Reading time 18 minutes

Out of all my ancestors who came to Australia from Germany and Ireland or in this instance, England, Robert Bradbury would have been the very first to have arrived. Robert was a convict who had been charged with desertion from the British Army.

I’ve mentioned in previous posts on my Irish ancestors about the unbearable control the British government exerted over everything they did in their daily lives. Practicing their religion, the ability to own land in their own country and literally starving them to death through famines & epidemics were just touching the surface of the oppressive rule, the British employed over the population of Ireland.

However, the British were just as heavy-handed in the treatment of their own citizens in England, as well as in the way they treated the people of Ireland, Scotland & Wales.

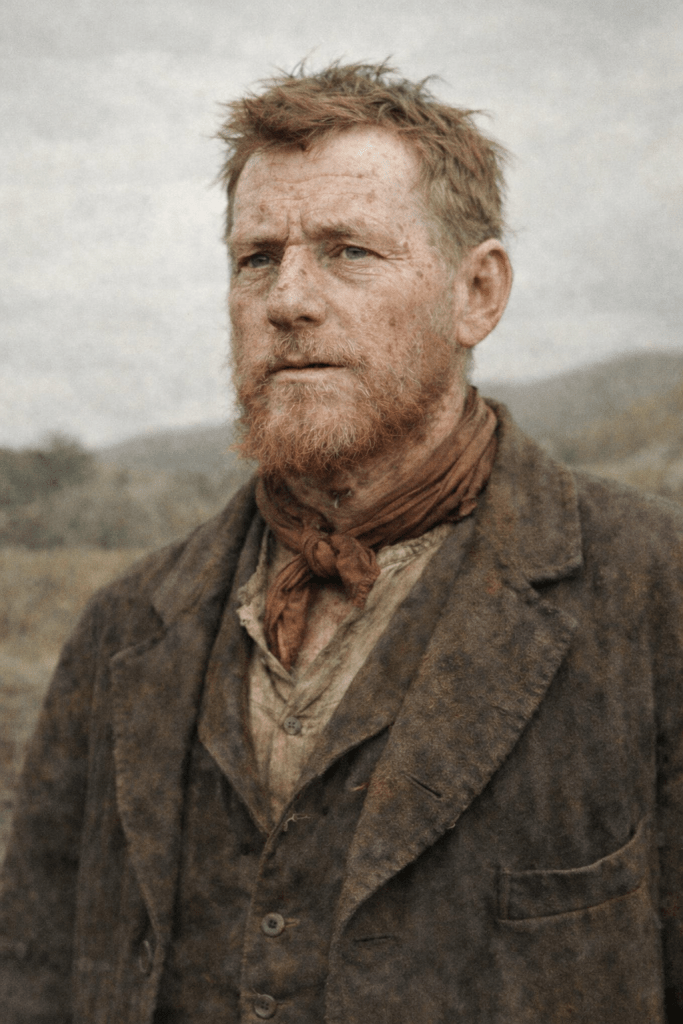

This is the story of Robert Bradbury. We often interpret lives like his through a modern lens, revealing the history, background, and living conditions of the time. By these standards, we might view the events in Robert’s story as part of an adventurous life. But in reality, it was quite the opposite. During Robert’s young adulthood, Britain was undergoing massive transformations. The Victorian era brought sweeping engineering innovations, along with a harsh approach to crime and punishment by the government. This period marked some of England’s most brutal home rule under the British government.

When my Great Great Grandfather Robert BRADBURY was born in 1806 in Manchester Lancashire England, his father William Bradbury was 25 and his mother, Margaret Bridge was 21.

In the early eighteenth century when Robert was born, Manchester was booming, particularly on the back of the cotton industry. The story you will usually hear about Manchester is about the successful trade and commerce that made it the world’s leading industrial centre. Manchester experienced a population explosion, growing from a town of 60,000 inhabitants in 1800 to 142,000 by 1842. The working conditions in the mills were terrible. The air in the cotton mills had to be kept hot and humid (20 to 30 degrees Celcius) to prevent the thread breaking. Most millhands went to work early in the day and labored for twelve hours straight, amid deafening noise, choking dust and lint, and overwhelming heat and humidity. In such conditions it is not surprising that workers suffered from many illnesses. Manchester’s unplanned, unchecked growth led environmental conditions to rapidly degrade. Robert would not have had much of an education in early 19th century England & any chance to advance himself. So, one of his only opportunities as a teenager, other than working in the cotton mills, would have been to join the armed forces. Keep in mind, that back in the 1800’s, service life gave them a job, a wage (surprisingly good at one shilling/day), free clothing, three meals a day, a roof over their heads & a chance to see the world, albeit from behind a gun in a warzone or wherever Britain was trying to invade & conquer with its military might. But it also did teach them some skills, if they survived. Alongside his combat training in the army, Robert Bradbury also learned the trade of baking. Many young men chose to leave Manchester & the other industrial towns & cities of England since they had no chance to get ahead if they stayed. A career in the armed forces gave them a pathway, of sorts. The downside was that many older soldiers were debilitated after serving for years in harsh climates or disease-ridden areas. Many barracks were unsanitary and more overcrowded than prisons and the death rate among men in their prime in barracks in Britain was much higher than that among the general population of Britain. Long-term over-indulgence in alcohol also affected the health of many soldiers though this was rarely admitted in official records. It also was the cause of most disciplinary infractions. In Robert’s case, we’ll get to that subject shortly.

Since Britain had lost the American colonies in 1781, the British government had decided to prioritize interests in the Caribbean, maritime Europe, Canada, Africa and the Indian & Pacific Oceans.

Robert became a soldier, serving in the British Army around the early 1820s. The 96th Foot Regiment was formed in Manchester in early 1824 from the remnants of the officers & enlisted men of the earlier 94th & 95th regiments. Records show that the 96th regiment served at the French intervention in Spain- mid 1824, Nova Scotia -1824, Bermuda -1825, & then back to Nova Scotia in 1828. I’m not sure exactly where Robert would have served, but in any case, he was back in England by sometime around 1831 at age 24.

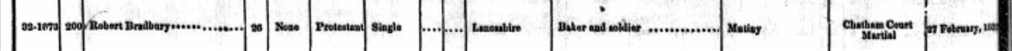

Things were about to change drastically in Robert’s life. On February 27, 1832, at age 25, Robert was convicted at a Court Martial in Chatham, Kent, England, on charges of mutiny and desertion. I have no details on the crime he supposedly committed, but such a serious charge would typically result in execution in the military of that time. However, he was instead sentenced to 14 years of transportation to the colony of New South Wales. I speculate that his sentence was downgraded—if one can call a 14-year transportation sentence a downgrade 😀—perhaps because he had simply left his barracks for a night on the drink, got into a fight, or committed a minor offense. The fact that it was a mutiny charge on British soil, rather than in a war zone, may have also influenced the lesser sentence. This is all supposition on my part, as more detailed records may eventually surface.

