Read time 15 minutes

From a sideline perspective, I’ve been watching with great interest as Queensland’s newly elected LNP government, voted in largely on a single-policy platform of youth crime and punishment, begins to implement its new policies. Like any opposition party, it was easy for them to criticize the sitting government, even if the incumbents were performing reasonably well. Winning elections often hinges on striking a chord with voters, and unfortunately, in Queensland—as in other Australian states—that chord is frequently crime and punishment.

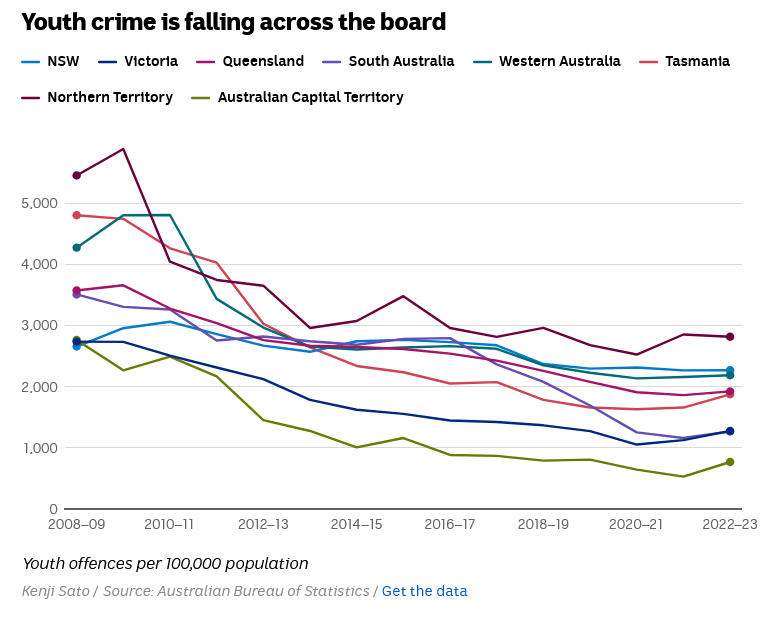

Australian news outlets and politicians in opposition have repeatedly claimed the country is in the grip of the worst crime wave in history.

These claims are contradicted by official data sources that show rates of crime have plummeted in every state and territory in Australia to near record lows.

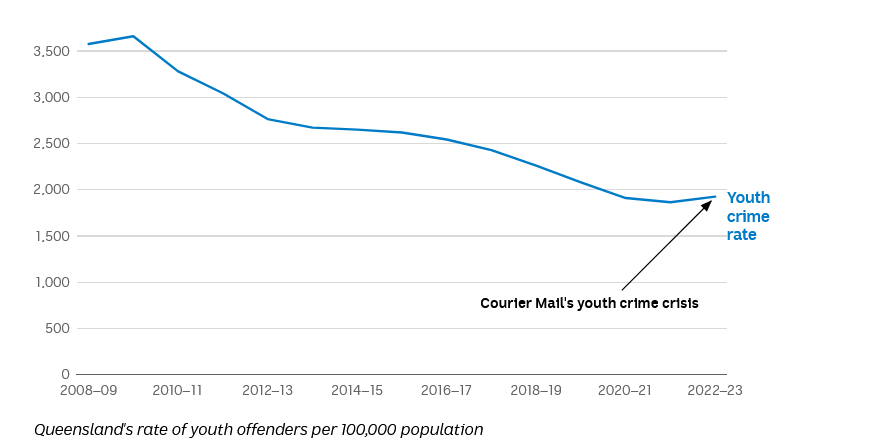

Let’s analyze these figures. In 2001, Queensland’s population was 3,670,500. By 2024, that number had grown to 5,560,452. Unless I’m misreading this graph, it appears that despite a significant increase in population—nearly two million more people—we’ve actually seen a considerable drop in the actual number and rates of criminal offenses during this period.

If I’m understanding this correctly, we’ve seen a 65% increase in the state’s population, yet both the total number and rate of crimes have decreased. Please correct me if I’m wrong, but this suggests that crime is not rising in proportion to population growth.

