Reading time 32 minutes

I decided to write this blog installment about my family ancestors to clarify a few points, share the trials and tribulations of their story—as well as mine, in trying to trace their journey—and offer advice to help others get started. Although I’ve got to admit tracking all of them & making many mistakes along the way is one of the most enthralling parts of the whole exercise. Beginning the journey into ancestry research is often the hardest part. As genealogy enthusiasts, we’ve all faced that initial challenge: Who do I choose to start with & where do I begin?

As a novice, I felt overwhelmed. Should I start by tracking down long-lost living relatives I hadn’t seen in years? Would they be willing to talk to me or share any records they had? The whole process seemed daunting at first. After a lot of aimless searching without a clear direction, I finally took the plunge and joined an ancestry group. In my case, it was Ancestry.com—but more on ancestry groups later.

Joining the group was a great decision. Before long, people started reaching out to me, and I realized that we are all in this together. For most, genealogy begins as a simple mission to build a family tree. But as I delved deeper, I uncovered fascinating details about my ancestors’ lifestyles, environmental circumstances, political views, religious beliefs, and other aspects of their personal lives.

While the genealogy part of the process was relatively straightforward, I soon moved beyond just names and dates. I became completely absorbed in understanding the lives they led and the world they inhabited.

Initially, I thought it would be nearly impossible to understand their personalities, since I had only known three of my four grandparents. Yet, when you start digging, it’s incredible what you can discover. It reaches a point where you can even discern their personal traits and quirky characteristics, gaining insight into what they were like.

As I began uncovering more information, I realized that I wanted to see my ancestors as they truly were. Some had difficult or flawed personalities; some were simply hard to get along with. Yet, most seemed to be kind and genuine people who came to Australia seeking a better life for themselves and their families.

Along the way, I discovered both the sorrowful and joyful chapters of their lives—the hardships they endured as well as the successes and happiness they found. The stories told in eulogies often don’t present a complete or accurate picture of a person’s life. I wanted to capture their stories honestly—warts and all.

While collecting and organizing my family’s ancestry, I noticed how a small number of people present themselves as if they single-handedly uncovered every detail. They project an image of being the ultimate authority on family records. Too often, they attach their names to an ancestor’s story and claim some sort of ownership of the records, as though they were the original discoverers. Thankfully, this doesn’t happen very often, but there are certainly a few who insist on portraying themselves as the definitive source of knowledge.

In reality, almost everyone—including myself—is simply casting a net and gathering information from websites and family sources, which themselves draw from libraries and archives preserved for centuries. I have never claimed, nor do I intend to claim, that my work is original. The truth is that the internet has made research dramatically easier for all of us.

So, please don’t take credit for research that was done long before you. Like me, you have simply copied, compiled, and arranged details, records, and photographs to build your family’s story.

Here in Australia, we are fortunate to have access to some incredible resources for researching our ancestors. At this point, I’ll mention just one of them. In addition to the many dedicated ancestry websites, the National Library of Australia operates Trove—a free online resource and digital library. Trove serves as a central access point to a wide range of digital collections from across Australia, including those from libraries, museums, galleries, and other institutions.

One of Trove’s most valuable features is its expansive archive of historical newspapers, which continues to grow. These archives provide invaluable insights into the past and can be instrumental in genealogy research.

Beyond the local websites in Australia, internet access has opened doors to a vast number of archives and genealogy websites across the world. Personally, I’ve been able to explore old Irish birth, death, marriage & famine records, as well as historical archives from both Germany and Ireland.

There are now thousands of archives and museums worldwide, available online, significantly simplifying the research process for amateur historians like us.

In tracing our family’s ancestry, I realized that I was, in one sense, extremely fortunate. Nearly all of our ancestors came from Ireland and Germany, with only one originating elsewhere—England.

Early in my research, I discovered that Ireland had very little recorded information from before the potato famine of the mid-1800s. For reasons I will explain shortly, historical records from earlier periods are scarce for much of the Catholic population of that era. Germany, on the other hand, proved to be the opposite—offering a relative treasure trove of well-preserved records spanning centuries.

With these pieces of the puzzle as a starting point in the Australian context of our ancestors’ story, where do we begin?

The East Coast of Australia was mapped in detail by Captain James Cook in 1770, and the first British settlement began in 1788 with the arrival of the First Fleet. To keep the story focused, we’ll set aside earlier visits by the Dutch, French, Portuguese, and Spanish explorers.

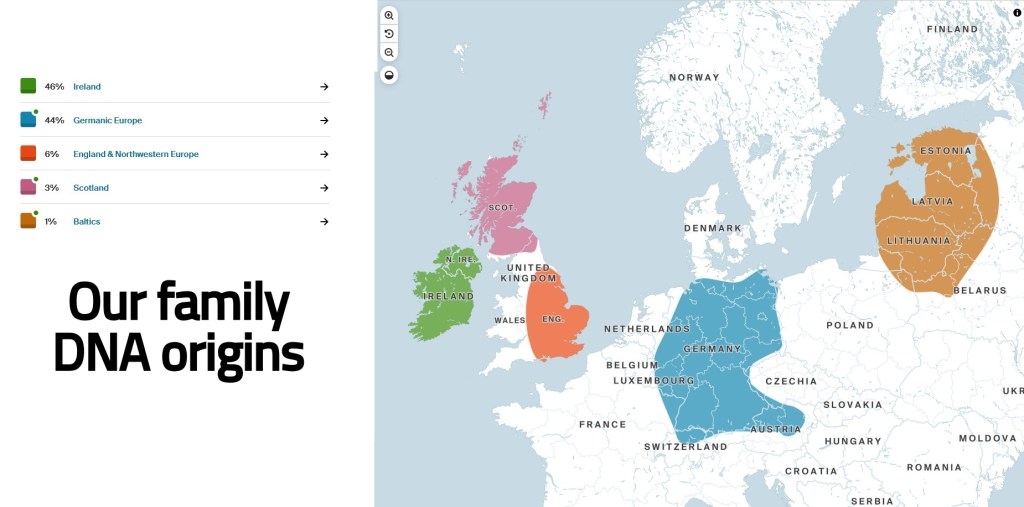

My Ancestry DNA results indicate that I am 46% Irish and 44% German, with the remaining 10% tracing back – to England -6%, Scotland -3%, and the Baltic region -1%. Based on my research into historical DNA patterns, these smaller percentages may reflect ancestral migration across Europe that occurred centuries ago & eventually ended up in either Ireland or Germany.

Why Australia? My Ancestors’ Decision to Leave Home

The reasons they chose to travel across the world almost always came back to the same point. Their countries and regions were caught between warfare, poverty, famine, and political turmoil. At the time, deciding to leave their homeland was much like us today choosing to live on another planet. They had no idea what awaited them, or even whether they would arrive safely. When considering Australia as a destination, both the Irish and the Germans were influenced by delegations from Queensland that visited their countries to promote migration. These delegations offered conditional free land to farmers, which was an irresistible opportunity. Many people in Ireland and Germany had nothing, so the chance to own freehold land in a new country provided a solution to their hardships. Beyond material prospects, the promise of religious and political freedom, along with the opportunity to start anew, made Australia’s offer highly appealing.

