Reading time 65 minutes

I love a good story—one with a compelling plot, a hero, villains, diverse settings, dramatic content, and a well-structured beginning, middle, and end. When the story is factual and evokes emotional resonance, it becomes even more powerful.

This is the true story of Catherine Ryan, my great-great-grandmother. Like many great tales, it started as a simple quest to answer basic questions: Where was she from? Why and how did she come to Australia? What kind of life did she have in her new country?

As I delved deeper into Catherine’s life, I had no idea what I would uncover. There were many shocks and surprises.

Anyone who commences to research an ancestor’s history soon realizes that you’re trying to unearth details about someone who has been dead for over a century. How accurate will any of it be?

I think that at some point during this journey of discovery, most of us reach a moment where we think, “OK, stop now. Go with what you’ve got.”

But in Catherine’s case, I found there was much more to her than just the basic dates and places. She was a woman of real substance. And like many of our recent ancestors, she lived through a period of great technological, industrial and social change.

My intent was to uncover the hidden aspects of her life that are difficult to unearth: What was the generational mindset of the Irish in their homeland, and later, when they arrived in Australia? What attitudes did colonial Australians have on politics, religion, and education? How did she—and her contemporaries—react to issues like sexism, racism, the environment, and crime and punishment? Did she have a hobbie or pastime?

In researching Catherine’s life, I wanted to portray her as more than just a two-dimensional character, which often happens when writing about ancestors. While it’s important to stick to the facts, there are instances where I’ve connected a few dots. I’m not advocating for propping up a story with inaccurate guesswork, but by analyzing the subject’s living conditions, their status in the community and the economic state of their town and country at a given time, it is plausible to link the person to that time and place with a high degree of accuracy.

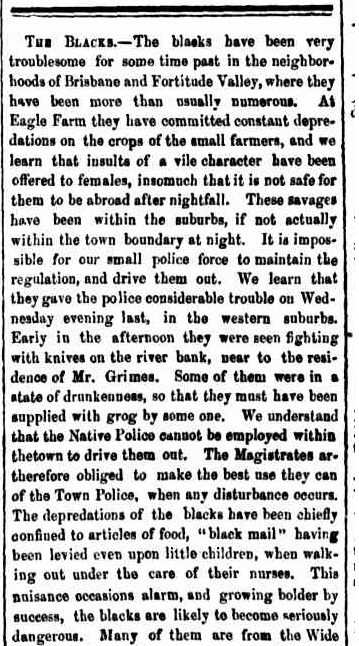

Much of this information is now more accessible thanks to old newspapers from Ireland and colonial Australia. Reading the actual print media of the mid-19th century, which detailed the stories of the day, provides incredible insight into the attitudes of the general population during that time. The wording and tone of news articles, advertisements, and letters to the editor give us a fairly accurate idea of the thinking of that period.

Before you dismiss this theory, consider it in comparison to modern-day social media. Both outlets provide a reasonable reflection of the attitudes of a cross-section of their respective communities. Some opinions, often with political overtones, are extreme. Some come across as aggressive and negative, while others are calm, logical, and sensible. Somewhere in the middle lies the consensus, where you typically find the majority.

So, although this is primarily Catherine’s story, it is also a story about the era she was born into and the timeline throughout her life.

It is a saga of survival and dogged determination.

The first thing I realized was that, like many of our ancestors, she was a product of her time. The events and experiences she encountered in her first two decades shaped the rest of her life. Although Catherine came to Australia as an assisted migrant, her early years in Ireland share many similarities with the treatment of convicts sent to Australia during the colonial period. Unlike the convicts, she may have been considered free, but the harsh reality of life in Ireland during Catherine’s formative years was that it had been turned into a virtual prison by the ruling British government.

Catherine Ryan was our family’s earliest female ancestor to arrive in Australia, in 1852. Her future husband, Robert Bradbury, was our earliest male ancestor to arrive, in 1832. To learn more about my great-great-grandfather Robert Bradbury, the link to his story is here https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/11/08/robert-bradbury-2/

DEFINING PERIODS IN IRISH HISTORY LEADING UP TO CATHERINE RYAN’S BIRTH

Ireland had reluctantly been officially part of the United Kingdom since 1801, although English control had been in place since the Norman invasion in 1169. This conquest marked the beginning of over 800 years of English political and military involvement in Ireland. In the early 1800s, the British government ordered the Royal Irish Constabulary to suppress the unrest, the root cause of which was the government’s relentless harassment and persecution of the predominantly Catholic population.

When Catherine Ryan was born, the county of Tipperary had a larger-than-average Catholic population, leading to heightened tensions between the minority Protestant establishment and prominent Catholic families. The region was a significant grazing area with a simple social structure: one was either a Protestant landowner or a Catholic herdsman at the bottom of the social hierarchy. There were few intermediate categories of tenants. This part of Ireland witnessed the sharpest and most direct conflicts between these factions. From the early 1800s onward, and especially as the famine began, open gang warfare occurred between Catholic and Protestant groups in Tipperary. The Catholic agrarian movement in County Tipperary operated under various names during this period, but their principles remained consistent: they sought a united Ireland, free from British aggression, with the right to self-determination.