Many of the convicts sent to Australia would be considered very low-level offenders by today’s standards. These convicts were often sentenced for minor crimes that might not even result in a conviction today, such as stealing a letter or a loaf of bread. The British government saw this as a convenient way to establish a labor force in the colony of New South Wales during the early 1800s—a labor force they didn’t need to pay. Nearly all the early convicts sent to New South Wales were from poor, working-class backgrounds and could not afford legal representation. Appeals were not an option in those days.

In any case, the military, whose jurisdiction Robert Bradbury fell under, was a law unto themselves.

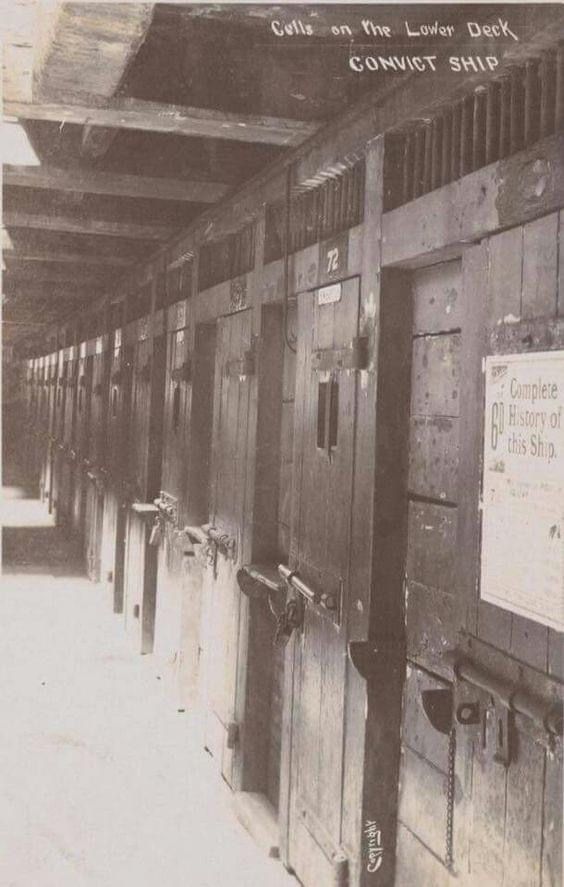

On April 27, 1832, at age 25, Robert Bradbury was transported from Portsmouth, England, along with 201 other convicts aboard the convict transportation ship Clyde (Master: Daniel N. Munro; Surgeon: George Fairfowl). The journey on a convict ship to Australia was one of the most grueling experiences of the 18th and 19th centuries. Given that Robert had previously traveled aboard ships as a soldier, he likely handled the voyage better than many of his fellow convicts. Records from this period show that conditions for soldiers and convicts on such ships were similarly harsh. The ships were crowded, with prisoners chained together amid the pungent stench of unwashed bodies, illness, and despair.

Life on board was regimented, with convicts forced to exercise on deck when the weather allowed, and meals were sparse and monotonous—usually consisting of hardtack biscuits, salted meat, peas, and oatmeal. Punishments for misconduct were severe, including flogging, solitary confinement, or ration reductions.

The mental toll was equally severe. Many convicts, disoriented by the rolling waves and sickened by the conditions, succumbed to melancholy and despair. Cramped quarters below deck offered little relief during wild storms as the ship was tossed like a cork in the Southern Ocean en route to the Great Southern Land. Food supplies dwindled, and by the time they neared their destination, fresh drinking water was rationed and often low. Many convicts didn’t survive the journey. Authorities viewed them as expendable, so those who perished simply meant fewer mouths to feed. The voyage lasted 122 days, and Roberts’s ship – Clyde arrived at Port Jackson in the colony of New South Wales on August 27, 1832.

https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/clyde/voyages/310

Convict details-

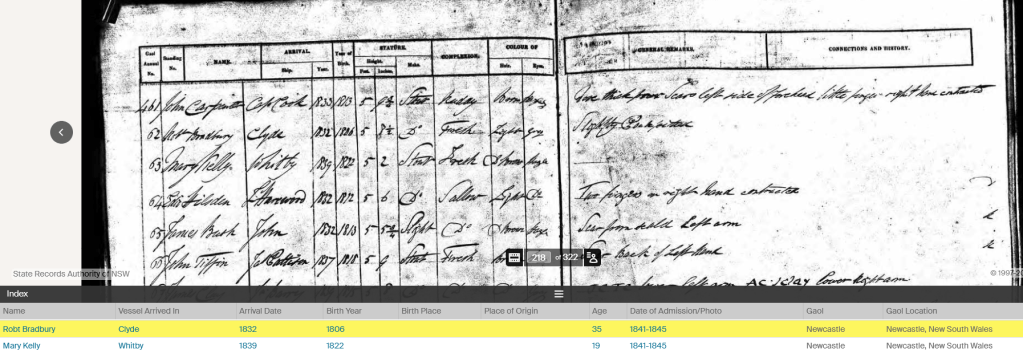

Robert was 26 years old. His religion was shown as being protestant Church of England, his complexion – fair & pockmarked, his trade was listed as a baker & soldier, his general description was 5ft 7 &3/4 inches tall, hair colour – was sandy brown, & he had lost a front tooth upper jaw, scar under the chin, a mole inside right elbow and he had neither the ability to read or write.

It is worth noting that during this period, the standard record-keeping procedure for convicts included documenting the ship they were transported on, their age, the date of arrival in the colony, and their personal descriptive details—such as height, hair and eye color, and any other distinguishing features. The rationale was to provide a thorough description in case of escape.

Records show that Robert Bradbury also had previous convictions getting him 300 lashes. Robert was, by no means a saint, having gotten into trouble & received punishment on many previous occasions.

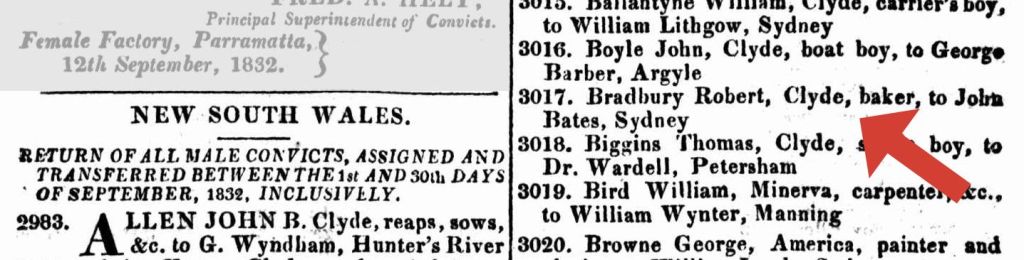

Assignment ~ September 1832 ~ Robert was assigned to work for John Bates at Sydney, Colony of N.S.W.

Residence ~ September 1832 ~ Robert lived in Sydney, Colony of N.S.W.

Occupation ~ September 1832 ~ Robert worked as a baker.