Honestly, I find these media claims a bit confusing—or do I? Did you know there are no laws anywhere in Australia against lies in political advertising campaigns by parties or media outlets?

Are these media hacks incapable of properly interpreting statistics? Did they fail to grasp the skill of reading a graph accurately? Or did they not make it past grade-five mathematics in school? That could explain part of the problem. However, it’s more likely that they are simply following the directives of their politically conservative media bosses and publishers, who naturally hold a bias toward their favored political parties. These parties often align with the media’s business interests. As a result, manipulating statistics and graphs to suit their agenda becomes easy. They can twist the data to serve their own interests, sell more newspapers, and boost ratings.

The Murdoch media through its local newspaper The Courier Mail has claimed that Queensland’s youth crime rates have skyrocketed to crisis levels. Maybe I’m struggling to correctly read the actual figures from these graphs collated by the State Government statiticians.

This issue is a popular campaign platform because, for the vast majority of people, crime feels distant. Most citizens go about their daily lives—enjoying our relaxed Australian lifestyle, working, studying, paying their bills, and adhering to the law. Interactions with law enforcement or the justice system are typically limited to minor infractions, such as speeding or parking violations, which result in fines that are paid, and life moves on. Laws exist for a reason, and while some may grumble about specific regulations, like a 60 km/h speed limit, they generally accept that these rules are in place for public safety & the greater good.

You only truly feel the impact of serious crime when it happens to you or someone you love. For most, crime is a story you read about or hear on the news. But when it becomes personal, such as through a break-in, a stolen car, an assault, a rape, or the loss of a friend or loved one to murder, it’s a completely different reality. In those moments, no matter what anyone says, the immediate response after the grief is a desire for retribution.

The vast majority of crime victims want justice – an arrest, a conviction, and a harsh jail sentence. They want those responsible to suffer for the harm they’ve caused and to be removed from mainstream society. There’s little room for sympathy or rehabilitation in these circumstances; the priority is safety and punishment.

The Role of the Media

Media outlets survive, expand or die by viewer numbers, circulation figures or hits on a website. All media organizations understand that simply reporting the facts about crime won’t drive TV ratings or newspaper sales. When a particularly serious crime occurs—such as the tragic death of a child or a hit-and-run incident—the media descend like seagulls on a stack of chips, each competing to outdo the others with their spin and opinions on the tragedy. It becomes a competition to stoke outrage among their audiences.

In the last decade or so, with the rise of social media, mainstream newspaper and TV outlets have perfected the art of using platforms like Facebook, X, Instagram & Reddit to fan the flames of public anger and push it to maniacal levels of vigilantism. The involvement of influential figures like Elon Musk and Rupert Murdoch in the editorial processes of these platforms adds further momentum to this trend.

When an offender is caught and arrested, the entire saga is endlessly repeated during the court case, with daily coverage that heightens public outrage and calls for retribution. The media often fuel hatred to almost ridiculous levels, resembling a vigilante mob seeking revenge. Let me be clear: I’m not advocating sympathy for serious offenders. However, all forms of media need to take a long, hard look at how they present the news today. Do we really need a media that makes our minds up for us? Are we so stupid, in modern times, of reading a factual report about an incident without the added sensationalism that media outlets insist on pushing to provoke a frenzied attack on an individual who is supposed to be innocent until proven guilty? Unfortunately, I don’t see this changing anytime soon.

Consider this: if the offender is a low-profile individual from a disadvantaged area, you can almost guarantee a swift, savage, and relentless media pile-on. Conversely, if the offender is young, upwardly mobile from an affluent family in an upscale neighborhood, and represented by an expensive lawyer, the coverage is far more subdued. In such cases, the story may be buried in a late-night news segment—if it airs at all.

Whoever said the scales of justice are the same for everyone is living in a make-believe world.