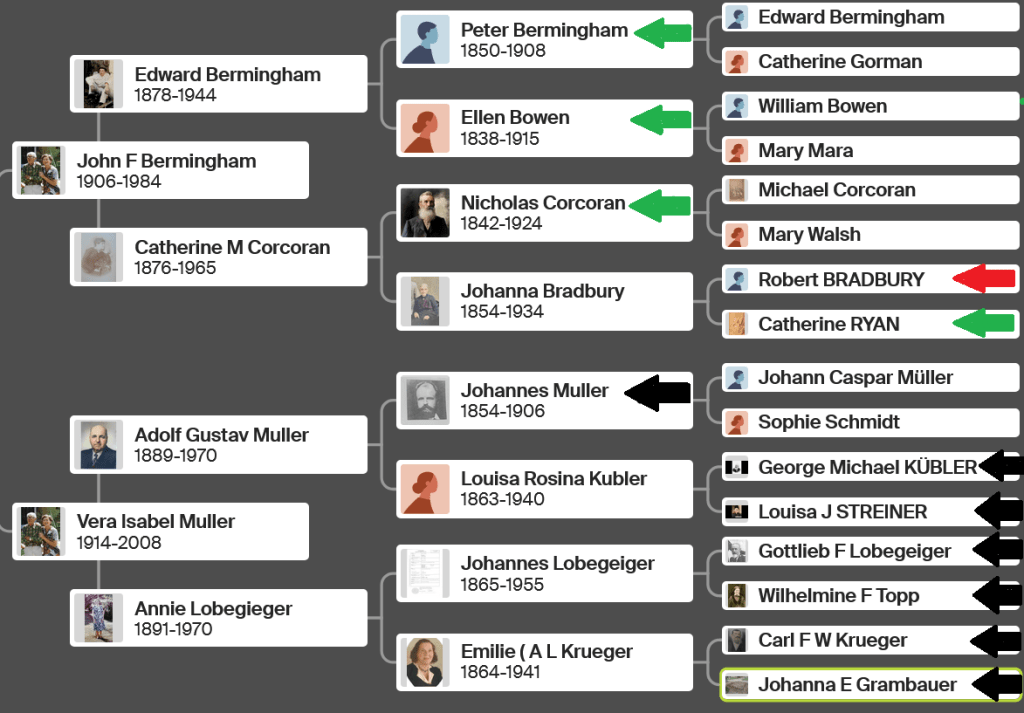

The first of my ancestors to arrive in Australia were my great-great-grandfather Robert Bradbury (born in England in 1806), a convict who landed in Sydney in 1832, and my great-great-grandmother Catherine Ryan (born c1834), who arrived in Brisbane in 1852 as an assisted immigrant from Ireland. Although they arrived in Australia two decades apart, their paths eventually crossed, and they married in 1853 in Ipswich, Queensland. The rest of my ancestors, all Irish and German, arrived in Queensland in the second half of the 19th century. I have included a link to each of our family’s immigrant ancestors below.

THE IRISH IMMIGRANTS ☘️🇮🇪

Catherine Ryan – Tipperary (arrived Brisbane Queensland 10-8-1852) on board the “Meridian” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/05/01/catherine-ryan/

Ellen Dunn (Bowen) – Nenagh Tipperary (arrived Brisbane Queensland 12-10-1856) on the “Lady McDonald” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/03/04/ellen-bermingham-dunn-bowen/

Nicholas Corcoran – Danesfort Kilkenny (arrived Brisbane Queensland 12-11-1864) on the ship “Hannemore” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/11/26/nicholas-johanna-corcoran/

Peter Bermingham – Carbury Kildare (arrived Maryborough Queensland 9-10-1874) on the ship “Great Queensland” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/02/22/peter-bermingham/

THE GERMAN IMMIGRANTS 🇩🇪

George M Kubler, Louisa J Streiner – Biberach, Baden Werttemberg (arrived Brisbane Queensland 14-9-1863) on the ship “Beausite” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/04/22/george-louisa-kubler/

Gottleib F Lobegeiger, Wilhelmine F Topp -Templin, Brandenburg (arrived Brisbane Queensland 17-1-1864) on the ship “Suzanne Goddefroy” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/04/13/gottlieb-frederich-ferdinand-jeleb-lobegeiger/

Carl F W Krueger, Johanna E Grambauer – Pinnow, Brandenburg (arrived Brisbane Queensland 6-9-1865) on the ship “Suzanne Goddefroy” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/04/04/carl-johanna-krueger-emilie-albertine-louise-lobergeigerannie-muller-vera-bermingham/

Johannes Muller – Tuttlingen, Baden Werttemberg (arrived Brisbane Queensland 7-2-1879) on the ship “Fritz Reuter” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/02/03/johannes-john-muller/

OUR CONVICT ANCESTOR 🏴

Robert Bradbury – St Helens, Lancashire (arrived Sydney New South Wales 27-8-1832) on the ship “Clyde” https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/11/08/robert-bradbury-2/

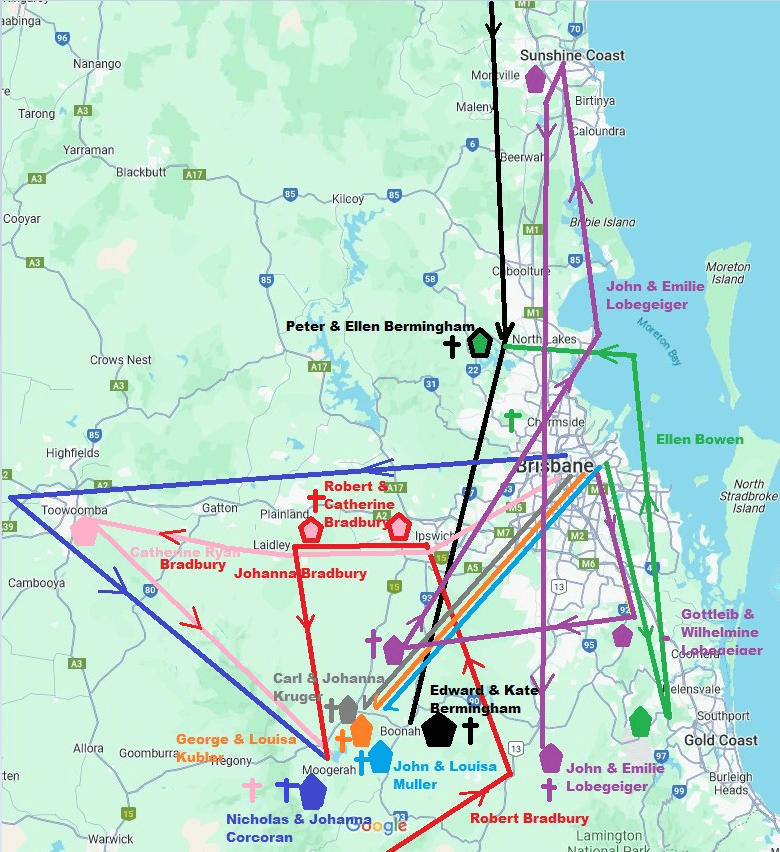

Family pathways our ancestors made on arrival in Australia. Robert Bradbury a convict transported to Australia for desertion was the first to arrive in 1832, coming up from Sydney. His future wife, Catherine Ryan arrived in Brisbane in 1852. Ellen Dunn/Bowen 1856, George & Louisa Kubler 1863, Gottleib & Wilhelmine Lobegeiger 1864, Nicholas Corcoran 1864, Carl & Johanna Krueger 1865, Peter Bermingham 1874, Johannes Muller 1879.

I’ve now written articles on most of my ancestors. When I began this ancestry journey, I hoped to discover where I came from and, perhaps, whether we had any high achievers in our family history. Many say that ancestry research is a journey of discovery, and I can certainly agree. Beyond realigning my priorities, I also learned more about myself along the way.

