lives. Police were regularly called to incidents, leading to temporary rail network shutdowns. I seriously doubt that any records were kept regarding the number of suicides at Wolston Park over the years. Like the assaults, these tragedies were likely kept under wraps.

This was also along the timeline of mental health treatment, when experimental psychotic drugs, tranquilisers, frontal labotomies, straitjackets & shock treatments were used by clinicians to treat people with psychiatric ailments. In that period, many who went in to Wolston Park Asylum for treatment, if they survived & were discharged, came out in a worse state than when they were admitted.

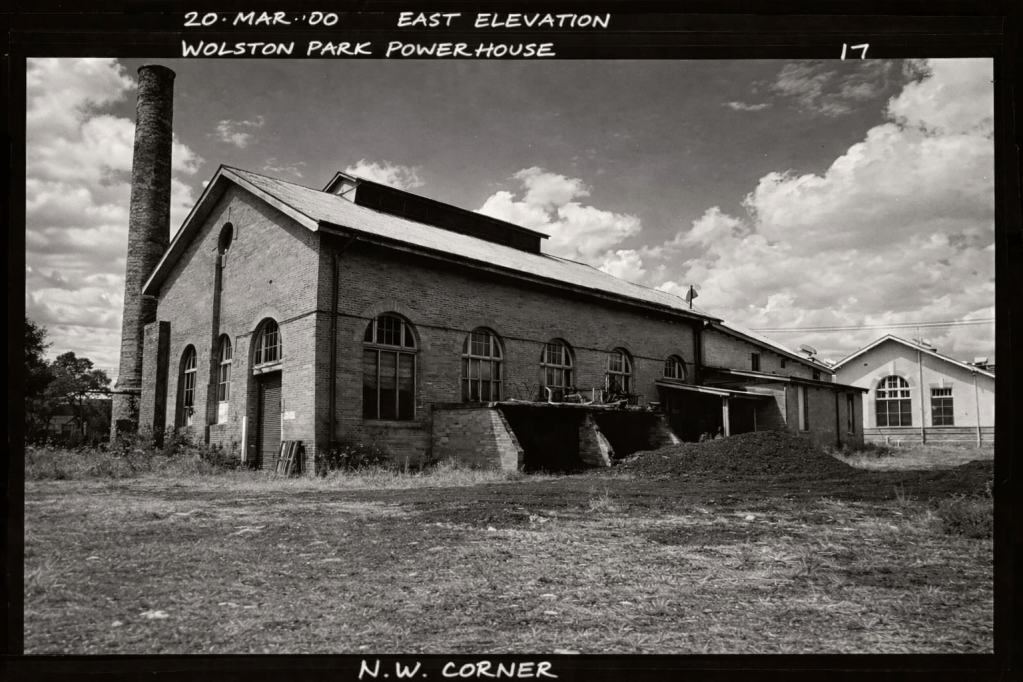

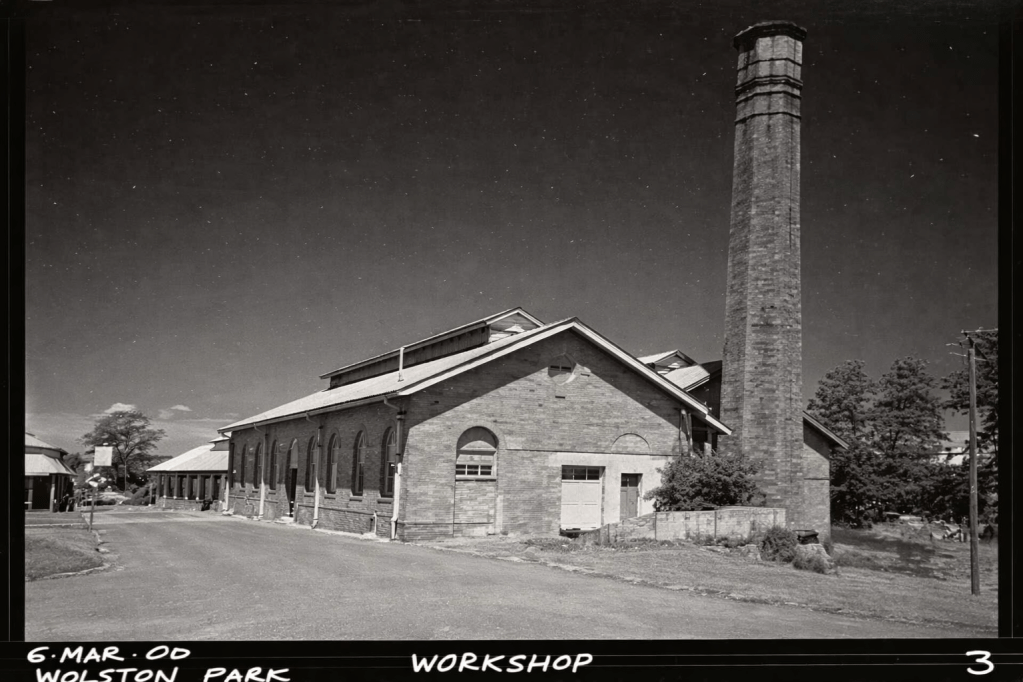

Wolston Park Mental Health Facility had its own power station, farm, factories, laundry, workshop, hospital and surgery, morgue, chapel, and cemetery. It was a fully self-contained institution, run and administered by the State Government.

Over its 160-year history, administrators came and went, while shifts in government, policy, and funding were frequent. These changes contributed to a steady decline in the standard of patient care. Approximately 50,000 people were admitted during its operation, which began in the mid-19th century. The disturbing reality is that this facility operated just 30 minutes west of Brisbane’s CBD—hidden in plain sight.

The abuses that occurred remain locked behind closed government archives, protected by legislation designed to shield the institution from scrutiny and legal repercussions. Over the past 160 years, numerous official inquiries have examined the administration and operations of Wolston Park, including one currently underway. Yet, many of these investigations resulted in recommendations that were never implemented. Public confidence in the latest inquiry remains low, with many believing it will be no different from those that came before it.