Upon arrival, as a convict he was assigned to many different free settlers around Sydney and north to around Newcastle and Maitland in NSW. He worked as a baker for publican John Bates at his Coaches & Horses Inn at Parramatta. Interestingly, he also worked as a soldier. It wasn’t uncommon for convicts to also be soldiers, working under strict supervision. As he’d already been in the Army, prior to his court martial & transportation, his military experience would have probably got him the job. Being a convict transported to Australia, in the 1800’s was no picnic. They had practically zero rights. They were sent to the colonies as punishment & that punishment was generally the harshest of hard labour. Robert Bradbury, alongside the other convicts, were moved about as needed, into the custody of a master, who controlled every aspect of their lives. If convicts dared to complain or stir up trouble, it was usually a case of going straight back into a prison. So, convicts who went to work for a master, generally tried to keep out of trouble & stay below the radar. If you kept your nose clean, there was a higher likelihood of getting a “Ticket of Leave”/Freedom. The options were then open for a former convict to get access to run a business of his own and purchase land. The backbone of our country was built on many ex-convicts who gained their freedom, and went on to run prosperous businesses, or become successful farmers.

31 December 1837 ~ Robert was recorded as working under a master, being assigned to Edward Biddulph, Maitland, Colony of N.S.W. Biddulph ran an Inn, the Crooked Billet in Newcastle, and also had land for pasture in the district, where Robert may also have worked as a shepherd.

Residence ~ 31 December 1837 ~ Robert lived in Maitland, Colony of N.S.W.

Residence ~ 11 January 1839 ~ Robert lived in Newcastle, Colony of N.S.W.

Occupation ~ 11 January 1839 ~ Robert worked as a baker and soldier.

Even at this stage of his life, in his thirties, Robert was not very good at staying out of trouble. It appears that he, like many other uneducated crooks/criminals was destined to stay in the criminal justice system.

11 January 1839 ~ Robert absconded from his assigned master, William Croasdill, Newcastle, Colony of N.S.W.

The New South Wales Government Gazette of Wed 30 Jan 1839 had an article from the Principal Superintendent of Convicts’ Office, January 29, 1839 –

THE undermentioned Prisoners having absconded from the individuals and employments set against their respective names, and some of them being at large with stolen Certificates and Tickets of Leave, all Contables and others are hereby required and commanded to use their utmost exertion in apprehending and lodging them in safe custody. Any person harbouring or employing any of the said Absentees, will be prosecuted as the law directs.

J. M’LEAN, Principal Superintendent of Convicts.

Bradbury Robert, Clyde (I), 33, Lancashire, baker and soldier, 5 feet 7 3/4 inches, fair and pockpitted comp., sandy brown hair, grey to blue eyes, lost a front tooth of upper jaw, scar under chin, mole inside right elbow, from William Croasdill, Newcastle, since January 11th 1639.

THOMAS RYAN, Chief Clerk.

The New South Wales Government Gazette Wed 6 Feb 1839 Notices show –

LIST OF RUNAWAYS APPREHENDED DURING THE LAST WEEK.

Bradbury Robert, Clyde (1), William Croasdill, Newcastle.

THOMAS RYAN, Chief Clerk.

February 1839 ~ Robert was apprehended during the first week of February. So, Robert’s time of freedom, was limited to only about a month before he was caught again

Robert Bradbury was eventually sentenced to an additional 4 years in custody. By the looks of things, it was to be served concurrently with his existing incarceration, so it looks like he may have dodged a bullet with his sentencing.

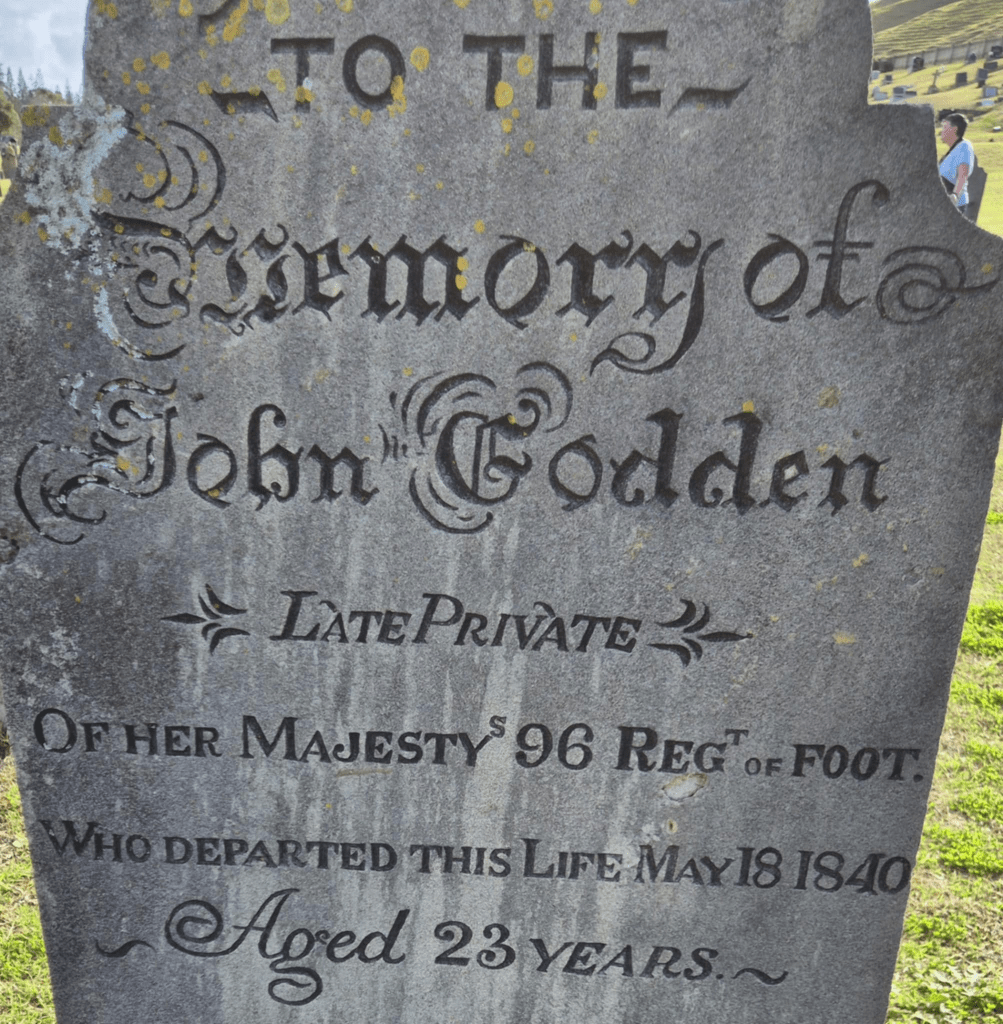

SIDE NOTE With a touch of irony that Robert would probably have been totally unaware of, in December 1839 his old regiment prior to his court marshall & transportation in 1832, the 96th, had moved to Salford Barracks in England, and later in the year to Chatham where on 4th July the first detachments for New South Wales had commenced their journey escorting convicts. This continued until 15 August 1841. My wife & I were holidaying recently on Norfolk Island, and we noticed that the 96th Regiment was also assigned to guard convicts during their deployment there. Some members of the regiment died on the island from natural causes.