All of our Irish ancestors were farmers, while our German forebears were farmers or artisans. Our English lineage includes laborers and military members, though we do have a trace of nobility as early as the 15th century. Many people get excited when they discover a hint of an upper-class connection, but these ancestors were people, just like everyone else, and they didn’t contribute anything to the gene pool beyond what any other ancestors did. My wife’s family tree has a distant, tenuous connection to William Shakespeare, yet even this doesn’t feel exclusive. Over 500 years, descendants of these famous individuals could easily number in the millions, so it’s not a unique club. I haven’t completely abandoned tracing our roots back to the home countries, but I prefer to focus on the details after our ancestors arrived in Australia.

From the start, I had doubts about the accuracy of many centuries-old records from our ancestral home countries. The world has endured two World Wars and numerous other conflicts just since 1900. Prior to that, both Ireland and Germany—where my ancestors originated—suffered through wars, famines, and civil unrest over the past thousand years. Many original archives, museums, and historic records were destroyed by invasions, fires, and civil strife during these tumultuous periods, as well as during internal disputes. Consequently, the likelihood of finding detailed and accurate information about our ancestors before they arrived in Australia is significantly reduced.

The Irish records were unreliable, to say the least. Roman Catholic record-keeping was banned until the relaxation of the Penal Laws in the late 18th century. While some Catholic marriage records from the late 1700s can be found in larger towns and cities, most rural Catholic parishes in Ireland only began keeping records in the 19th century.

In ancestry circles, the term “brick wall” refers to the point in genealogical research where no further records seem to exist. Occasionally, another document surfaces, but in truth, most Irish brick walls date back to the mid-1800s—when the Irish Penal Laws were still in effect and the country remained in the grip of the Great Famine.

Remarkably, I’ve had better success tracing records on the German side of my family. Germans are known for their meticulous record-keeping, and I’ve uncovered many well-documented ancestral details. I was genuinely surprised by how many records survived, especially given that German cities and towns were heavily bombed during World War II, which destroyed countless archives and museums. Major cultural centers such as Berlin, Dresden, Cologne, Leipzig, and Munich experienced significant archival losses during the war.

On my mother’s German side, I have traced our lineage back over 500 years to Johann and Catharina Haysel, my 12th great-grandparents, who lived in the late 1400s in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. They are part of the Kubler family line.

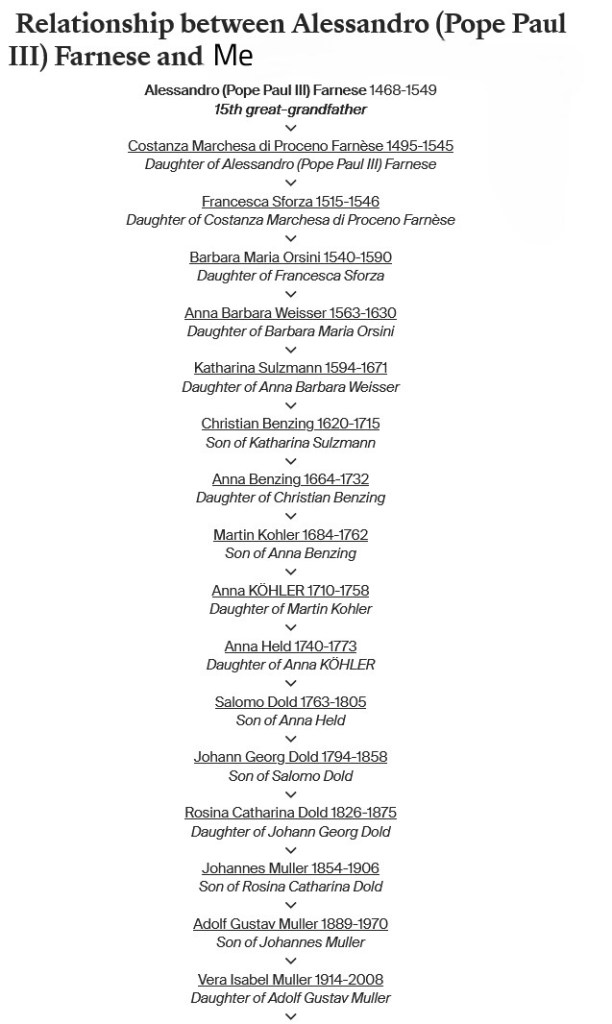

I have also discovered a connection to Alessandro Farnese (Pope Paul III), born on February 29, 1468, in Canino, Latium, in the Papal States, Italy, and who died on November 10, 1549, in Rome, Lazio. He and his mistress, Silvia Ruffini, are my 15th great-grandparents. Between approximately 1500 and 1510, they had at least four children, one of whom was Constanza Farnese. Three generations later, her descendants found their way to Germany, eventually connecting to the Dold family. Rosina Catharina Dold, my great-great-grandmother, is among their descendants.

With a touch of irony, despite earlier skepticism about claims of famous family connections, I’ve uncovered a connection to a Pope—a church leader, no less. And here I am, someone without a trace of religious belief, who holds no faith in any divine being or religious institution. You might wonder how a Catholic Pope could have had a mistress and children. In fact, several Popes were known to have had affairs, either before joining the clergy or even during their time in office. A few continued these relationships while serving as Pope. This highlights that even 550 years ago, the Catholic Church was not immune to hypocrisy—something that, given its long and complex history, may not be entirely surprising.

Commercial autosomal DNA tests are generally effective for identifying relatives within 6 to 8 generations (about 150-200 years). Beyond that, the shared segments are often too small to be reliably detected or assigned to a specific ancestor

Without overemphasizing the point, it’s worth noting that this man’s descendants & family connections now number around 250,000 (depending on how you do the Maths). He is also only one of my 65536, 15 x great-grandparents, so we aren’t getting too carried away at this discovery. So, being one of the descendants doesn’t necessarily make you closely connected to anyone of celebrity status. In fact, it has been estimated that one in four people in the UK has some form of ancestral lineage to William the Conqueror.

One person with a distant connection to William the Conqueror is my wife. As I’ve mentioned before, it’s hardly an exclusive club, but it remains fascinating nonetheless. Tracing her lineage beyond William the Conqueror led me to his own predecessors, whose records date back to around 808 AD—approximately 1,200 years ago.

It was at this point that I began to wonder how accurate these records truly were. Like millions of others around the world, we join the dots from historic documents to build our family trees—but how reliable are they?