To fully understand these events, it is necessary to look further back in time.

The British government had waged an ongoing campaign of ethnic cleansing in Ireland for centuries, with the tacit support of successive British royal families and the Protestant ruling classes in England. Despite coercion and force by the ruling Protestant UK government in London, the religious majority of the Irish nation remained steadfastly Roman Catholic. Historically, Britain has fostered religious divisions and bigotry among the Irish people to maintain control by dividing them.

In 1695, the British government introduced repressive laws intended to persecute Catholics. The Irish Penal Laws of 1695 intensified the injustice inflicted by the Protestant English, stripping Catholics of religious freedoms and nearly all of their holdings, including land. Under British rule in previous centuries, the Irish were treated as non-persons, stripped of legal personhood. Since murder requires identity, the Irish were legally killable by any English person at will.

Catholics were forbidden to keep birth, marriage, and death records, obtain an education, hold a commission in the army, enter a profession, run a business, or own a horse worth more than five pounds. They were also barred from owning weaponry, studying law or medicine, speaking or reading Gaelic, or playing Irish music. While the enforcement of the Penal Laws resulted in widespread poverty across Ireland and consequently led to emigration, it also fostered a sense of unity among those who remained and introduced the concept of nationalism. Catholic priests were banished, Catholic schools were banned, and Catholics were forced to pay a tax to support the Anglican Church. The most impactful laws for the Irish were those surrounding land ownership. The Property Act of 1703, passed by the British Parliament, forbade Catholics from passing down their land.

Catholics finally reinstated the keeping of records in the mid-1800s. There was a gap of about 150 years during which very few official records were kept, aside from individual parish churches recording basic details.

Enforcement – Ok, so how did the British authorities impose these laws?

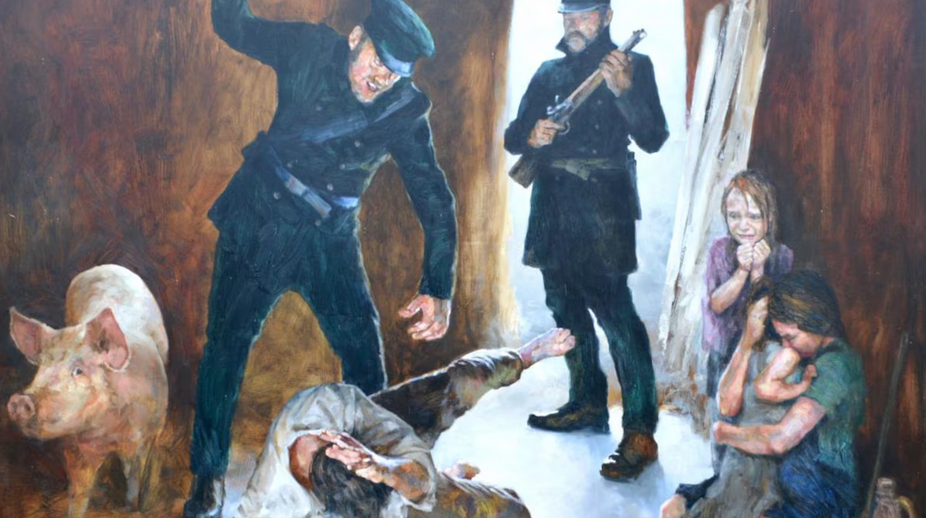

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) operated under the authority of the British administration in Ireland as a quasi-military police force. Unlike police in other parts of the United Kingdom, RIC constables were routinely armed (often with carbines), billeted in barracks, and organized with a militaristic structure. The RIC was responsible for policing Ireland during periods of agrarian unrest and nationalist freedom fighting, often quelling civil disturbances.

For most of its history, the ethnic and religious composition of the RIC generally reflected that of the Irish population, although Anglo-Irish Protestants were disproportionately represented among its senior officers. This Anglo-Protestant dominance led many Catholic rank-and-file members to leave the RIC and pursue police careers abroad. The sectarian and nationalist violence, land clearances, evictions, and protection of landowners during these years fell under the RIC’s responsibility. Many RIC officers resented these duties and subsequently left the service. For example, numerous former RIC members who emigrated from Ireland later joined the Queensland Police Service in the late 1800s, where they became notably overrepresented.

Education

Education standards across Ireland in the 1800s were practically non-existent, with most young people unable to read or write. Although learning standards across the UK were only marginally better, they were beginning to improve. In contrast, Ireland was largely neglected and received little to no assistance from the British government to organize improved schooling for its children.