To this day, the trauma experienced by former patients and their families continues to cast a long shadow.

In 1992, I learned about the existence of the brothers while attending a family funeral in Melbourne. Shortly after returning, I visited Kevin and Michael, both of whom were very old men by then. Peter had passed away many years earlier, in 1956. By this time, Kevin and Michael had been relocated from Wolston Park and spent their final years at the Eventide Aged Care Home in Sandgate, on Brisbane’s northern outskirts. The visit was eye-opening, as both shared a strong family resemblance. At that stage in life, Kevin was largely uncommunicative, but Michael was still able to tell me that he was looking after his older brother. Having spent the majority of their lives in the dreadful conditions of Wolston Park Asylum, I could only guess at the quality of life they had endured in that place.

Shortly after, I had to organize the funerals when they both passed away. I was the only person who attended the services. The chapel at Eventide was empty, aside from myself, the priest, and the funeral staff. It was unsettling at the time, knowing that these two old men, both well into their 80s, had lived and died with very few people in our family knowing or caring about them. Sadly, I didn’t know enough about either of them to say a few words at the service. Even from my childhood memories, I could only vaguely recall brief mentions of these mystery men, which were usually followed by silence or a change of subject. As children, we often overheard stories about many older relatives, but most of those conversations didn’t mean much to us at the time.

This chapter, which describes what happened to my uncles, has naturally led into a broader discussion of the Queensland Mental Health system—particularly Wolston Park—during the period they were confined there. In doing so, I hope to have provided you, the reader, with some insight into their lives within that institution.