The regiment was stationed on Norfolk Island to perform garrison duties, maintain order, guard the convicts, and protect the island’s interests—particularly its valuable timber resources.

The 96th Foot Regiment played a vital role in maintaining the convict system and ensuring the colony’s security during the period of transportation.

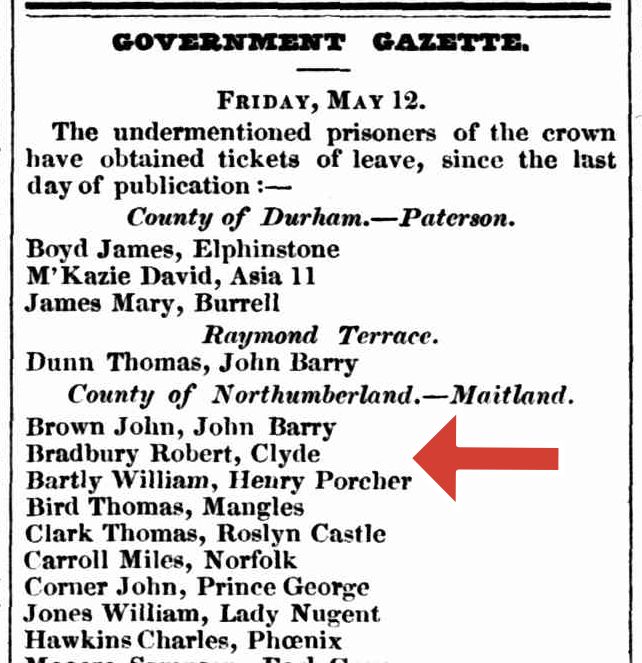

Meanwhile, back in New South Wales, entirely oblivious to the happenings of his former regiment, by 9 May 1843 ~ Robert was granted a Ticket of Leave at Maitland, Colony of N.S.W.

From 1811 convicts had to serve a minimum sentence before a ticket of leave would be granted. Once a convict had his or her ticket of leave they were allowed to work for themselves, marry, or to bring their families to Australia. However, tickets of leave did have conditions attached. They had to be renewed yearly, carried at all times and Ticket-of-Leave men, as they were known, were also expected to regularly attend religious services. They were not allowed to carry firearms or leave the colony. Once the sentence was completed, or in the case of a life sentence when a sufficient length had been served, the convict would be granted a pardon, either conditional or absolute. Ticket-of-leave men were cheap labour and convenient targets. They worked harder, complained less, and knew that refusing unfair wages or excessive work might be called “misconduct.” Although they were well on their way to freedom, conditions were attached & those conditions were strict & had severe repercussions if broken.

Unfortunately, Robert just couldn’t seem to stay out of trouble—or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that trouble had a way of finding him.

Arrested ~ 12 June 1843 ~ Robert was arrested at Maitland, Colony of N.S.W., for house breaking, he was in Newcastle Gaol awaiting trial.

Court Appearance ~ 13 July 1843 ~ Robert appeared at the Court of Quarter Sessions, Maitland, Colony of N.S.W., on a charge of assault upon James Barry, at Maitland, on the 6th June last. The jury returned a verdict of not guilty, and the prisoner was discharged.

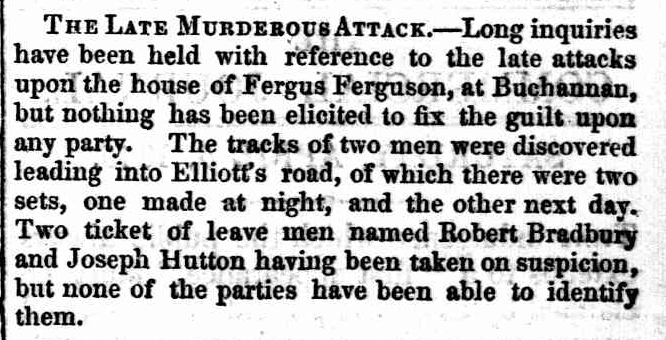

Police enquiry ~ March 1845 ~ Robert was questioned on suspicion of murder, but none of the parties have been able to identify him at Buchanan, Colony of N.S.W.

By this stage, I’m guessing the patience of the powers that be had been severely tested with Robert. He was likely quite fortunate not to have ended up on Norfolk Island, Moreton Bay, or Port Arthur, which were notorious as some of the strictest and harshest penal settlements in the British Empire at the time. Only the worst and most troublesome offenders were sent there, and Robert had accumulated a fairly lengthy rap sheet. He had been in and out of trouble on multiple occasions, facing charges of housebreaking, assault, and even a possible murder charge. These cases were eventually dropped due to lack of evidence before they went to trial.

It seems the convict administrators decided to send him far enough away in an attempt to keep him out of further trouble. Ten years earlier, Robert Bradbury would likely have been sent straight back to jail. However, by this time, the colonial government was more focused on keeping convicts out of prison and placing them in gainful employment. The colony was in need of workers—men who would earn wages and contribute to the burgeoning economy of early Australia.

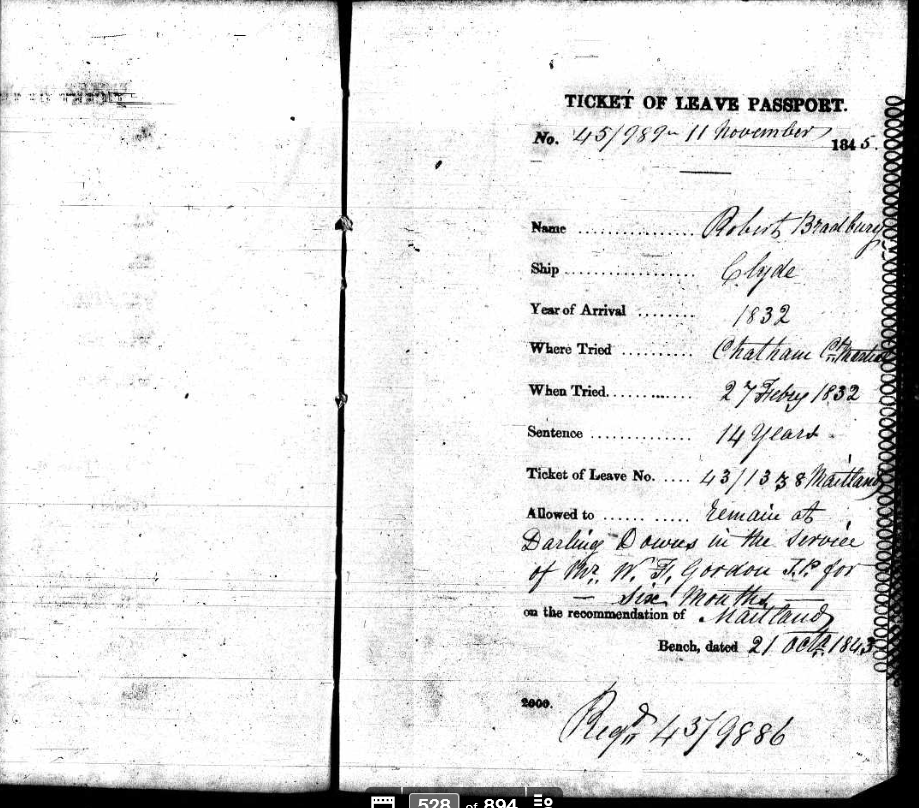

On November 11, 1845, Robert was once again granted a Ticket of Leave Passport, this time allowing him to remain in the service of W. F. Gordon for six months at Darling Downs in the Colony of New South Wales.