CATHERINE’S LIFE IN IRELAND C1834 – 1852

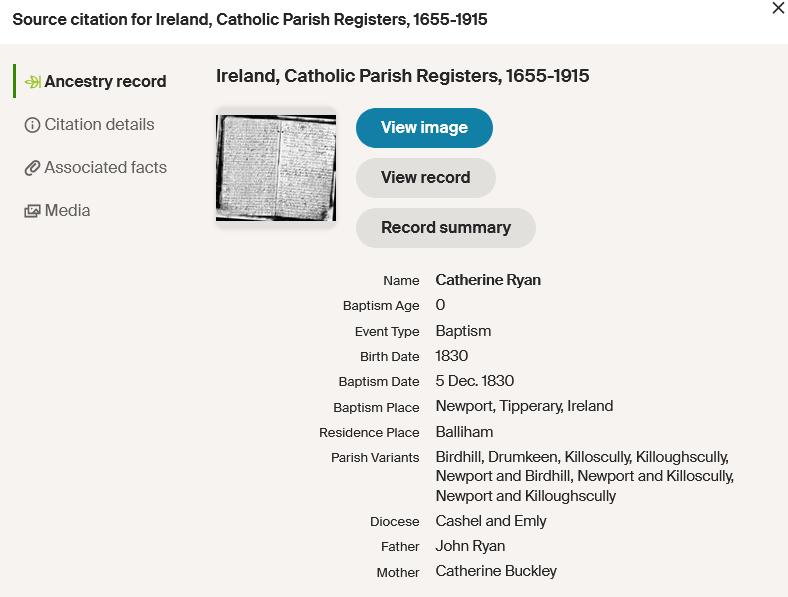

Catherine Ryan was born into a turbulent period in Ireland, likely in the early 1830s in County Tipperary. Although the exact location is unknown, it was probably near Cashel. Her name, Catherine Ryan, was among the most common for girls in Ireland at the time, making it extremely difficult to trace her origins—like searching for a needle in a haystack. In fact, hundreds of baby girls named Catherine Ryan, with parents named John Ryan and Johanna Buckley (or variations of these names), were born across Tipperary during the early 1830s. To my knowledge, Catherine was an only child, and pinpointing her exact date and place of birth may be virtually impossible, as will soon become apparent. Based on details recorded at the time of her death, she was born sometime between 1830 and 1835. Several family ancestry researchers suggest 1830 as her birth year, but I have not been able to verify this conclusively. I am leaning more toward 1833 to 1835. Population of Ireland in 1834 – 7.95 million.

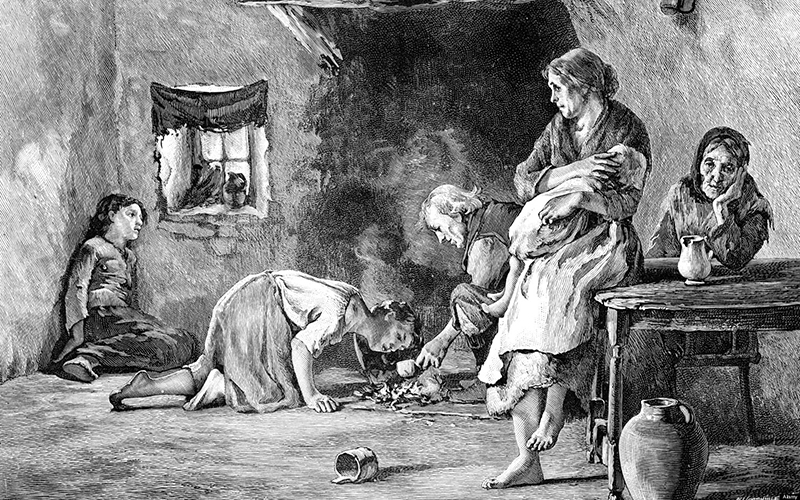

As if tracing her origins weren’t difficult enough, Catherine came of age during one of the most devastating periods in Irish history. Between 1845 and 1852, the country endured An Gorta Mór, the Great Famine—a catastrophic era of mass starvation and disease, ranking among the deadliest famines in world history.

The disaster began in 1845 when the potato crop, the cornerstone of the Irish diet, failed repeatedly year after year. Hunger and disease swept relentlessly across the land. The surge in people seeking aid quickly overwhelmed the system, and the workhouses were pushed far beyond their limits. The population of Ireland in 1847 was 8.5 million. However, by 1850, the population level had dropped to 6.5 million.

By 1850 Ireland was essentially, entirely owned by English landlords, many of them Lords temporal or spiritual, in estates typically of tens of thousands of acres. Their land titles were conquest-based. On these estates the Irish were tenants-at-will on holdings of typically three to eight acres the rent of which they paid by, typically, 250-260 days of unpaid work annually on the landlord’s estate.