I don’t want to sound too sanctimonious about this family matter, but it seems the initial and ongoing decision to keep these men a secret and hidden from the outside world ultimately succeeded. Whether or not they experienced the many horrors that occurred at Wolston Park, I have no way of knowing for certain.

Is there any blame or guilt to be assigned to past members of our family?

To answer that question—it’s too far down the road to start assigning blame. I believe they took what they thought was the right course of action at the time. However, with the benefit of modern hindsight (which is a wonderful thing 😃), the brothers may have had a much better chance of leading more fulfilling lives had they been born in a different era.

In the first half of the 20th century, there were no government-assisted living programs, no sheltered workshops, and no formal support for people with disabilities. When family elders could no longer fulfill their caregiving responsibilities, they had few—if any—alternatives.

By the mid-1940s, when the brothers were admitted to Wolston Park, their father—my grandfather—had recently passed away, and their mother—my grandmother—was approaching the age of 70. It must have been a difficult and emotional decision for her at the time.

Stories like this were common then and still occur today, particularly when aging parents can no longer care for adult children who have become physically stronger and more challenging to manage. In our case, my grandmother was no longer capable of providing the level of care her sons required.

Apparently, she visited her sons regularly until her age and declining health made it no longer possible. As far as I can determine, she continued these visits until the late 1950s. She passed away in 1965 at the age of 88.

My dad also visited his brothers from time to time, often accompanied by my brother John, but these visits became increasingly infrequent as the years went by.

I have no way of knowing how well they would have coped if they hadn’t been locked up at Wolston Park all their lives.

For the three brothers, as the years and decades passed at Wolston Park, all of their relatives from their generation had either died or forgotten about them. With a touch of irony, after everything they had been through, Kevin and Michael eventually outlasted all of their siblings, cousins, and many members of the extended family. As far as I can determine, they were both there for well over fifty years. They hadn’t committed any crimes or harmed anyone but were simply sent to Wolston Park for being mentally handicapped. It is fairly safe to assume that all three brothers became institutionalized after being there for so long. They would have had very little knowledge or understanding of the world outside Wolston Park.

It is certainly important to have a conversation about what happened to Kevin, Peter, and Michael. I hope that our current and future family members can have a mature discussion about their lives and acknowledge their existence rather than ignoring it, as has happened in the past. From what I can gather, there seems to have been a troubling suspicion that there might be a genetic link to their condition and that it could be passed on. This suspicion appears to have been the driving factor behind locking up the three harmless brothers for over half a century. Out of sight, out of mind! I can only conclude that many in the family kept this a secret for that reason.

While I understand that dwelling on the subject of Kevin, Peter, and Michael—and the terrible lives they were forced to endure at Wolston Park—does not change anything, it doesn’t stop me from feeling some anguish for what they had to endure. I can only hope that they found some peace and contentment before they died.

We also had a relative in our family history who was gay, and from what I can determine, he was likely a distant cousin. Any trace of him has been almost entirely erased from family records. Uncovering more information about him remains a work in progress, but I’m determined not to give up. In time, I am confident I’ll find more to connect him to our family. He deserves acknowledgment, regardless of how poorly or unfairly he may have been treated by his relatives.

To understand the mindset of that era, it is important to recognize the ultra-conservative and deeply religious stance that dominated most small-town & regional communities at the time. Back then, being gay was entirely unacceptable, and families often ostracized any member who did not conform. It was regarded as an abhorrent lifestyle, and those who identified as gay were frequently expelled from both the family and the wider community.

UPDATE – I believe I have tracked down & identified the mystery gay man in our family history. His name was Colin. Clarifying his story is ongoing, and my intent is certainly not to disparage him in any way. I feel profound sympathy for the hardship he must have endured—not only from his own family but also from the community at large. From the scant records I’ve unearthed, it seems he was never married and passed away relatively young, at the age of 41. He apparently returned to the Boonah/Fassifern area for a time, but, as was common in those days, he was forced to leave again. Colin worked as a farmhand, holding various jobs throughout southeastern Queensland, moving from place to place before dying in 1970 in Bundaberg.