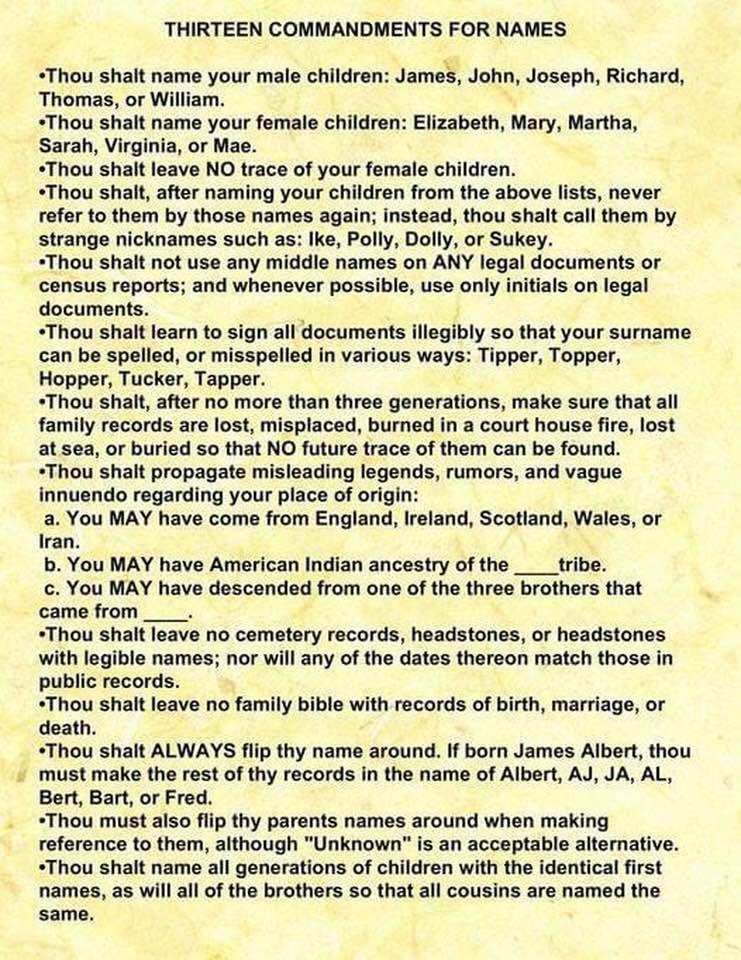

Every date and detail has been recorded, copied, and transferred over the years by humans, and humans are prone to mistakes. Even decades or centuries ago, errors could creep in—whether accidental or intentional. We strive to be thorough and preserve our history accurately, but information, whether from its original source or passed down through others, can easily alter the truth and turn family stories upside down.

My takeaway from all this is that no one can offer an ironclad guarantee that their genealogy is entirely accurate. Whether you’re an amateur historian like myself or a professional who has dedicated a lifetime to the work, mistakes still happen. Computers can help distinguish fact from error, but I still maintain a healthy degree of doubt about any records—official or unofficial—that date back more than a couple of hundred years.

My father’s Irish lineage lacks reliable records before the Great Famine of the 1840s. The oldest records on my father’s side come from a connection to England: my 15th great-grandparents, Sir Matthew Browne, MP of Betchworth (1469–1557), and Lady Fredeswith Guildford (1478–1525). These ancestors link to our only English relative, my great-great-grandfather and convict, Robert Bradbury.

Clearly, our family’s standards had slipped considerably by the time Robert arrived in Australia. 😃

That said, I’ve managed to trace our German lineage back about 500 years. Anyone who has researched a few generations knows that the ancestral lines can become a confusing maze that often fades away.

Imagine wandering through an old city or town that you’ve never been to before, with no clear sense of direction, as you attempt to find a particular location. You navigate cobbled streets and narrow laneways, climbing steep stairways in search of a clue to confirm you’re on the right path. Sometimes, you find an address, only to discover there’s nobody home. A single wrong turn can lead you completely off course, forcing you down the wrong pathway. Often, you end up at dead ends, retracing your steps and seeking a new route. Along the way, there are many clues, but not all of them can be trusted.

As previously mentioned, another lesson I learned early on is that many ancestry site members often copy and paste information from others. While copying records is integral to ancestry research, I can’t overstate the importance of fact-checking! If several people copy an incorrect detail, it can quickly be considered factual. A photo you find that you believe depicts Great Aunt Edna or Uncle Bob could actually be a completely unrelated person. Unfortunately, many old photographs were either unlabeled or mislabeled, creating a modern version of Chinese whispers. Although it’s a fascinating journey, it can also be a frustrating exercise in the search for facts.

Since the arrival of white colonization, Australia has not faced invasion by an external power—unless one considers the First Fleet’s landing in 1788 as such. Views on colonization vary widely, yet it is vital to acknowledge the acts of genocide inflicted on First Nations peoples by colonial forces. Even the word invader provokes anger and denial among many white Australians. Still, no other term adequately describes what occurred after 1788.

Modern historians are increasingly confronting these difficult truths about Australia’s early colonial history. The frontier wars in Queensland—my home state—were the bloodiest and most brutal of all, with at least 65,000 Aboriginal people killed, a figure regarded as conservative.

As I have grown older, I have come to fully grasp the horrors endured by Indigenous Australians, who saw their lands seized and their lives shattered by relentless colonial aggression. Disease, genocide, the Stolen Generations, deliberate poisoning of food and water, and sustained violence against an entire people expose how distorted the version of history I was taught in the 1960s truly was. In truth, Australia’s colonial governments proved no less ruthless than the very English and German regimes from which many of our ancestors once fled.

Up until the 1960s, Australia maintained a “White Australia” policy enshrined in federal and state legislation.

Sadly, racism still permeates modern Australian society. We all know people who harbor such views—some even hold positions in our government, public institutions, and workplaces. Many of us have family members whose views we must tolerate for the sake of family harmony. They’re the ones who dominate conversations at family gatherings, convinced their racist and regressive political beliefs are the solutions to all our national issues. Evidence, photos, and historical records mean nothing to them. In fact, racists often rely on their own distorted version of history to reinforce their beliefs and justify their perspective. They live in their own world of hate and bigotry, surrounding themselves with like-minded people. There are also the so-called “soft racists,” who take a more conservative approach. They remain quiet in public but still harbor racist views, often nodding along with louder, more outspoken individuals without openly expressing their own opinions. These are the people who silently empower far-right politicians by voting for them while avoiding any public association with that political stance. My home state of Queensland is probably the most racist in Australia; head north of the Sunshine Coast or west of the Great Dividing Range, and you’re in redneck country.

Update – In October 2024, Queensland elected an ultra-conservative right wing state government that introduced major policy changes in crime and punishment, which will primarily impact Indigenous people, likely leading to higher incarceration rates within the community. It appears that little has changed in our justice system regarding the ongoing persecution of Australia’s Indigenous population. But I digress.

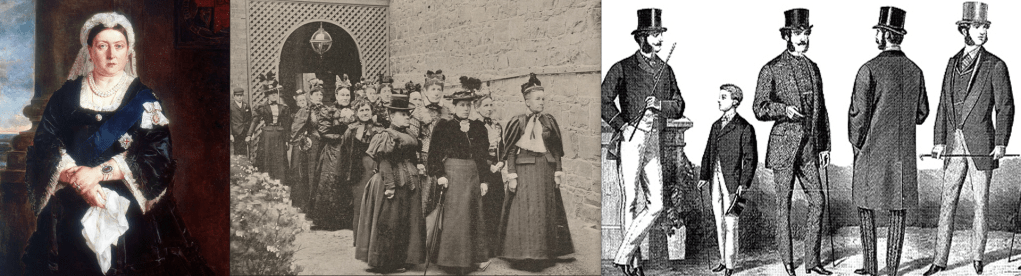

Thankfully, Australia has retained most of its historic migration records since the First Fleet’s arrival. The British colonizers were meticulous record-keepers, and newspapers began recording information from the early days of settlement. By the 1850s, photography was becoming more common, so images of people, places, and events in Australia’s history were preserved.

As a fifth-generation Queenslander, my earliest ancestral arrival was a convict, Robert Bradbury, transported in 1832 for desertion from the British Army.

As a side note, my wife’s earliest recorded ancestors to arrive in Australia had all-expenses-paid trips of a different kind: James Beckett, a convict who arrived with the Second Fleet in 1790, just 17 months after the First Fleet, and Ann Calcut, another convict from the same fleet. This makes my wife an eighth-generation Australian, descended from some of the earliest “Aussies.” James Beckett and Ann Calcut, who later married, did not choose to come to Australia; they were convicted and sentenced to transportation for life. Eventually, both were later granted their freedom, and James Beckett became a brickmaker in Parramatta. All up, in my wife’s family tree, there are records for eight convict ancestors.

Queensland’s first census was conducted on April 7, 1861, with a population of 30,059, comprising 18,121 males and 11,938 females.