In 1843, the British Government recognized that the land management system in Ireland was the foundational cause of disaffection in the country. The Prime Minister established a Royal Commission, chaired by the Earl of Devon (Devon Commission) to enquire into the laws regarding the occupation of land. Irish politician Daniel O’Connell described this commission as “perfectly one-sided”, being composed of landlords with no tenant representation.

In February 1845, Devon reported:

It would be impossible adequately to describe the privations which they [the Irish labourer and his family] habitually and silently endure … in many districts their only food is the potato, their only beverage water … their cabins are seldom a protection against the weather … a bed or a blanket is a rare luxury … and nearly in all their pig and a manure heap constitute their only property.

The period of the Great Famine was indeed a time of profound suffering and hardship for the Irish people, exacerbated by a series of decisions—or lack thereof—by the British government. The Devon Commission’s conclusions about the patient endurance of the laboring classes underscore the deep-seated injustices they faced. The scathing descriptions of landlords as “land sharks” and “bloodsuckers” reflect the widespread resentment towards those who profited from the exploitation and misery of their tenants.

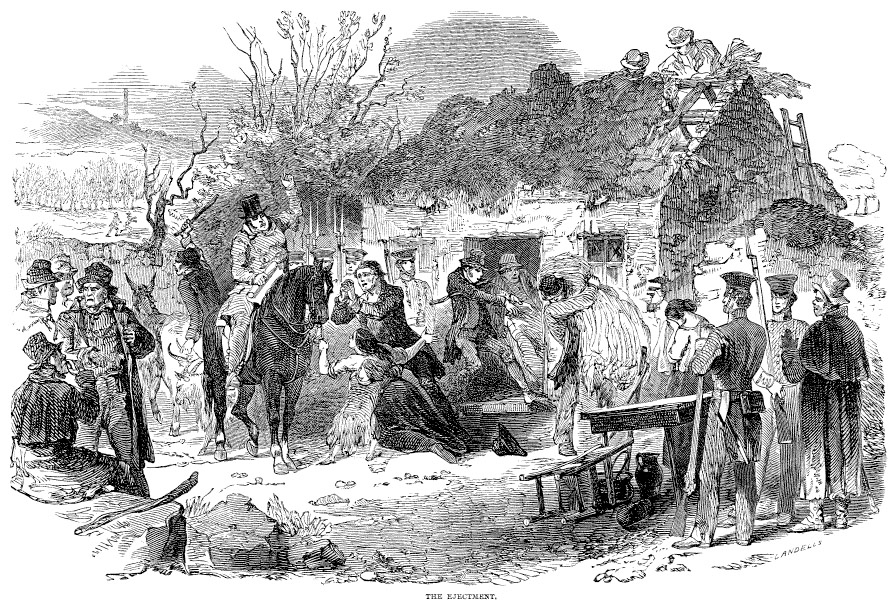

The failure of the British government to prevent the export of food from Ireland, despite the starvation of millions, further fueled the growing anti-British sentiment. This was a time when many Irish people felt utterly abandoned by those in power, who seemed indifferent to their suffering. The mass evictions, often carried out with brutal force, compounded the misery of the Famine, as entire families were left homeless and destitute.

Given this context, it’s easy to understand how Catherine Ryan and her community in Tipperary would have been deeply affected by these events. Even if Catherine was not directly involved in the militant movements around Ballingary, the atmosphere of resistance and the constant harassment by the British-led Irish Constabulary would have been a significant influence on her worldview. The suspicion that the British government was not only neglectful but perhaps complicit in the direction the Famine took adds a dark layer to the historical narrative, suggesting that the suffering of the Irish may have been seen as a means to an end by those in power.

The aftermath of the famine left an indelible mark on Ireland, with the death of a million people and the mass emigration of another million, including Catherine Ryan. The struggle to survive amidst such overwhelming devastation would have shaped Catherine’s experiences and decisions profoundly. Her journey, like that of so many others, was likely driven by a desperate need to escape the horrors of famine and find a place where she could rebuild her life.

The Workhouses

The loss of records and the immense scale of the tragedy during the famine make it challenging to trace individual histories like that of Catherine Ryan‘s parents. Many of the dead were buried in mass graves & went unrecorded. Complete family’s who succumbed to starvation & disease were among those lost without trace. The overcrowding and harsh conditions of the workhouses, where many sought refuge, further complicate the search. The fact that there were multiple teenage girls named Catherine Ryan in the Cashel workhouse registers reflects the widespread suffering and displacement of that time.

Catherine’s story, with its roots in the famine’s devastation, represents the experiences of many Irish families who faced unimaginable hardship during that period. The loss of her parents, her time in a workhouse, and her eventual emigration to Australia encapsulate the broader narrative of survival, displacement, and resilience that defined the Irish experience during and after the famine.