I recently connected with an elderly family member who knew of him, but they were hesitant to share details. Even in 2024, it seems some people still cling to the same small-minded, bigoted attitudes of the past, maintaining a wall of silence.

I personally recall growing up in Australia during the 1960s and 1970s, a time when minority groups were often treated as spectacles—ridiculed and mistreated rather than embraced. Thankfully, society today offers more opportunities for marginalized and downtrodden groups to be treated with fairness and dignity.

No doubt, as more and more information gradually comes to light about the history of Queensland’s mental health system, I will be able to add a few more pieces to complete the puzzle of the three brothers’ lives.

The stories of Kevin, Peter, Michael, Colin, and possibly other family members I have yet to uncover highlight the deeply ingrained bigotry and near cult-like secrecy that some families maintained toward individuals from minority groups, including those with disabilities. This discriminatory mindset was not only widespread a century ago but, regrettably, still persists today.

These individuals were just as integral to our family history as any other ancestors. Through no fault of their own, they were born into a world that refused to accept them for who they were. They were placed in horrific environments far beyond their control—institutions where they were supposed to be cared for but instead were left to fend for themselves in frightening, dehumanizing conditions. For the three brothers, it must have felt like something out of a horror story. For the families they left behind, it was simply a matter of being out of sight, out of mind.

December 2025 EDIT – On 8 August 2024, the Queensland Government announced the independent Wolston Park Hospital Review of health services provided at Wolston Park Hospital between 1 January 1950 and 31 December 2000.

The Review was led by mental health expert Professor Robert Bland AM and provided an opportunity for former patients and family members or carers to describe their experiences during the period.

On 19 December 2025, the Queensland State Health Department released the final report into the operation of Wolston Park. The report, accessible via the provided links, details the atrocities that occurred during its years of operation, including the period in which the three brothers were there for more than half of their lives.

This report makes for confronting and distressing reading. It contains descriptions of physical and sexual violence and serious human rights abuses, as recounted by participants who contributed to the Review.

For my two cents’ worth, it is easy to look at the situation from the outside, adopt a holier-than-thou attitude, and draw conclusions. However, it is important to acknowledge that many deeply troubled individuals in that place had severe psychotic mental health conditions. These conditions meant they were not only capable of self-harm but also of inflicting serious injury—or worse—on other patients or staff.

At times, staff had no viable option other than to administer stupefying drugs or use other control measures. That said, the real issue lies in the extent to which some staff went to control patients who posed no danger to anyone. It became easier for staff to take the path of least resistance—making their shifts less demanding by drugging and stupefying the majority—rather than fulfilling their duty of care and properly doing their jobs.

Many of the details in the report were widely known prior to its release. However, its formal entry into the public domain makes the claims about what occurred in the hellhole known as Wolston Park Asylum even harder to digest—particularly given that the investigation covered only the years from 1950 to 2000.

I have read numerous responses from people who worked there attempting to justify what took place, offering explanations and rationalizations to legitimize their actions (or lack thereof) under the guise of providing care to individuals who were unable to complain or resist their predicament. Many of those involved—both patients and staff—are fully aware of the identities of those persons involved in the horrendous behavior that took place under the guise of treatment.

I understand that making names public is unlikely to happen, but some of the senior figures & staff members who oversaw the operation of this house of horrors should be held accountable. I cannot help but think of how the Nazis during World War II, and other brutal regimes past and present, attempted to justify their treatment of disabled people while hiding behind administrative authority and the belief that the end justifies the means.

That argument does not wash with me and never will. In my view—and this is purely a personal opinion—if you recognized that what you or your colleagues were doing was wrong, the moral responsibility was to report it & do the right thing for the patients. Sadly, we all know that during much of that time, the powers that be had no intention of doing anything about it. But accepting it as permissible is indefensible.