Unlike a Certificate of Freedom, the ticket did not end a sentence. Unlike a Conditional Pardon, it did not release a lifer from the colony’s grip. Unlike an Absolute Pardon, it offered no return home. It was parole in everything but name, earned slowly, lost instantly, lived cautiously. The colony called it mercy.

The men who carried it knew better. They lived between punishment and hope, watched by everyone, protected by no one, surviving on a single piece of paper folded into their coat, proof that they were trusted today, and could be untrusted tomorrow.

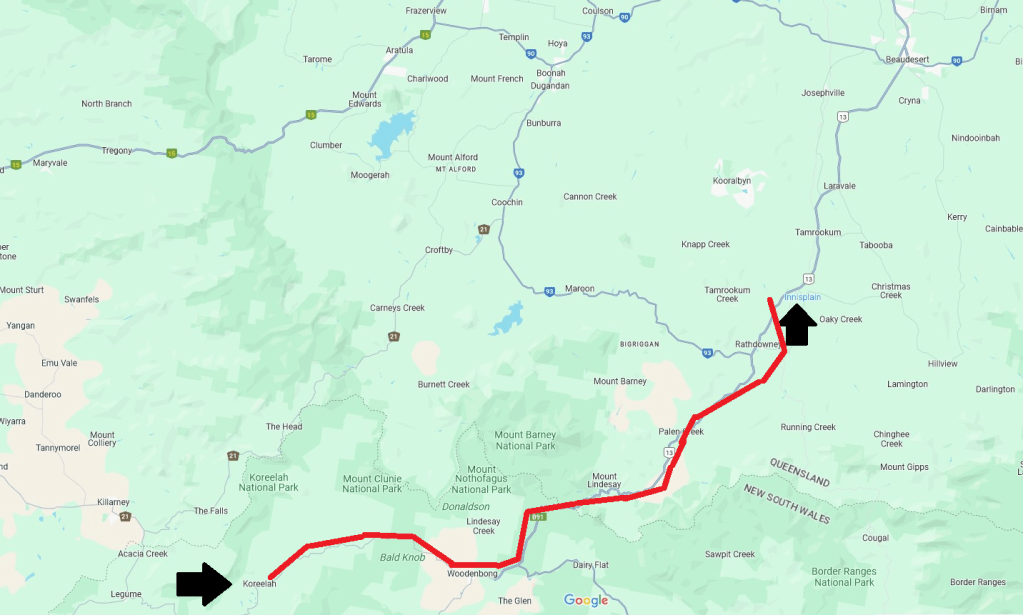

Being granted a Ticket of Leave Passport meant that he was basically delivered an ultimatum. He was sent to work as a shepherd at Koreelah Station, approx 650 klms north to the Darling Downs. That area would have had very few white settlers living there at the time. I think that the administrators were dangling the carrot of potential freedom in front of him if he could behave himself.

No.: 45/989 – 11 November 1845 – Name: Robert Bradbury – Ship: Clyde – Year of Arrival: 1832 – Where Tried: Chatham Ct. Martial – When Tried: 27 Febry 1832 – Sentence: 14 Years – Ticket of Leave No.: 42/1338 Maitland – Allowed to: Remain at Darling Downs in the service of Mr. W. F. Gordon J.P. for six months – on the recommendation of: Maitland – Bench, dated: 21 Octr. 1843 – 2000: Regd. 43/9886.

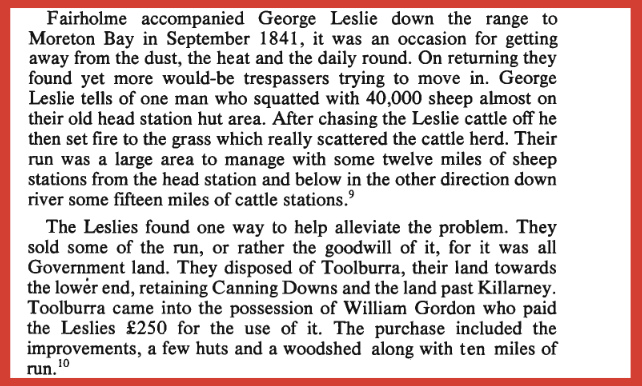

SIDE NOTE…..Some history of that particular area - The Leslie Brothers (Partrick, Walter & George), who were early settlers on the Darling Downs, found one way to help alleviate a problem, that they found himself embroiled in. Late-comer-squatters had started to trespass on to his stock runs . The Leslie’s sold some of the run, or rather the goodwill of it, for it was all Government land. They disposed of land towards the lower end past Killarney, retaining Canning Downs. The land past Killarney (Koreelah) came into the possession of William Francis Gordon who paid the Leslies £250 for the use of it. The purchase included the improvements, a few huts and a woodshed along with ten miles of run. Along with the original run owners there was also those who served as labourers, first a few convicts, then ticket-of-leave men, then the free settler labourers.

One of those “ticket of leave” men was my great/great grandfather Robert Bradbury.

Living and working in solitude, as a shepherd on a station property, or even with a few local aboriginal laborers/shepherds usually meant that there was no opportunity to get into any strife. Robert Bradbury was finally issued his Certificate of Freedom on 16th September 1846 while working at Koreelah Station on the Southern Darling Downs close to where the border between Queensland & New South Wales is now located.