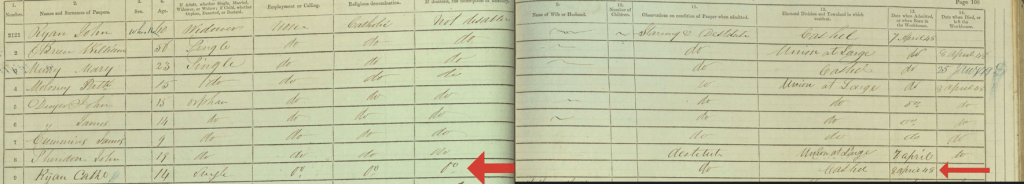

In the above case arrowed of a young girl named Catherine Ryan, it reads as follows……. Name- Cath Ryan,……….age- 14, single,……….employment- none, religion- Roman Catholic,……not disabled,……….no husband or parents,…………observation on condition of pauper when admitted-destitute,……..townland resident-Cashel,…….date of admission-8th April 1848.

Is this record truly for our Catherine Ryan? I cannot say with certainty. It certainly fits her timeline. What I can say is that the workhouse registers provide a sobering window into the heartbreaking realities faced by those who ended up there, particularly during the famine.

Reading the entry for a young girl named Catherine Ryan—with its stark details of her situation: no parents, no employment, and described simply as “destitute”—stirs a deep sense of empathy and sorrow. These brief notations reduce entire lives to a few lines, yet they speak volumes about suffering, endurance, and the resilience of countless individuals.

The emotions that arise from reading these entries are understandable, as they represent real lives, real hardships, and often, the final chapter for many who had nowhere else to turn. The workhouse was often the last resort, and the cold, factual nature of these records can be jarring when contrasted with the immense human tragedy they represent.

This glimpse into Catherine Ryan’s life at the time adds depth to her story, making her more than just a name on a page. It transforms her into a symbol of survival, a young girl who, despite being marked by destitution and loss, managed to endure. Her experience, as recorded in those few lines, is a poignant reminder of the countless untold stories of the famine and of those who survived it.

The higher survival rate of girls compared to boys in workhouses highlights another tragic dimension of famine. Physiological differences enabled girls to withstand extreme conditions more effectively than boys, leading to greater female survival. This resilience in the face of deprivation underscores the harsh realities of human survival during periods of severe scarcity. Historical evidence consistently shows that, on average, women have demonstrated higher survival rates than men during famines, epidemics, and other extreme hardships.

This detail illustrates not only the personal hardship she faced but also the broader biological and social factors that influenced who survived and who did not during the famine. It’s a powerful reminder of the resilience of those who lived through such times, particularly the young girls who, like Catherine, managed to survive against overwhelming odds.

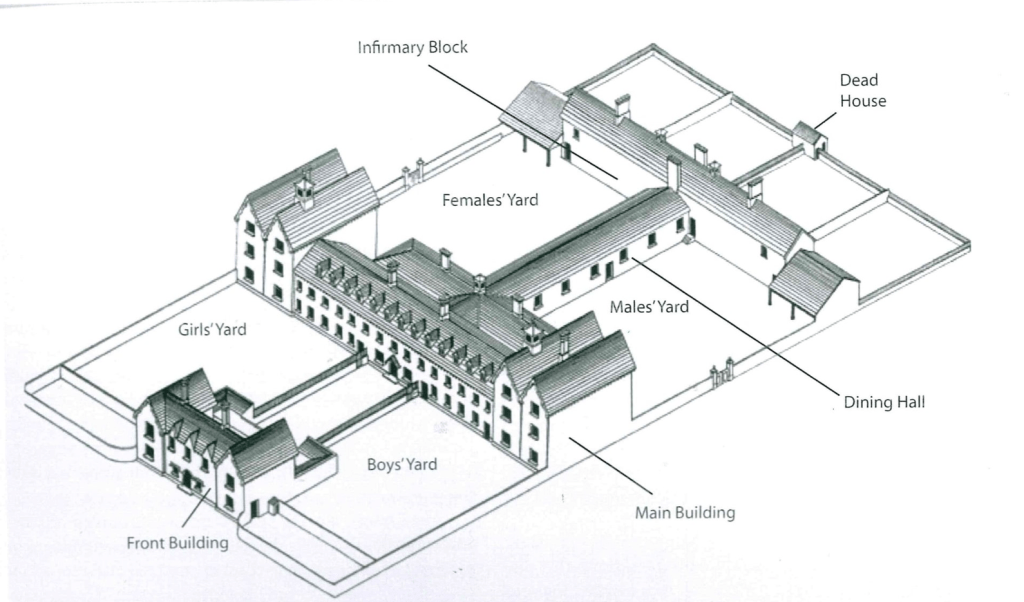

The Cashel Workhouse buildings are still intact. To the rear were kitchens & wash-houses then a single story connecting spine containing a dining hall & chapel. To the rear was an infirmary & “idiots wards”. Most of the original workhouse buildings survive in the shape of the present day St Patricks geriatric hospital.