While many advocate for compassion and the rehabilitation of offenders—arguing that they’ve lost their way in society—the hard truth is that most people, when personally affected by crime, want the perpetrators locked away indefinitely. Anyone who claims otherwise is seriously underestimating the depth of anger and pain such experiences evoke in victims & their families of violent crimes like assault, murder, or rape.

However, as elections approach, politicians and media outlets amplify stories about the failings of the justice system and the perceived rise in crime. Sensationalized narratives paint a picture of rampant lawlessness and criminals evading punishment.

While youth crime is undoubtedly a persistent issue, election periods often act as a catalyst for fearmongering rather than fostering meaningful discussions or practical solutions. At the same time, domestic violence—an undeniable national crisis—receives far less political attention, as it is not seen as a “vote-winning” issue. Politicians repeatedly prioritize youth crime as a central talking point during election campaigns, a narrative eagerly amplified by the media.

Crime and Its Persistent Nature

Crime, like other societal problems, has always been and will always be part of human existence. Every community includes individuals who engage in harmful behaviors—whether theft, assault, or worse. This has been a reality since time immemorial. Humanity has yet to achieve a society where everyone lives entirely peacefully and lawfully, which is why law enforcement and a robust legal system are indispensable for maintaining order.

Make no mistake: if the police were to take industrial action & go on strike tomorrow, chaos would ensue almost instantly. Incidents of theft, assault, domestic violence, corruption, and even murder would surge at an unprecedented scale. This hypothetical underscores the essential role of law enforcement as society’s “thin blue line”—the fragile barrier between order and anarchy. Without this protection, societal collapse could occur so quickly that most people wouldn’t even see it coming.

Public Perception and the Role of Police

It’s ironic that many individuals who publicly express disdain for the police and authority are often the first to call for help when they’re in need. This dichotomy highlights the complicated relationship between the public and law enforcement.

Like any large organization, police forces are not without their flaws. Corruption, mismanagement, and systemic issues can and do occur. However, as government institutions, police forces are held to a higher level of scrutiny and accountability. This is not an unreasonable expectation; the public deserves to trust that those sworn to serve and protect are doing so with honor and integrity. Queensland’s police motto, “With honour we serve,” serves as a reminder of this duty.

A History of Corruption

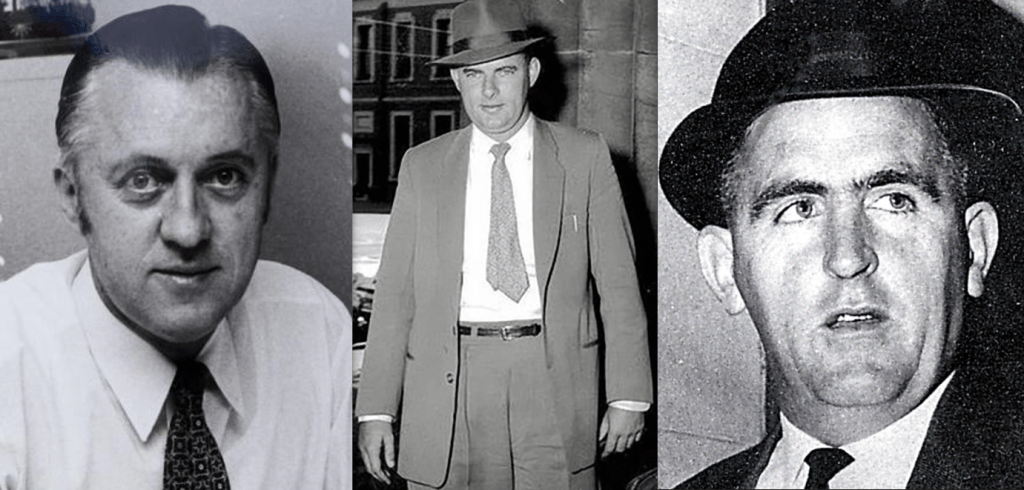

Queensland has not been immune to corruption within its police force. Notably, Commissioner Terry Lewis was jailed for orchestrating corruption at the highest levels of the organization. Books, documentaries, and even movies have explored the extraordinary lengths to which the Queensland police went during the era of corrupt commissioners Frank Bischoff and Terry Lewis. The group known as “The Rat Pack,” composed of senior officers across various ranks, played a pivotal role in perpetuating systemic corruption.