My thoughts on ancestry tracing are not intended as a definitive guide. It’s just how I’ve chosen to explore my roots, having started after retiring a few years ago. While it is a time-consuming endeavor, it’s also deeply addictive. Some people have been doing this for decades. I must admit that, as kids, we used to roll our eyes when our parents, grandparents, and relatives reminisced about family history. Now that I’ve caught the genealogy bug later in life, I wish I had paid more attention back then.

Uncovering details and stories about one’s ancestors only fuels the desire to learn more. It’s an incredible educational experience that offers insights not just into my ancestors but also into their worldviews. I’ve learned about their daily tasks, generational thinking on politics and environmental issues, and how religion influenced their lives. I’ve discovered that my family’s ancestors learned early on to live within their means.

We tend to think of our ancestors as old-fashioned and set in their ways, but they, too, were young once, full of hope and enthusiasm for the future. We’ve all seen documentaries and old photos of historical figures, but when the images are of your own grandparents, great-grandparents, and other relatives, they hold a special significance. Their lives—what they saw, how they lived, and how they raised families—become deeply personal. Starting from scratch, they built farms, cleared land, and worked with basic tools. They didn’t have access to health care, reliable water, or even modern sanitation. They were incredibly resourceful, creating inventions and tools to make life on the farm more manageable. Without the hindsight we have now, they did the best they could with what they had.

Some current attitudes reflect poorly on past generations, particularly regarding racism and environmental concerns. However, people are products of their time. During the Victorian era, the British Empire, of which Australia was a part, still endorsed slavery, and colonialism brought with it brutal and unethical practices. It’s easy to criticize now, but the early settlers were merely trying to survive. Australia was called “the lucky country,” but the settlers’ success was due to hard work and persistence, not mere luck.

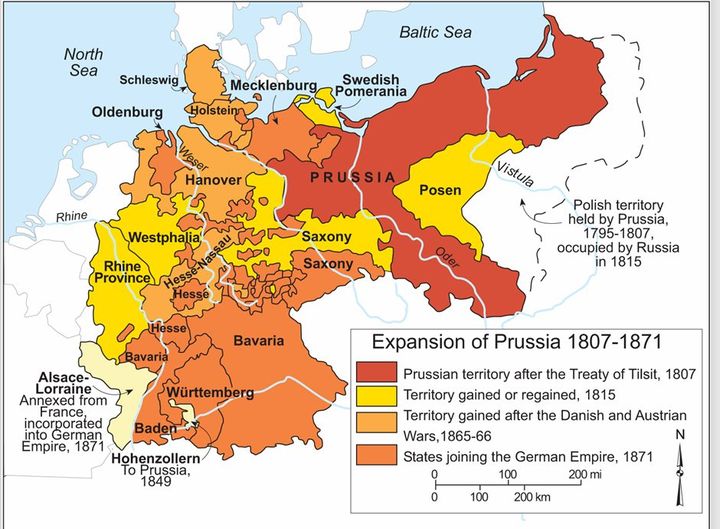

The map of Prussia (Germany) from 1807 to 1871 highlights the country’s disunity and turmoil during that period, a time when many of our ancestors emigrated in search of a better life. My family’s ancestors were among those who left to escape the instability. The various states and provinces of Prussia were in constant conflict with one another. It is no surprise that our ancestors decided to leave and make their way to a more peaceful country like Australia to start new lives.

Although colonial Australia treated First Nations and Pacific Islander people appallingly, the people of that time were shaped by their circumstances. The environment was seen as something to be exploited rather than protected. It’s only in the past 20 years that we’ve begun addressing issues like global warming seriously. Early settlers learned that by caring for the land, the land would care for them, and they embraced many environmental practices & soil preservation long before it became a global concern.

Religious beliefs also played a significant role in their lives. In colonial Australia, community ties were strong, often formed around church congregations that could be obsessive and cult-like by today’s standards. The Irish married the Irish, the Germans married the Germans, and communities were often insular, reflecting their languages and religious affiliations. The area where my family settled in Queensland—the Fassifern Valley—was divided along these lines. English settlers took the creek flats, while the Scots and Irish chose timbered country, and the Germans selected the rich soil of the Fassifern Scrub. Severe drought greeted these pioneers in the 1870s, but not one abandoned their land. They were driven by a fierce sense of ownership, pride, and resilience.

Education standards improved over time, and with greater access to newspapers and, later, radio, people became more informed about their communities and the world.

As I’ve traced my family’s history, I’ve followed leads that looked interesting but often led nowhere. I’ve come to realize that tracing ancestry isn’t only about finding captivating stories—it’s also about understanding where you come from. Discovering family history can feel like time travel, offering a fascinating look at what life was like centuries ago. How amazing it would be to meet these people from our past, to hear their reasons for coming to Australia, and to ask about life in the old country!

Our ancestors embarked on arduous journeys across the world under extremely challenging conditions. They left their homes and crossed oceans, enduring horrific hardships and risking their lives to reach Australia. Many did not survive, succumbing to disease or perishing in shipwrecks. So, next time you’re seated on an airplane—enjoying an in-flight movie, a meal, and a few relaxing beverages, or perhaps complaining about the length of the flight to your overseas destination—remember the sacrifices and resilience of those who came before.

To put that into perspective…Some of our ancestors had never traveled more than 20 kilometers from their homes during their lives to that point. Some had never seen the ocean. In our family’s case, they were all farmers who were used to the Northern Hemisphere agricultural practices & climate conditions, so they would have had no idea what conditions were going to be like in Australia. I wonder, how many knew that Australia was, & still is the driest continent in the world. I’d be willing to bet that the Queensland Government delegations to Germany & the UK back in the 1800s, drumming up prospective immigration, weren’t passing on that information. Our ancestors all made an incredible leap of faith in what was awaiting them on the other side of the world.

Ancestry research is always a work in progress. It’s rarely possible to create a complete account of lives from over a century ago due to limited recorded information. Unlike today, when nearly everything is documented—often down to photographs of last nights dinner and the smallest details of daily life—records from the past are far more fragmented.

While I don’t believe in using assumptions to fill in the gaps, it’s often necessary to help connect the dots. Unless your relative led a very public life, records are limited to shipping logs, birth and death notices, cemetery markers, and sometimes a rare photograph or two.

Studying the conditions in Germany and Ireland from where our ancestors came provides context. Some records I’ve found don’t align perfectly with others; I attribute this to the day’s inconsistent record-keeping. However, sometimes it’s a mistake to dismiss details due to minor discrepancies.

Take my great-great-grandmother Catherine Ryan, for example. She arrived in Brisbane in 1852, to a town that was barely more than a village. The free settler population was small, and Queensland only started recording immigration in 1848, a decade before statehood. With relatively few Catherines of her age group arriving in the early 1850s, tracking her wasn’t impossible, just challenging. By categorizing records and eliminating obvious errors, I’ve narrowed her arrival time to a point shortly before her marriage on November 8, 1853.

In the official Queensland Assisted Immigration records, there were only four female Ryans listed in the 18–25 age group who arrived by 1853, and only one named “Catherine Ryan.” Some assisted migrants, particularly single young women, would adopt a family for the journey. This was common on migrant voyages to the US, Canada, South Africa, and Australia, as having a family on board provided young women with a sense of protection in an environment where security was often non-existent.

In some rare cases, a few traveled under a false name. People back then were not so different from today: some lied about their age or activities for various reasons, and over the years, some records disappeared or were accidentally destroyed. Anyone researching ancestry can attest that not all official records are reliable. Dates, spellings, and shipping records were often haphazardly recorded. When researching my great-great-grandmother Catherine Ryan, it’s been an exercise in connecting dates, places, records, and media reports. I always ask myself, “Does this person’s location and timeline match my ancestor’s?”