The workhouses built throughout Ireland during the famine were indeed grim and oppressive institutions. Designed with the barest of necessities, these buildings reflected the harsh policies of the time, where the goal was to provide minimal aid while deterring reliance on public assistance. The decision to exclude decorations and enhancements, and to construct the buildings with a rigid economy in mind, further emphasizes the lack of compassion in their design. With the terrible living conditions, hopelessly inadequate food, lack of sanitation & overcrowding problems within the Famine Workhouses, a reasonable comparison could be made with that of the Concentration Camps of World War Two in Nazi Germany.

The workhouses, already grim and oppressive, became even more harrowing during the famine years as mortality rates soared. With approximately 250,000 people dying within these institutions, they were aptly termed “death houses.” The fear and despair experienced by children who lost their parents, leaving them to face these brutal conditions alone, is heart-wrenching. Many of these children, already weakened by starvation and disease, did not survive, adding to the immense human toll of the famine.

The plight of the Irish Catholic population during the famine, especially the young women like Catherine Ryan, underscores the harsh realities they faced under British rule. With no means of survival, many were forced into workhouses, which became symbols of the oppressive system that broke up families and severed long-standing connections to the land.

The British government’s willingness to exploit the Irish as cheap labor, while showing indifference to their suffering, adds a layer of historical injustice that continues to resonate with people of Irish descent. The conditions in the workhouses, where inmates were subjected to grueling and often meaningless labor, further exemplify the cruelty of the system. For young women, tasks like picking oakum were not just laborious but also punitive, reflecting the broader societal attitudes towards the poor and vulnerable.

This harsh treatment, coupled with the devastating impact of the famine, paints a grim picture of the challenges faced by the Irish during this period. It also highlights the resilience of those who, like Catherine, managed to survive these trials, often carrying the scars of their experiences for the rest of their lives.

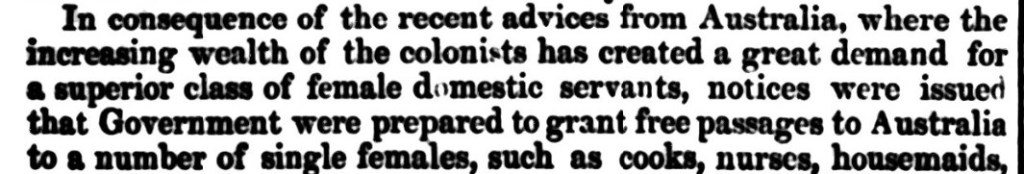

Between 1848 & 1853, more than 4500 young Irish women were resettled as assisted migrants in the Australian colonies. For many of the young girls across Ireland, they were prime candidates to be shipped to Australia, as domestic help and wives for a population that had a large male majority. The selection process was simple. The girls had to be “hearty, humble & fertile women” & were to be young, single, obedient, healthy and free of smallpox. But without supportive networks or family, the girls remained vulnerable and powerless to control their fate.

The first orphan migrant scheme was devised by Earl, Henry George Grey, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to relieve overcrowding in the workhouses and to meet the demand for domestic labourers and single young women in the colonies. Some of the orphan girls died very young; some had extremely harsh lives and others flourished in their new country. The vast majority of them would never see the shores of Ireland again.

Australia had already started to escalate its intake of migrants by the mid 1840s. As a developing country, the population didn’t want any more convicts sent here. Australian farmers needed laborers to clear the land, plant crops, and take care of animals. More infrastructure was being planned to fill the needs of the growing population & a workforce was needed to build it. Although in its infancy, industry in Australia was also starting to generate a need for a much larger pool of skilled workers & tradesmen. While more convicts were gaining their freedom & joining the workforce, those numbers weren’t enough. Each of the colonies within the country was crying out for workers. With Irelands woes, the migration of poor Irish Catholics wanting to escape, was running at a high level.

Sidenote – As a personal observation, I have come to a conclusion that, in later life Catherine would have purposefully decided to put the horrors of her past aside, & distanced herself from what she had endured in her formative years in Ireland. The Irish Catholics, over centuries of persecution, have remained remarkably resilient, & for the vast majority, have adopted an attitude of getting on with life. None will ever forget what they have had to contend with, over the long history of brutal rule under the British. But, the overiding fact is that the Irish are survivers.

CATHERINE’S MOVE TO AUSTRALIA – 1852

By 1851, seventeen year old Catherine Ryan, like many of her peers, was faced with limited choices. Emigration was more of an imposed solution than a voluntary decision. The administrators of the workhouses, in collaboration with the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission in London, organized the mass departure of impoverished Irish female orphans and laborers to destinations like the United States, Canada, and Australia. This was part of a broader strategy to alleviate the overcrowding in workhouses while also fulfilling the labor needs of British colonies.