The aftermath of the Fitzgerald Inquiry led to widespread resignations of senior Queensland police officers. It became an embarrassing reality that many high-ranking officers were forced to resign or face prosecution and possible imprisonment. Authorities expressed genuine concern about how many police officers might ultimately end up in jail. At the time, the general consensus was that bringing the top corrupt police officials to justice would suffice, a sentiment driven partly by a desire to shield corrupt political figures in the ruling National Party of the time. Despite these efforts, four politicians were eventually imprisoned. However, many senior corrupt police officers ultimately evaded justice and escaped punishment.

Sadly, this issue is not unique to Queensland. Other Australian states, such as New South Wales and Victoria, have also dealt with senior police officers engaging in criminal activities while leading their departments.

The nature of police work—operating closely with criminal elements and wielding significant authority—creates opportunities for misconduct. This makes it all the more crucial for law enforcement leaders to exemplify integrity and earn the public’s trust.

The “Adult Time for Adult Crime” Policy

As Queensland transitions to its “Adult Time for Adult Crime” policy, public scrutiny will be intense. Ensuring transparency and accountability in the justice system is critical, especially as the state seeks to address the perception of youth crime. However, the challenge lies not only in enforcing these policies but also in addressing systemic issues that perpetuate the cycle of crime.

Prisons in Queensland, like those in many other regions, are severely overcrowded. Rather than serving as institutions for rehabilitation, they often become “universities” for criminals—providing opportunities for inmates to expand their networks and criminal knowledge. By the time many prisoners are released, they’re not only better-equipped criminals but also more embittered and vengeful toward society, making them more likely to reoffend.

Who Bears the Burden?

When these individuals re-enter society, it’s often the police who are left to manage the fallout. Yet the blame for rising crime rates rarely extends to the broader systems responsible for the cycle. Law enforcement becomes an easy scapegoat, while systemic failures in rehabilitation, education, and community support are overlooked.

The media also plays a significant role in shaping public perception of crime. Sensationalized reporting often distorts facts, creating fear and outrage rather than fostering understanding. Editorial decisions driven by media moguls frequently align with the agendas of self-serving politicians, creating a feedback loop that prioritizes fear-based narratives over factual & constructive dialogue.

Recognition of Law Enforcement’s Efforts

Our police officers witness and endure experiences on a daily basis that the vast majority of the population will never have to face. They arrive at crime scenes where people have been violently assaulted or murdered, confronting the brutal realities of what someone’s final moments of life were like. They attend and investigate suicides, trying to understand why someone took the extreme step to end their life—often in profoundly traumatic ways, such as jumping from a building or bridge, or shooting themselves.

Officers deal with the aftermath of violent domestic abuse cases, where women and children have been severely harmed or killed. They investigate cases of abuse against the elderly and individuals with disabilities. They respond to fatal road accidents and carry the heartbreaking responsibility of delivering the devastating news to families about the loss of a loved one.

They investigate violent rape cases, interviewing deeply traumatized victims and analyzing the details of their lives, all while the victims endure immense emotional stress. Officers also manage the chaos that follows street brawls, often protecting paramedics who are attempting to save the lives of the very individuals involved in the fighting.

They are called to scenes where people under the influence of drugs or alcohol have self-harmed and been abandoned, left to fend for themselves. They take into custody violent offenders and, in doing so, are often assaulted, spat on, or even shot at by the offenders, their accomplices, or their families—all while simply doing their jobs.

In courtrooms, they witness these offenders sometimes escaping justice with the help of expensive, manipulative lawyers, only to reoffend and resume their criminal or violent behavior.