However, using Catherine Ryan’s case as an example, she travelled to Australia as an assisted migrant in the years following the initiation of the Irish Workhouse Orphans scheme.

In many ways, I’m grateful that our Catherine Ryan came to Australia from Ireland as a free assisted migrant, even though she was a workhouse orphan. While reviewing lists of Irish female convicts transported to various parts of Australia during the famine period, I found no fewer than seventeen women named Catherine Ryan. This gives you a sense of how challenging it can be to accurately trace an ancestor.

A quick way to start a debate with other ancestry researchers is to hold rigid opinions without rock-solid evidence. Entering genealogy research, you need the humility to accept that you might make mistakes and the respect to acknowledge that others may have it right. No one gets it right the first time. I’ve learned that talking to and listening to as many people as possible is invaluable. Older relatives, in particular, are an incredible source of information. Many are eager to share their stories with someone who will listen. If no one records their memories, significant historical details or family stories may vanish.

There are, of course, many myths and exaggerated stories passed down through generations. Just as today, people a century ago made up tales to discredit someone they disliked. They didn’t have digital social media but relied on word-of-mouth and, later, newspapers. Sorting fact from fiction is crucial for creating an accurate family history.

It’s also essential to understand the business model of genealogy sites like Ancestry.com, MyHeritage, and FindMyPast. They are not benevolent organizations. They trickle information to keep you engaged, encouraging you to maintain memberships. However, their vast records are worth the cost—just don’t rely solely on them. Many free archives and local libraries hold original records. Some of the best resources are small, volunteer-run local archives. I highly recommend visiting these places in the areas your ancestors came from. Many families donate photos and records from estates, so new information arrives regularly. Even a brief mention in another family’s records can reveal new insights into your own family history.

Regional history social media groups are another excellent resource. Descendants of pioneer families still living in these areas often post historical records, old photos, and landmarks from their family collections, especially after an elderly relative has passed away. These groups are also a great way to connect with distant family members.

I continually update my ancestry articles as I uncover more accurate information. With only about 3% of Queensland State Government Archive records online as of 2023, there’s always more to find. It would be helpful if our State Archives took a more proactive approach to digitizing these old records. Compared to other Australian states, Queensland’s online access is disappointing.

Recently, at a family reunion, a distant relative remarked that our family “had no shady dealings” in the past. Since starting this journey, I’ve held the view that whatever happened in the past remains a part of history—good or bad. We shouldn’t hide any nefarious activities; they’re part of our family’s story, and I’d want them included in any records. Luckily, our family doesn’t appear to have any infamous characters. 😃

During that same reunion, a few cousins and I discussed whether we felt a particular affinity with certain branches of the family. Some identified with a family line because of farming heritage, religious connections, or common interests. Personally, I feel connected to all my ancestors. While I don’t share their conservatism or religious values, I’m proud of what they achieved after arriving in this foreign land. Each of them, in their own separate ways brought something to the table, either their individual life skills, the raising of their families or just their moral compass throughout their lives.

GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCES :-

In tracing the trail of past relatives, I’ve found that most families have a few skeletons in the closet. It seems our early Australian ancestors often viewed certain issues as potential sources of disgrace, going to great lengths to ensure these details didn’t reach the outside world. My research suggests that sometime in the early to late 1800s, Victorian-era Australia—and likely other countries—experienced a moral shift toward ultra-conservative views. This change impacted everything from political and religious perspectives to daily life and personal conduct.

In Australia, during this conservative period, most people held strong religious beliefs and a fervent loyalty to King/Queen and country. They viewed the world—and their place in it—through a very different moral and cultural lens. With no internet or television and only newspapers as the primary media, people generally trusted what they read. In rural & regional areas, traditionalists were often resistant to groups that challenged the local social and religious norms. I can imagine how horrified Australians from the mid-1800s to the 1960s would be by today’s moral standards. Conformity was expected, and nonconformity was often punishable. Crimes like cattle & stock stealing, burglary, forgery, treason, and even homosexuality could carry the death penalty. Acceptance of minority groups, including the LGBTQIA+ community, was virtually nonexistent. Being openly gay could lead to brutal violence, often resulting in expulsion from the community. If arrested, there was little hope for leniency or protection from the police, who would sometimes participate in or even initiate violent abuse in custody, inflicting their own form of punishment.

How times have changed! Today, we’ve nearly reversed that conservative stance. However, mainstream TV and print media now often manipulate news to align with editorial standards and political biases. Many people attempt—though not always successfully—to find unbiased news through internet sources. By 2024, fact-checking has sadly become essential for anyone seeking accurate news and current affairs. The Fourth Estate sometimes appears to wield the power to dictate national governance rather than report impartially. There is a fine line between the hard-won ideals of freedom of speech and the press and the current state of sensationalized editorial content. News outlets, such as the Murdoch Media Group in Australia and many other organizations worldwide, operate under the guise of providing news to the public while advancing their own political and editorial agendas.

We also live in a world where oversharing personal lives on social media has become the norm. With the rise of mobile phones equipped with cameras and recording features, privacy and modesty are less of a priority. While our ancestors could trust a photograph as factual evidence, today’s technology has made it difficult to know what’s real. Fake news is everywhere.

AI INFLUENCE – While I have embraced many newer technologies that make ancestry research easier—and have even used AI myself to restore old photographs to clearer, more modern standards—the rampant use of AI to modify images and alter records to fit particular narratives deeply concerns me. In some cases, history is being rewritten to validate certain agendas, with vested interests—sometimes political or even extremist—attempting to distort historical facts to promote their own views.

Some may consider my stance on AI somewhat hypocritical, but I believe there is a vast difference between enhancing an old, damaged sepia-toned photograph and grossly altering an image to serve propaganda purposes. That’s just my opinion—you don’t have to agree with me. I also make it a point to label any photographs I have modified, so others are aware of the improvements I’ve made. From my perspective, it’s important to remain cautious and always check records for authenticity.

EMOTIONS – SHAME & HUMILIATION – Regarding the notion of shame, many of our past relatives felt embarrassment over their convict ancestry from the 1700s and 1800s. Shame is an interesting emotion, as it’s often tied to what others might think of us, rather than a direct reaction to something we’ve experienced ourselves. Practically all the convicts transported to Australia were punished for relatively minor crimes—many simply had the misfortune of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Most were poor and lacked access to legal support, so they were sent to the ends of the earth with little chance to prove their innocence. Many were treated poorly after gaining their freedom, with their employment prospects severely limited. However, many modern descendants now wear their convict heritage as a badge of honor.

The issue of shame was significant in early Australia, which was highly structured. The military governors, soldiers, police, courts, and jails formed the only governing system in place. At the bottom of the social hierarchy were the convicts, transported to Australia as a solution to Britain’s severe prison overcrowding. British prisons were so full that convicts were held in old shipping hulks on the Thames River.

With Australia discovered by Captain James Cook in 1770 and America no longer an option for Britain’s unwanted criminals, transporting convicts to the new colony became a logical solution. By 1788, this strategy served a dual purpose: alleviating Britain’s prison crisis and providing a labor force for Australia.

The shame factor emerged later as Australian society became more structured. The governors, military, legal system, and later the squatters and landed gentry, who arrived seeking wealth, wanted a cheap and compliant workforce. Additionally, Britain saw Australia as a convenient place to send its suppressed Irish population. In the aftermath of the Great Famine of the late 1840s, large numbers of desperate Irish immigrants were shipped to Australia, further meeting the colony’s labor demands.