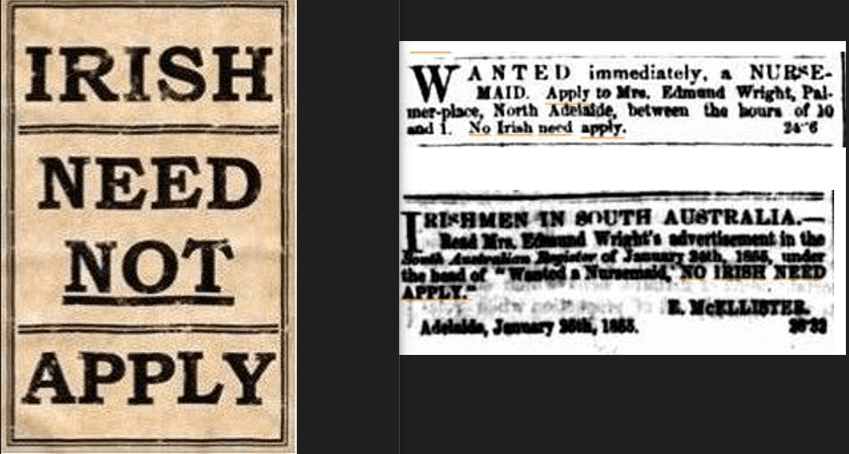

For many young Irish women, including Catherine, the idea of going to England offered little hope. The industrial changes in England had already led to deteriorating living conditions for both rural and urban workers. Additionally, Irish Catholic women faced significant discrimination, physical abuse, and religious persecution in Protestant England. Moving across the Irish Sea often resulted in continuing poverty and hardship. The options, therefore, were stark: emigration, starvation, or enduring the oppressive conditions of the workhouses. In truth, there was no real choice; these young women went where they were directed.

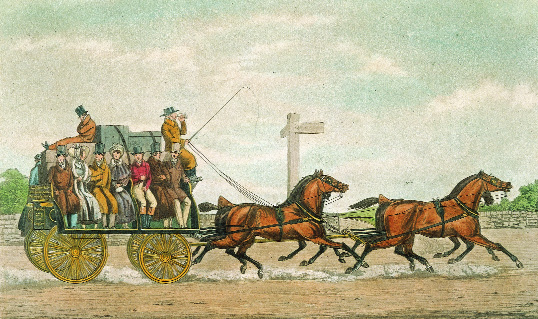

Despite the dire circumstances, it seems that some of the girls had some awareness of what awaited them in Australia, perhaps through word-of-mouth or other sources outside the workhouse. However, the journey itself was grueling. The young emigrants were taken from the workhouses to the Dublin wharf, where they would board a steamer bound for Plymouth Harbour in England, the port of departure for Australia. The conditions of their transport were far from comfortable—26 girls and young men crammed into a horse-drawn carriage designed for 16, highlighting the discomfort and indignity they endured even before embarking on their long voyage to an uncertain future.

The development of Moreton Bay after it had become a free settlement in 1842 was much retarded in its early years by the lack of suitable labour. Manual workers, shepherds, tradesmen, and domestics were sorely needed by the pastoralists and by those living within the town boundaries. This demand led to the sending out of the first immigrant ship under Government auspices towards the end of 1848.

Before 1850, Moreton Bay in New South Wales (now Queensland) was identified as a region with significant potential for agricultural and economic development, prompting interest in increasing its population through migration. Captain John Wickham, the Police Magistrate at Moreton Bay, recognized the region’s capacity to support an influx of migrants, estimating that three shiploads of immigrants per year would meet the area’s labor demands.

However, by early 1852, local landowners & pastoralists, George Leslie and Louis Hope, saw the need for even greater numbers of settlers to drive the region’s growth. They traveled to London to lobby the British Land and Emigration Commissioners, urging them to increase the frequency of emigrant ships to Moreton Bay to one per month. Their efforts were successful, and the Colonial Land and Emigration Office was directed to expedite the dispatch of settlers and assisted migrants to the area.

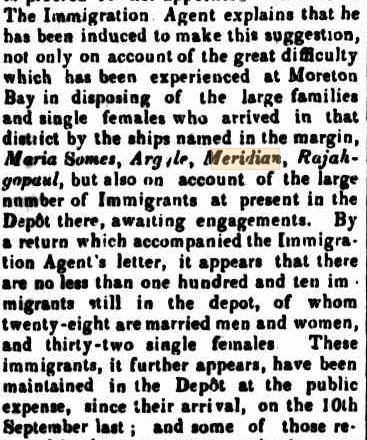

In response, a series of ships were sent to Moreton Bay within a short period. The Maria Soames, Argyle, Meridian, and Rajahgopaul were all dispatched between March 5 and May 5, 1852, marking a significant escalation in the migration efforts to this burgeoning region. This influx of migrants was crucial in meeting the labor needs of the district, particularly in agriculture, and played a key role in the development of Moreton Bay as a thriving settlement.