Police officers witness the worst of humanity but also occasionally experience its best. They return lost children to their parents, sharing in the immense joy and gratitude of families relieved to have their loved ones back safely. They save lives by talking people back from the brink of suicide, responding to emergencies, assisting in rescues, administering CPR, or simply being there to help in critical moments. Officers also rescue animals that wander onto busy roads, often preventing major accidents.

Tragically, there are times when they must use their firearms to take a life if a violent offender poses a serious threat to public safety.

After enduring all of this, officers clock off and return to their families, where they are expected to carry on as if everything is normal—helping their children with homework, attending family sporting events, and fulfilling household responsibilities. Families often face persecution simply because their parent or spouse is a police officer.

The next day, these officers wake up and do it all over again. It’s a tough gig.

Having said all of that, the police need to earn and maintain public respect. Given the tough and often thankless nature of their work, the rank-and-file police officers generally already have it. The public is quick to criticize law enforcement when things go wrong but rarely recognizes the countless positive contributions officers make daily.

The police must continuously strive to clean up their own act. Recent findings from Queensland Human Rights Commissioner reveal troubling issues within the Queensland Police Service (QPS). The Human Rights Commissioner stated that QPS’s “workplace culture and systems have allowed discrimination to thrive.” These systemic problems have deeply impacted the morale and safety of its members, with one individual remarking that they would never allow their daughter to join the force because, “You just get bashed and beaten, and you know you’re not safe. And you can’t tell anyone about it, because it’s going to be worse for you.”

The recently released review by the Queensland Human Rights Commission (QHRC) paints a damning picture of QPS’s internal culture. More than 2,800 current and former staff participated in the study, revealing a toxic environment rife with sexism, racism, and exclusion. Women in the force have reported being accused of “sleeping their way to the top,” while racist behavior has often been dismissed as “banter.” Those outside the so-called “boys’ club” are frequently overlooked for promotions, and individuals who speak up against these injustices are labeled “dogs” and ostracized.

One QPS member remarked that the community would be “absolutely mortified” if they knew “some of the stuff that goes on.” Another chillingly compared the relationship between QPS and its staff to “domestic violence.”

Despite occasional negative press from certain sections of the media, the general public generally respects the work that police officers do. Negative coverage often stems from the misconduct of a small minority of officers rather than the rank-and-file uniformed officers who are on the front lines, protecting us daily. This isn’t to suggest that all plainclothes officers are corrupt or unethical. However, corrupt practices often begin in the less visible areas of policing, away from the public eye. It is within these “behind-the-scenes” operations that dishonest officers, unscrupulous businesspeople, unethical media figures, and corrupt politicians often collaborate. Nevertheless, the vast majority of police officers are committed to serving and protecting the public.

Addressing Systemic Issues

These findings highlight the urgent need for the QPS to address its workplace culture and restore trust, not only among its staff but also with the wider community it serves. Such revelations are deeply concerning in a profession tasked with upholding justice and fairness. They also exacerbate public skepticism about law enforcement, compounding the challenges officers already face in carrying out their duties.

Police officers are tasked with maintaining order while contending with inefficient laws and the fallout from poor policymaking. They often bear the brunt of public criticism for issues outside their control, becoming scapegoats for political failures. Instead of addressing the root causes of crime and systemic problems within the police force, politicians frequently engage in grandstanding to appease voters, leaving law enforcement to deal with the fallout.

Women in Our Police Service

The police department has long struggled with issues surrounding women in its ranks. This isn’t necessarily about individual officers, but rather the systemic culture that positions the police as figures of authority and power—an image often tied to traditional, male-dominated ideals. Historically, many women have been taught from a young age to respect police officers and view them as trustworthy protectors. However, police services worldwide face a significant challenge: a pervasive lack of respect for women’s capability to perform police work.

In reality, there are countless women who excel as police officers, demonstrating skill, dedication, and competence. Yet, within the Queensland Police Service, there exists a deeply ingrained belief that women are inherently inferior in this field. Over time, women in the service have been subjected to relentless mistreatment and exclusion by the so-called “boys’ club” culture, often leaving their positions due to the unrelenting ostracism.