The landed gentry, who viewed themselves as the aristocracy of the emerging colony, were content to reinforce the stigma surrounding convict origins and Irish ancestry, ensuring a steady supply of low-paid workers. Despite their significant contributions to Australia’s history and development, both ex-convicts and Irish immigrants were often compelled to hide their backgrounds in the early days of free settlement. However, this was not easily done. The strong Irish brogue of the immigrants and the widespread lack of literacy among both ex-convicts and Irish settlers made it difficult to conceal their origins. While this ensured a subordinate labor force for the colony, it also fueled a persistent political debate that echoed the tensions in the United Kingdom.

–

As a personal observation, many modern-day Australians continue to focus on the perceived wrongdoings of the nation’s early leaders. It is undeniable that Australia has been home to a diverse range of nationalities since the early days of settlement. In addition to convicts and the Irish, large numbers of mainland Europeans fled war-torn Europe in the 1800s. Chinese, Greek, and Italian immigrants also arrived well before World War I, all seeking a new life. Even in its early years, Australia was one of the most multicultural countries in the world. While acknowledging the mistakes and injustices of past administrators is important, they should not overshadow the nation’s progress and identity.

FAMILY MYSTERIES

We still have a couple of family mysteries to solve.

One is about my great-grandfather, Peter Bermingham. As mentioned in my blog article about him, I know he arrived in Australia in 1874 at Maryborough and likely died around 1908. He married my great-grandmother, the recently widowed Ellen Dunn, in 1877, and they had a child—my grandfather, Edward Bermingham. They farmed at South Pine. But that’s where the information ends. There are no citizenship records, no voting details, no census data, no death notice, no official date or place of death, no funeral, no grave—nothing. Who was he? Did he leave the country, commit a crime, or end up in jail or an asylum? Was he murdered or did he take his own life? There are so many unanswered questions about Peter Bermingham’s life and disappearance. Most of my other ancestors left clues along their lifelines, but Peter left almost nothing about his life in Australia after his arrival from Ireland. What did he do, and why did he disappear without a trace?

The second mystery is about my great-great-grandmother, Johanna Elizabeth Grambauer. I know she was born in Germany in 1828 and died in Kalbar, Queensland, in 1902. Her husband was Carl Kruger, with whom she had six children. They farmed in the Fassifern Valley, but aside from these few details, she remains a mystery, much like Peter. She appears to have been a stay-at-home wife and mother, yet I believe there’s more to her story. However, despite my efforts, she remains another unresolved piece of our family history.

Closing Comments & Observations on Ancestry Tracking

Ancestry tracking is a truly captivating hobby that attracts a wide variety of people. Some, like me, want the whole story—warts and all. I don’t care if my ancestors were criminals, paupers, or wealthy individuals; I just want the complete, unvarnished truth. Others prefer to bask in the highlights or the “good parts”, selectively including connections to wealthy individuals or celebrities while omitting any embarrassing details, such as criminal records, mental health issues, or adoptions. Then there are those who, despite uncovering a wealth of family information, seem reluctant to share it. They almost guard it as if they alone should preserve their family’s history.

I understand that many people are private individuals who may not have the communication skills to appreciate the importance of this ancestry work, but for goodness’ sake, step over your embarrassment and share what you’ve found. If you don’t, it will all disappear. Our family history is just that—it’s our collective past, and we are merely custodians, responsible for passing it down to future generations.

Even now, I still uncover information that can completely overturn previous research I once believed to be accurate. Sometimes, the true story turns out to be more mundane or less captivating—but it’s still the truth. And that matters.

So yes, there are times when entire sections of an ancestry story must be removed and replaced with historically accurate facts. The key is to prioritize accuracy and eliminate any embellishments or misinformation.

What’s truly surprising is how some family members continue to cling to inaccurate details, unwilling to admit they’re mistaken—even when presented with clear evidence.

It’s disappointing to have to remove entire chapters once you discover they’re wrong, but I see it differently: I want to get it right. That’s all that matters.

When reaching out to relatives and others for information, it’s a fine line to walk. Some people clam up completely, while others are simply too shy to share. But the more people involved, the larger the pool of knowledge, records, and photographs. I became interested in our family’s history when my daughter-in-law asked about it, and I realized I didn’t have many answers. That set me on this quest for facts.

Photographs & historic records. Initially, I didn’t find many records from my immediate family. My parents, for one reason or another, had very little documentation. However, a couple of distant cousins, Mary (on my Dad’s side) and Trevor (on my Mum’s side), had treasure troves of old photos and records passed down to them. Both had already put significant time into researching each side of our family, which saved me a lot of time. Fortunately, they were happy to share everything they had. My sister Jen has also found valuable information, and our extended family has generally been cooperative.

It’s unfortunate when families refuse to share their history, sometimes taking it to the grave. Once lost, it can’t be retrieved. For those uninterested in preserving family records, I urge them to donate these valuable pieces of history to local historical societies or museums—please don’t just throw them away. I’ve heard shocking and tragic stories of relatives discarding or burning old photo albums and records simply because they lacked personal interest. Such actions are shameful. Once these priceless records are gone, they’re lost forever, often due to someone’s careless neglect.

However, there is a downside to donating to museums: photos and records are often unlabeled, so they may lose their identifying details and end up buried in archives. Family records generally hold true meaning only to descendants, for whom they are priceless treasures with immense historical significance.

Discovering a rare photo of an ancestor is one of the most exciting parts of ancestry tracking. The saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” is absolutely true. Even a faded or damaged photograph adds a new dimension to a person’s story. Often, you can see traces of their struggles and experiences in their facial expressions. However, a word of caution—make sure the photograph is correctly attributed. I’ve seen people mistakenly associate photos with the wrong individual, sometimes attaching incorrect images because they didn’t bother to verify.

One day, a family member will ask, “Who are we, and where did we come from?” It’s good to be able to provide a factual answer instead of a fabricated story that some families prefer to spread.

We have a responsibility to record our ancestors’ stories before they fade away. Whether gathered through conversations with elderly relatives, family records, photographs, library archives, or online sources, someone else has likely done the initial legwork. Genealogy research often builds upon copying and pasting from earlier records.

Since beginning this journey, I’ve observed people cherry-pick historical records to fit their own narratives. Some make tenuous connections to well-known figures—like the infamous Australian outlaw, Ned Kelly. Kelly was a murderer, thief, and bank robber, yet he has become something of a folk hero in modern Australia, with a significant cult following. Many compare him to a Robin Hood figure, when in reality he was a cold-blooded killer.

It’s essential to ensure your findings are accurate and to correct any mistakes. Some ancestry researchers become defensive when their conclusions are questioned. Online discussions can often turn heated, with individuals clinging firmly to inaccuracies. In contrast, in-person conversations tend to be more productive.

I’ve had coffee and shared meals with many genealogy enthusiasts, and most are eager to both share their knowledge and learn from others. Early on in my journey, I realized the importance of keeping an open mind when analyzing ancestry records—whether they’re official documents or family stories passed down through generations.

Some people have a tendency to stubbornly hold onto incorrect information, even when presented with verified facts. It’s not about belittling anyone; as someone who values accuracy, I simply strive to get the story right. Occasionally, you’ll encounter individuals who are more interested in having the last word than in uncovering the truth.

That’s why it’s vital to check, check, and recheck your research. Be prepared to let go of long-held beliefs if new, credible evidence comes to light. It’s not about saving face—it’s about honoring your ancestors by telling their true story.

One of the most valuable tools for ancestry tracking has been DNA testing. Though it has existed for about 40 years, DNA testing has only recently become widely accessible, providing a more precise way to link ancestors to descendants. It confirms family relationships, assuming that some family members also participate. Of course, DNA testing can open a Pandora’s box. You might discover unexpected connections, like non-biological parents or a criminal relative. On the other hand, you could find out you’re related to someone famous. DNA tests have also reopened cold cases, as genetic links have allowed police to identify suspects through relatives. If you decide to take a DNA test, be aware that it could have far-reaching implications. We all like to think we have no secrets, but a simple ancestry test can reveal much more than you anticipated.