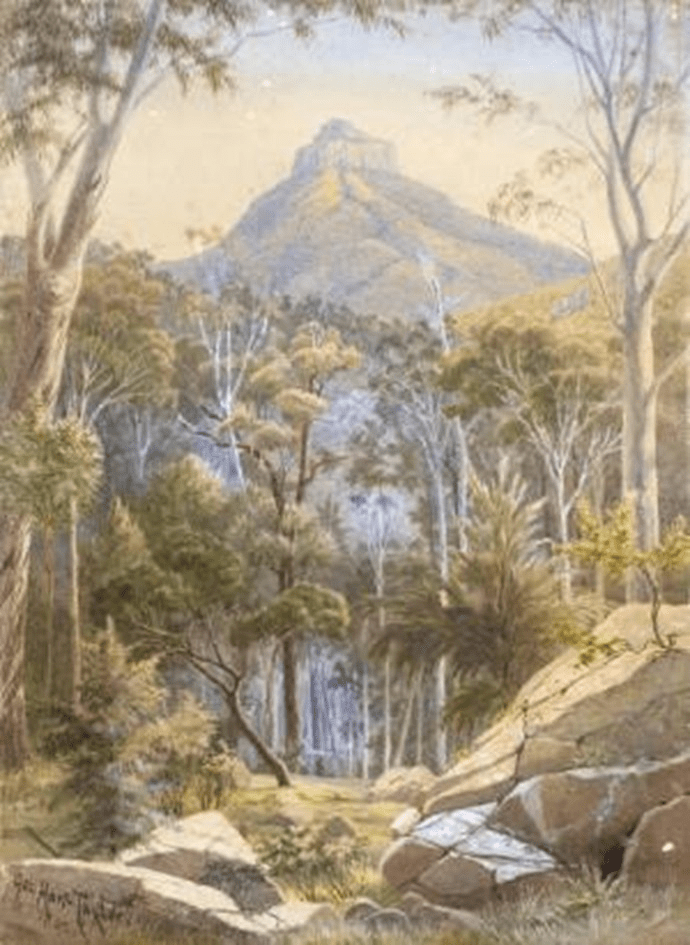

This area, on the western side of the Great Dividing Range, is where the headwaters of the Condamine River originate. The Condamine is a tributary whose waters flow into the Darling River that flows for 2800 km down the inland region of Australia, across four states – Queensland, New South Wales,Victoria, South Australia, forming the mighty Murray/Darling river system, which irrigates 40% of crops currently (2023) grown in Australia. One mountain ridge apart, on the Eastern side of the Great Divide, is the headwaters of Teviot Brook, that flows downstream into the Logan River & into the Pacific Ocean south of Brisbane. For that reason, the district adjacent to where Koreelah is located is called The Head. From this area, on the lofty heights of the main range, where he would have been mustering sheep & cattle on the station run, Robert Bradbury would have had no trouble seeing the rich flat grazing plains below the range, east to Innisplains & the small town of Beaudesert.

He would have no doubt yearned for ditching his convict existance of the last decade and a half, & returning to a normal lifestyle. Keep in mind, Robert had been a convict since he had been transported to Australia, which eventually worked out to be a quarter of his lifetime. The wheels in motion for publishing convicts new found freedom turned very slowly, as can be seen from the newspaper story above, published over a year after his certificate was issued. Needless to say, I am thinking Robert would have just wanted to get back to civilisation as soon as possible, to have a normal life, to have gainful employment, to have friends, maybe get married & to have a roof over his head that wasn’t a jail. Back then, this part of the country was still included in the colony of New South Wales. Queensland didn’t become a colony or state in its own right until 1859. Koreelah Station was eventually sold off in an estate auction to George Fairholme & the Leith-Hay brothers (William & James), but the name “Koreelah” is still kept as the district & national park name. On the 3rd of July 1847, Robert’s occupation was still listed as a shepherd at “Koreelah Station”, south of Killarney (W F Gordon’s stock run), on the southern Darling Downs. Well before its sale Robert had left Koreelah, and made his way over the Great Dividing Range on a rough track adjacent to “The Head” (used by local indiginous people), where he found employment at Henry Wilks Telemon station, Innisplain near Beaudesert, which as the crow flies, is only about 40 klms from Koreelah. The rough track he followed would much later, become “The Head Road” linking Killarney on the Southern Darling Downs, to the Fassifern Valley on the eastern side of the Great Dividing Range. Robert Bradbury would not have known it at the time, but he was crossing the Main Range where the future border between New South Wales & Queensland states is located. He was now a free man & about to become a QUEENSLANDER.

For the next few years, from about 1847, Robert lived and worked at Telemon Station Innisplain, near Beaudesert, after gaining his freedom. For the first time in a couple of decades, since his convict transportation, he was now earning money & was no doubt enjoying life as a free man. I figure that with his recent freedom, and being able to travel with the restrictions of being a convict now being lifted, he would have relished the idea of getting to meet and interact with more people, and of course, the ability to now get into a relationship, without all his movements being monitored.

Brisbane had only recently (in 1842) been opened to free settlers, but for someone like Robert, it didn’t offer many employment prospects. However as a shepherd/stockman, newer outlying towns like Ipswich, which was developing as a regional center supporting the growing agricultural and grazing industries, suited Robert Bradbury’s needs perfectly.

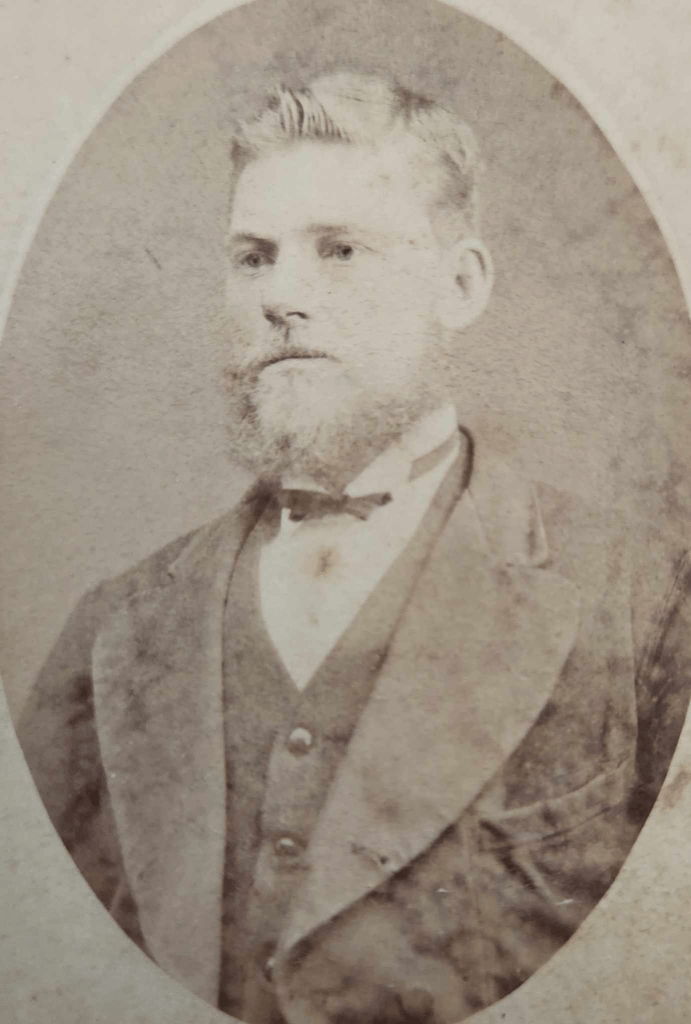

How Robert met his future wife, 18-year-old Irish immigrant Catherine Ryan, who arrived in Australia as an assisted immigrant, remains somewhat of a mystery. Catherine may have been part of the domestic staff at Telemon Station, where Robert was working, or they may have met during one of Robert’s occasional trips to Ipswich. Throughout his earlier life as a soldier, low-level criminal, and convict, Robert had never exhibited any Christian values. However, by the time he married Catherine, he had seemingly abandoned his Protestant Church of England background and converted to Catholicism, likely for the sake of the marriage. The Catholic Church generally did not welcome Protestant outsiders into its fold.