The Queensland Police Service continues to operate under outdated, 1960s-style leadership dominated by men. While occasional efforts are made to appear more progressive, any genuine advancements are frequently undermined by entrenched sexism, racism, and the powerful influence of the police union. This union is often at the forefront of resisting equality and pushing back against inclusivity. Weak senior management, even at the commissioner level, frequently capitulates to the union’s directives, perpetuating the toxic culture.

While the Queensland Police Service publicly promotes an image of inclusiveness, its internal practices often tell a very different story. If the service is to truly embrace equality, it must confront its entrenched biases and take meaningful steps toward creating a genuinely inclusive workplace. There is a significant amount of work to be done to bridge this gap and rebuild trust.

Restoring Accountability and Trust

For the QPS to move forward, meaningful reform is required. This includes fostering a culture of accountability, equity, and respect within the organization. External oversight, rigorous training, and a commitment to eradicating discriminatory practices are essential to creating a workplace where officers feel supported and safe. Moreover, addressing these internal issues is critical not only for the welfare of police officers but also for maintaining the public’s trust in the institution.

Ultimately, the success of law enforcement depends on its ability to uphold the principles it is sworn to protect—justice, fairness, and integrity. Without addressing these systemic issues, the QPS risks eroding the very foundation upon which it stands.

The Law and Our Indigenous People

This particular facet of the discussion is one that will never achieve complete agreement among all the different groups involved. The reality is that, as a nation, we have yet to find the right path to properly care for and support our First Nations people. We haven’t succeeded in this since January 26th, 1788. The history of our treatment of Indigenous Australians has been, quite frankly, a catastrophic failure.

In fact, if someone were to intentionally design a plan to systematically erode the existence, dignity, and culture of an entire race over centuries, it’s hard to imagine how they could have done a “better” job than the policies and practices we have implemented over the years. As a nation, we are now trying to right these wrongs, but significant portions of our society still hold to outdated, prejudiced views, including the belief that the solution lies in erasing Indigenous culture entirely. While the White Australia policy was officially abolished over half a century ago, Australia remains a deeply racist country. The most glaring example of this is in our treatment of First Nations people—the very people who have lived on this land for over 50,000 years before colonial settlers arrived.

Given this history, is it any surprise that Indigenous Australians make up the highest proportion of those incarcerated?

So, what’s the answer?

It’s clear that whatever approaches we’ve taken in the past either haven’t worked or are still failing. The issue is complex, deeply entrenched, and self-inflicted, with neither side of the debate offering a solution that fully resolves this crisis.

As I see it, we need to draw a line in the sand and start again. Admittedly, this is easier said than done. Many people—both Indigenous and non-Indigenous—struggle to view this as a starting point due to the generations of pain and suffering inflicted on First Nations people. However, I believe that we must try. If we don’t, Australia will still be wrestling with this divisive issue a hundred years from now.

We must address the divisions between white Australians and First Nations people, and we must stop racial intolerance now—immediately, today.

The Rule of Law

I believe the rule of law should apply equally to everyone. We live in an Australia that is striving to be inclusive, though it has a long way to go.

This raises an important question: as the enforcers of the law, how do the police address this issue?

As I said, the law must be the same for everyone—regardless of whether you’re white, black, rich, or poor. If someone breaks the law in Brisbane, Townsville, or Mount Isa, the legal repercussions—penalties, fines, or custodial sentences—should be the same across the board.

Achieving this equality would require significant changes to our legal system, courts, and jails. Personally, I’ve long been a proponent of mandatory sentencing. I don’t believe anyone should receive preferential or discriminatory treatment based on their skin color or their position in society. It’s time to overhaul our legal system entirely.

Education and Rehabilitation

One critical area of reform should be in providing opportunities for education within our prisons. This should be mandatory, and early release for non-violent offenders could be offered as an incentive—but only based on actual results achieved by the incarcerated individual. No progress, no reduction in sentence. This approach would apply equally to both white and Indigenous offenders.

We need to view everyone in our legal, policing, and prison systems as equals. The color of their skin should never come into consideration.