I was fortunate to have relatives who had already done extensive research before I got involved. This journey has also reconnected me with people I hadn’t seen in years and introduced me to family I had never met. I know many people start this process and soon give up. My family history was easier to trace since nearly all our ancestors came from just two countries—Ireland and Germany. They arrived in Brisbane and settled in the Fassifern Valley. Starting from scratch with multiple ethnic backgrounds would be far more challenging. My DNA is roughly 50/50 Irish and German, but I’m now exploring my granddaughter’s Indian ancestry on her mother’s side so that she may have her own paths to follow someday.

I’ve also encountered people who rely on century-old newspaper articles as factual evidence. With all due respect, historical newspapers were not always accurate. Back then, as now, sensationalized human-interest stories were common, sometimes prioritizing circulation over facts. Just because it’s in print doesn’t make it gospel truth.

In Australia, we have Trove which is a free, online resource maintained by the National Library of Australia that connects users to digital collections from hundreds of Australian libraries, museums, galleries, media outlets, government, and community organizations, offering access to a vast trove of cultural material and stories. It includes digitized newspapers, books, journals, images, maps, websites, and more. It is possible to access multiple different sources to verify media facts of the day. Unfortunately, there are still some copyright issues with Trove, not allowing them access to some newspapers, surprise, surprise, that are affiliated with outlets like the Murdoch press, but in saying this, it is a valuable tool in tracking down old articles about relatives & times from Australia’s past.

I believe ancestry research should be available to all who are interested. I welcome critiques and fact-based responses, and I’m not concerned with people copying my records—they’re historical facts, not my personal property. I’d rather see the whole story shared as widely as possible.

Our family history includes farmers, laborers, teachers, medical professionals, and servicemen who fought and died in wars. They worked hard to make a living, often under difficult conditions. Many lost children in infancy, and our family members have served as soldiers, Anzacs, and in numerous professions. These lives, though not sensational, are a testament to resilience and tenacity.

One of the great things about ancestry research is the opportunity to reconnect with long-lost relatives or meet family members for the first time. A distant cousin I recently met asked about my knowledge of farming practices. I explained that although nearly all my ancestors were farmers in the Fassifern Valley—growing various crops, raising dairy and beef cattle, sheep, and pigs, and breeding stud cattle and Clydesdale horses—my siblings and I were born and raised in Brisbane. As a result, we grew up as city kids, and my knowledge of farming could fit on the back of a postage stamp.

Despite your efforts, sometimes you hit a brick wall in your research. I encourage anyone who faces this to keep going. Ancestry tracking is a marathon with no finish line. Fresh discoveries are constantly emerging, often revealing things you may have missed the first time. I regularly find new information about our ancestors, which I then add to the story. You can track back to distant ancestors only to come to a dead end or suddenly find that your research may be faulty. The whole exercise can do your head in sometimes. It’s a hobby that you can park at any time & later pick up from where you left off. It’s definitely an exercise in perseverance.

My sister, along with a few others, has suggested more than once that I put all of my records into book form. I have resisted this for several reasons. One of them is that, as I am the first to admit, I have made mistakes in recording my family history and research for my family tree and blog articles.

The beauty of writing a blog about each ancestor is that it remains fluid. You can revise it as you discover errors or uncover new information to add to their individual stories.

One surprising discovery I made during this ancestry-tracking journey was an awareness of my own reflections on the process. Following various historical groups on social media, I noticed that some people develop an almost obsessive, overly enthusiastic admiration for their ancestors. Over time, I’ve come to believe that our ancestors were just ordinary people, much like us, simply living and working in the times they were born into. From a modern-day perspective, some view them as people who achieved miracles, but in reality, they were shaped by the limitations of their conditions and the moral and environmental understanding of their era. They were products of their time and place. Some we may feel an affinity for, while others may have been difficult or even unpleasant, yet we must accept them for who they were—our ancestors. We may disagree with their politics, beliefs, or morals, but they are who they are.

A crucial detail that many family genealogists sometimes overlook is how easy it is to get caught up in the excitement of uncovering facts and details about ancestors we could never have known personally, given that they lived over a hundred years before us. In this enthusiasm, we may inadvertently draw conclusions that never actually happened. It’s an easy mistake to make.

As a researcher, you might come across a trove of information and start forming opinions about your ancestors’ lifestyles and attitudes. This often happens in the excitement of discovery—I’ve seen it in many researchers’ stories, and I’ve been guilty of it myself. It’s important to develop the ability to stay objective and grounded in facts. I make a habit of going back through my records and files to recheck information.

Many people tend to get carried away with the more heroic aspects of their ancestors’ lives. They often focus on the adventurous parts of their stories while overlooking less dramatic but equally life-changing events. Staying true to the complete picture of an ancestor’s life is essential for an accurate and meaningful genealogical record.

Your ancestor may not have been a renowned figure like Captain James Cook—one of history’s most accomplished navigators and explorers, celebrated for charting Australia—but perhaps he was a crew member aboard Cook’s ship. Though he wasn’t famous, he still played a vital role as part of the crew on the Endeavour. It’s important to focus on the facts.

All of our ancestors traveled vast distances from across the world to reach Australia. However, once they arrived, most of the original settlers remained close to their homes and towns.

Over time, many of their descendants ventured farther afield. Initially, their career paths took them to various parts of Queensland, and in more modern times, career opportunities and marriages led our family members to settle in different parts of Australia & the world.

Below is a list of locations where our ancestors and their descendants lived, raised families, and eventually settled. These places span Queensland and other parts of Australia:

Queensland Locations:

Amberley, Beaudesert, Biggenden, Boonah, Brisbane, Buderim, Caloundra, Childers, Croftby, Dalby, Fassifern Valley, Gatton, Grandchester, Hughenden, Ipswich, Kalbar, Kelvin Grove, Laidley, Lutwyche, Mackay, Manly, Maryborough, Moogerah, Munruben, Nerang, New Farm, Nudgee, Oakey, Obum Obum, Purga, Roadvale, Rocklea, South Pine, Sunshine Coast, Telemon, Toowoomba, Townsville, Walloon, Warwick, Wynnum.

Other Australian Locations:

Grafton NSW, Koreelah NSW, Launceston TAS, Maitland NSW, Melbourne VIC, Newcastle NSW, Parramatta NSW, Perth WA, Point Cook VIC, Sydney NSW.

No doubt, I have missed some, so please bring it to my attention & I will rectify.

In closing, I began this journey seeking to understand who my ancestors were and to gain insight into their lives. I’ve come to the conclusion that they were all achievers in their own ways, some reaching higher than others.

The story is about them - My ancestors!

IF YOU COULD SEE YOUR ANCESTORS, ALL STANDING IN A ROW,

WOULD YOU BE PROUD OF THEM OR NOT, OR DON’T YOU REALLY KNOW?

SOME STRANGE DISCOVERIES ARE MADE, IN CLIMBING FAMILY TREES,

AND SOME OF THEM, YOU KNOW, DO NOT PARTICULARLY PLEASE.

IF YOU COULD SEE YOUR ANCESTORS, ALL STANDING IN A ROW,

THERE MIGHT BE SOME OF THEM PERHAPS, YOU WOULDN’T CARE TO KNOW.

BUT HERE’S ANOTHER QUESTION, WHICH REQUIRES A DIFFERENT VIEW –

IF YOU COULD MEET YOUR ANCESTORS, WOULD THEY BE PROUD OF YOU?