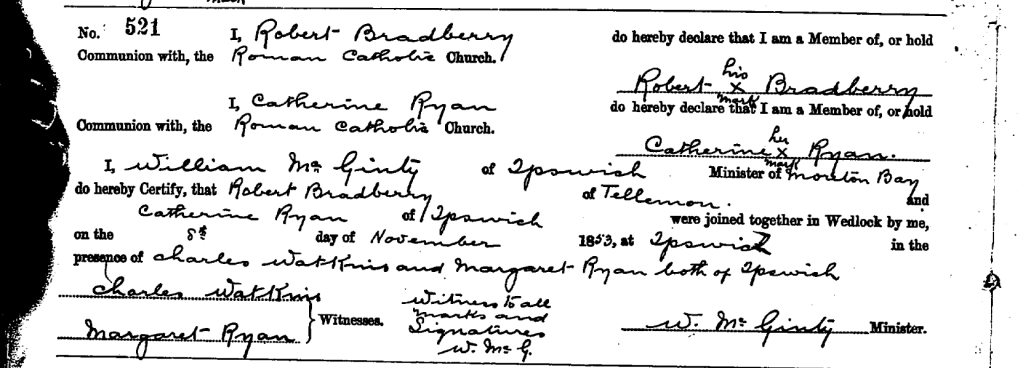

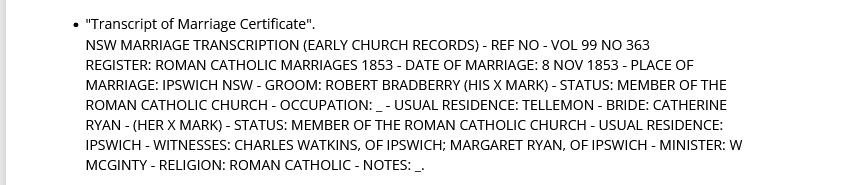

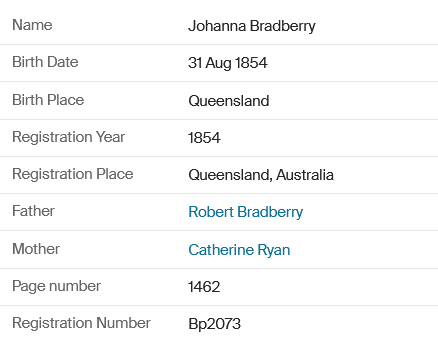

Robert Bradbury (46) and Catherine Ryan (19) were married at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Ipswich on November 8, 1853. There was a considerable age difference between the couple. Was Catherine with child at the time of their marriage? Their first child, a daughter, Johanna (my great grandmother) was born in August of the following year. In modern times, this might seem irrelevant, but in the historical context of the period, it was a serious issue given the strong Catholic beliefs Catherine held.

As a 46-year-old ex-soldier and convict, Robert probably didn’t care much about societal expectations, but as a recently freed man, he wasn’t about to let this opportunity slip past him. I’m not suggesting for a moment that there was anything untoward or sinister in Robert’s motives. However, as a recently freed convict—who, let’s face it, had likely not experienced any meaningful relationships for quite some time—he certainly wouldn’t have let a young woman with whom he had recently formed a relationship, however informal, slip from his grasp. As a ticket-of-leave man, with not much going for him, a man in his position wasn’t going to let that happen.

There was also the reality of how society viewed convicts who had been freed into Queensland at the time. Catherine, as an Irish workhouse immigrant orphan, belonged to a demographic that, like the ex-convicts, was treated poorly and held in low regard. Consequently, both ex-convicts and orphan girls found solace in each other’s company.

Sidenote….As far as I know, the Bride – Catherine Ryan & the witness – Margaret Ryan weren’t related.

By early 1854, the newlyweds were living at Laidley, in the Lockyer Valley with Robert working as a shepherd/farm labourer around the district. From the 1850s, the Laidley area was being cleared for sheep grazing.

They had their first child, a girl –Johanna (my great grandmother) who was born 31st August 1854 at Laidley, west of Ipswich. They eventually had three children – Johanna, Robert & Mary Ann, during their marriage, but also lost a couple of babies at birth.

Birth & death of unnamed Bradbury baby (1856) Moreton Bay, colony of New South Wales.

By December 1857, Robert had moved back to the Ipswich area & his occupation was listed as a shepherd/farm laborer. This move may have been partly due to the upcoming arrival of a new member of the family.

Birth of son Robert Bradbury jnr (14th December 1857 – 1934) Ipswich, colony of New South Wales.

Queensland was the name given to the new colony on the 6th June 1859

On 22nd July 1859, Robert & Catherine Bradbury lived in Ipswich Queensland. His occupation was again listed as a shepherd.

Birth of daughter Mary Ann Bradbury (22nd July1859 – 1893), colony of Queensland.

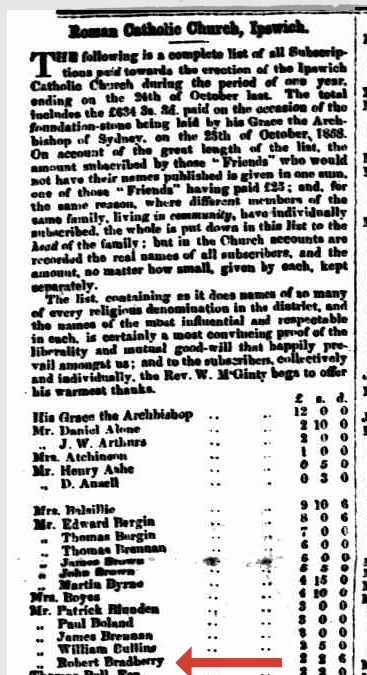

In October, 1859 Robert donated £2 2s. 6d (approx $250.00 in todays money) to a collection for the construction of St Mary’s Catholic Church in Ipswich, so he was certainly making an attempt towards a more law abiding & charitable way of life.

Robert appears to have obtained work wherever he could as a farm labourer or shepherd around the West Moreton district throughout his married life.

Birth and death of unamed Bradbury(1861–1861) Ipswich region, colony of Queensland

Sadly, Robert Bradbury died on 9 October 1862 at Bigge’s Camp (Grandchester). He had lived roughly 16 years after gaining his freedom. His death was apparently from a severe cold lasting six days (more than likely, influenza), and he was buried at Ipswich cemetery in the Catholic section. The death certificate shows his age as 50, although I have him at age 55. His wife Catherine Bradbury, with their three kids, Johanna(8), Robert(5) & Mary Ann(3) continued to live in a house at Clay Street Ipswich, for at least another ten years. She then moved to Toowoomba where she lived for approximately 30 years. Due to failing health, she then moved in with her daughter & son in law, Johanna & Nicholas Corcoran, at their farm at Moogerah in the Fassifern Valley.