What happens to the bad guys?

As I mentioned earlier, many people in the general public would prefer to see criminal perpetrators locked up and the key thrown away. I must admit, in many cases, this sentiment doesn’t seem entirely unreasonable. However, when addressing the issues of overcrowded jails and high rates of criminal recidivism, we need to develop a better, long-term plan. This plan should aim to keep individuals out of prison while fostering a crime-free lifestyle that benefits both them and the safety of the community. It costs an exorbitant amount of money to house a prisoner in a Queensland jail, with the annual cost being approximately $125,000 per prisoner. That works out at a total figure of well over $1 billion per year. Take a minute to let that figure sink in – $1 billion. You could get an education at Harvard University for less than the cost of being incarcerated in Queensland. I believe it’s safe to say that most of us would prefer to see those funds allocated elsewhere.

I firmly believe that perpetrators should be held accountable for their actions. If someone steals, embezzles, or destroys property, they should be required to repay what they have taken or damaged in some form. This process might take time, but it is one thing to commit a crime and another to think you can walk away without restitution. Allowing non-violent offenders the opportunity to make restitution instead of going to jail could be a viable option. However, this option must come with strict requirements, including maintaining an entirely crime-free existence during the restitution period. Violent criminals, however, should never be given this option under any circumstances.

This principle should apply across all levels of crime—from lower-level offenses such as car theft to corporate crimes like wage theft or bankruptcies that leave smaller entities unpaid for goods and services they have provided.

That said, there is a group of individuals in the prison system who, for various reasons, may never be reintegrated into mainstream society. Whether due to an abusive childhood, severe mental health issues, or being born into adverse conditions like drug addiction, some individuals have never had a fair chance at leading a normal life. However, there are also hardened criminals whose crimes or deeply ingrained, institutionalized perspectives render them beyond rehabilitation.

For these serial offenders, prison becomes the end of the line. As much as we, as a society, strive not to give up on anyone, there may need to be places where such individuals are permanently removed from normal society for the safety of everyone. While it may sound harsh to confine someone for life, there are cases where doing so is necessary to protect the community.

Conclusion

Queensland’s new government has its work cut out as it tackles the crime and punishment issue. The success of its policies will depend not only on enforcement but also on addressing the underlying causes of crime. Prisons must focus on rehabilitation, and media narratives must shift toward fostering informed discussions. Sadly, the latter is extremely unlikely.

Most importantly, politicians must take responsibility for creating effective laws, rather than using police as scapegoats for systemic failures.

Does the newly elected government have competent politicians capable of leading the state and creating laws that are effective and achieve their intended outcomes? Does the Police Service possess strong and effective leadership through its Commissioner and senior leadership team to unify the force, fostering a proud, robust, and incorruptible institution that serves with distinction, not just today but for the future? Can the justice system, including the courts and prisons, bring about meaningful change by reducing the number of offenders entering the system and lowering recidivism rates? In writing this opinion piece, I am not claiming to have all the answers on this serious issue. However, it is clear that some of the past and current practices in the justice system are not working. As everyone is entitled to their opinion, I believe mine is just as valid as anyone else’s.

It appears that since Queensland was formed in 1859—and in every other jurisdiction around the world—we have struggled with the persistent issue of how to address crime and punishment. On the front lines, the QPS is tasked with maintaining order, often while feeling constrained by systemic limitations & its own self-inflicted issues. Then, we have the courts and legal system, which seem to toss the “crime football” back and forth. Should offenders be sent to jail, or should they simply receive a slap on the wrist and a warning not to do it again? Some criminals are imprisoned, while others are set free to continue their activities.

Among these challenges, the mentally ill are often neglected, with little care or attention given to their needs. At the heart of it all is the majority of the population—ordinary people who primarily want to live their lives in peace and contentment.

I sometimes feel that we are just pissing into the wind & that nobody has the answers. Only time will tell.

Ultimately, ensuring public safety is a shared responsibility—one that requires transparency, accountability, and cooperation across all levels of society.