Link to the Catherine Bradbury (Ryan) story here https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/05/01/catherine-ryan/

Will/Estate ~ 4 October 1881 ~ Robert’s will was granted probate; Goods, Chattels, Credits and Effects to Catherine BRADBURY.

As with any ancestry research, times, dates and ages can easily become muddled. It usually comes down to cracking the code and finding one simple record of a time and a place that has been recorded, and trying to match it up with whatever other details are available. Many of our very early pioneers were illiterate. They didn’t keep any of their own records. Photography was pretty much nonexistent until the mid to late 1800s. The only details on them were usually immigration arrivals, and any local records of land purchases, rate notices, births, deaths & marriages. If they broke any laws and were recorded going through the justice system at the time, they may have made it into the newspapers of the day. If you were a law-abiding citizen, you went through life with very little record of your existence other than birth, marriage, and death records being kept. It shouldn’t come as any surprise that the convicts probably had more records kept on them than any of the free settlers. Hence, the records about Robert Bradbury were quite detailed up to the point, of him gaining his freedom.

What happened to Robert & Catherine Bradbury’s children?

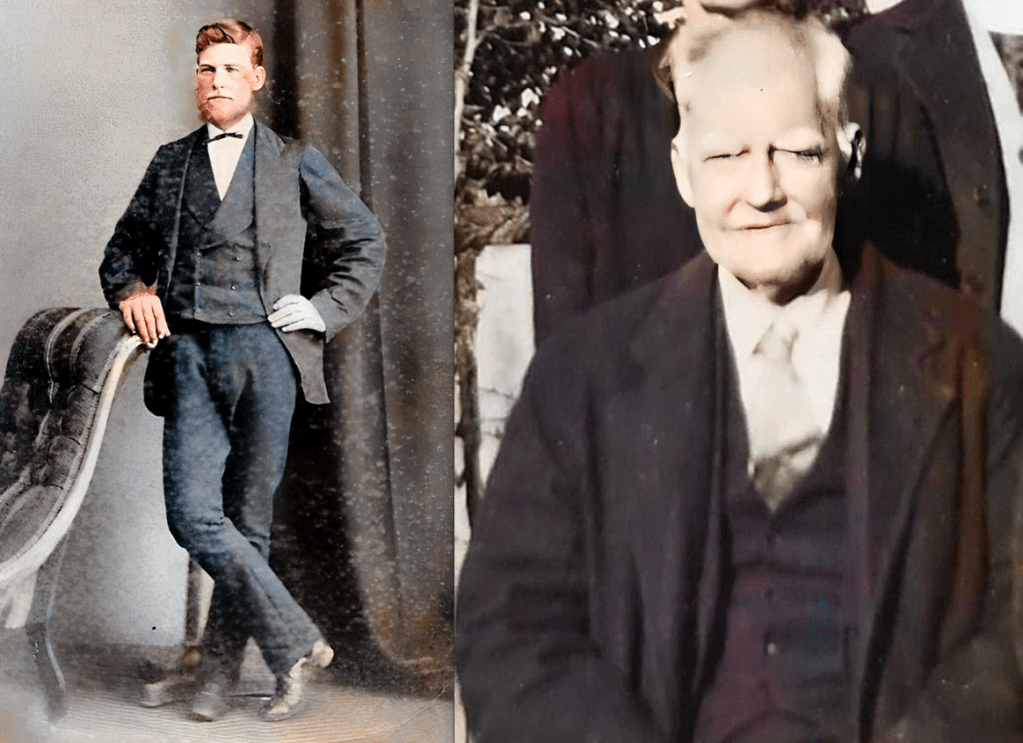

Son, Robert Jnr married Matilda Christina Albertine Discher. & lived in Mackay.

Daughter, Mary Ann, married Charles Thomas Regan. They also lived in Mackay.

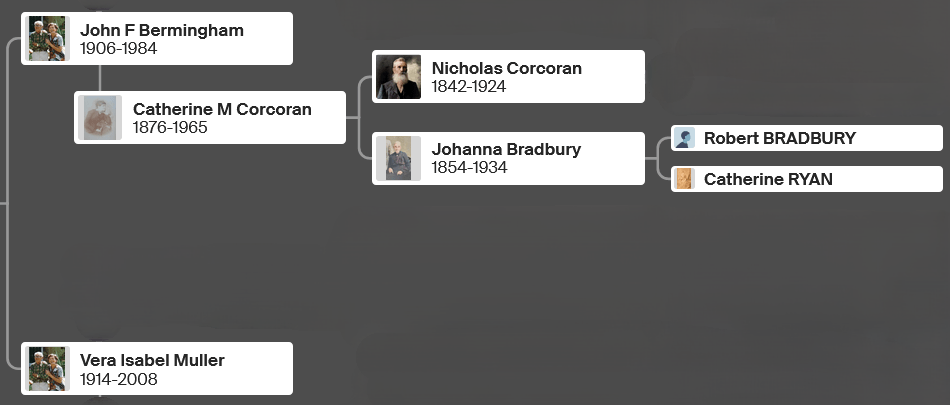

Their oldest child, daughter Johanna Bradbury (my great Grandmother) married a farmer & grazier, Nicholas Corcoran (my great Grandfather). They had eleven kids and lived at Fassifern Valley. Johanna & Nicholas’s daughter, Catherine Mary Corcoran (my grandmother) married Edward Bermingham (my grandfather).

So, according to what I have found on Robert Bradbury’s life, he appeared to have settled down from his earlier turbulant existence, after he was married & had a family to support. In saying that, Robert Bradbury born 1806 St Helens Lancashire England, grew up in England & served in the British armed forces, charged with desertion, convicted & transported to Sydney Australia in 1832 aged 25, gained his freedom in 1846 aged 39, married 1853 aged 46, sadly died in 1862 Bigges Camp (Grandchester Qld) at the relatively young age of 55 leaving his wife Catherine with three young kids. He finally got his freedom but didn’t live long enough into his later years to enjoy it.

In closing this story on my great great grandfather Robert Bradbury, it is worth noting the situation relating to how our convict ancestors were treated, not only from the brutal masters, but also from their families & descendants.

I have sighted many documents & records showing that there was a considerable amount of shame held by family members, back in the day. Apparently, some but not all, didn’t want it to become public knowledge that their father or mother was a convict.

However, in modern times, having a convict ancestor is a much cherished part of many peoples family history. We appreciate it & wear it like a badge of honour. How times have changed!

Robert Bradbury’s life journey – Born 1806 Manchester England, c1822 Enlisted as a soldier, Manchester – Spain – Nova Scotia – Bermuda – Nova Scotia -Chatham England. 1832 Court Marshalled & Transported to New South Wales as a convict. 1847 Freedom. Died 1862 Bigges Camp (Grandchester) Queensland.

Geoff Bermingham