The Maria Soames was the first of four ships to arrive in Brisbane in 1852. Many of the new immigrants aboard demanded unusually high wages, believing that, as the first newcomers, they were well positioned to take advantage of the colony’s labour shortage. However, their demands for above-average pay did little to help those who arrived later. By the time the other three immigrant ships arrived, wage levels had already begun to fall. This shift was driven by angry squatters who sought cheaper labour and resented being held to ransom by the newcomers’ wage demands.

But, in Australia at the same time, there were many people who campaigned against bringing more poor Irish labourers, into the country. One of them was the outspoken Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang. His fear was that the colony would be swamped by such persons and that Protestant and British liberties would be lost. He also strongly opposed Caroline Chisolm’s campaign to sponsor the immigration of single Irish Catholic women to Australia. But, by the late 1840s, even the Revd Lang realized that he had to soften his views & be a little bit more pragmatic, particularly if the aim was to get single women to travel to Australia in numbers, to fill the many domestic jobs that were vacant in the expanding colony of New South Wales & into the area around Moreton Bay, where the transportation of convicts had now ceased.

The Rev Lang wasn’t alone in his criticism of the Irish immigration schemes. There were many others in Australia who weren’t enamoured with the idea of bringing poor Irish girls to the colony. Upon arrival in Australia, the girls often found that their Irish working-class moralities and values clashed with the English, Victorian middle-class society of the time. Antipathy towards the orphans centred on their youth, incompetence, lowly workhouse origins and, most of all, their Irishness.

Some of the media comments across Australia, that were recorded from newspapers of the day-

……….. barefooted little country beggars, swept from the streets into the workhouse, and thence to New South Wales……..

…….notoriously bad in every sense of the word, thirty-four (34) of them were sent straight to Moreton Bay………

…….Many of these orphan flibbertigibbets are marrying former convicts which is hardly surprising given the history of the Moreton Bay settlement.………. Side note – Our very own orphan flibbertigibbet – Catherine Ryan, married a ticket of leave convict, Robert Bradbury.

…….Irish female immigrants were most unsuitable to the requirements of the Colony, and at the same time distasteful to the majority of the people

……..Their disinclination to learn, their dirty and idle habits, low-class, licentious and unruly

…….In some, ‘a morose and ungovernable temper’

………..Irish orphans were ‘useless trollops’ who did little for ‘their’ colony.

…….Even worse, as future mothers, the girls threaten to imperil the supposedly vigorous colonial physique, with ‘their squat, stunted figures, thick waists and clumsy ankles’.

…….Another shipload of female immigrants from Ireland has reached our shores & yet though everybody is crying out against the monstrous infliction, and the palpable waste of the immigration fund, furnished by the colonists in bringing out these worthless characters …”.

………perhaps prejudging the young women is harsh but it had led to the condemnation of them all, not just a few, as prostitutes, ill-disciplined and promiscuous during the voyage, and ill-suited for work in the colonies.

………..for the reception of the female orphans landed upon our shores, where the most disgusting scenes are nightly enacted. I will not try to portray the Bacchanalian orgies to be witnessed there every night…

……….We venture to say, every vessel that brings an increase of this kind to our female population, brings a melancholy increase to the vice and lewdness that is now to seem rampant in every part of our town. From this class we have received no good servants for the wealthier classes in the towns, no efficient farm servants for the rural population, no virtuous, and industrious young women, fit wives for the labouring part of the community; and by the introduction of whom a strong barrier would be erected against the floods of iniquity that are now sweeping every trace of morality from the most public thoroughfares of our city.”

………….The most stupid, useless, ignorant and unmanageable set of beings that ever cursed a country by their presence… whose knowledge of household duty barely reaches to distinguish the inside from the outside of a potato.’

By mid 1849, opposition in the colonial press had mounted & the cry soon went up…..SEND NO MORE YOUNG WOMEN FROM THE IRISH WORKHOUSES! 4500 people (10% of the total population) turned out & protested against the Irish immigrants, in Sydney streets. These actions highlighted the shifting dynamics of Irish immigration to Australia.

Although Sydney and Melbourne had effectively stopped the influx of Irish girls from workhouses, smaller numbers of both male and female Irish workers continued to arrive, often mixed with other assisted migrants from England, Scotland, and Wales. Adelaide and Brisbane remained destinations for these migrants although by that stage, the good citizens of Adelaide were also starting to make rumblings of discontent about the numbers of Irish girls being sent there.

Brisbane, however, presented a completely different scenario. The town’s skewed male-to-female ratio and its chaotic environment—marked by newly released convicts, insufficient policing, excessive alcohol consumption, and tensions with Indigenous populations—created a strong demand for women. In such a context, Irish girls were seen as vital to balancing the population and supporting the community’s growth. The town administrators were not about to send any women away, recognizing the essential role they played in the social and economic fabric of the colony.

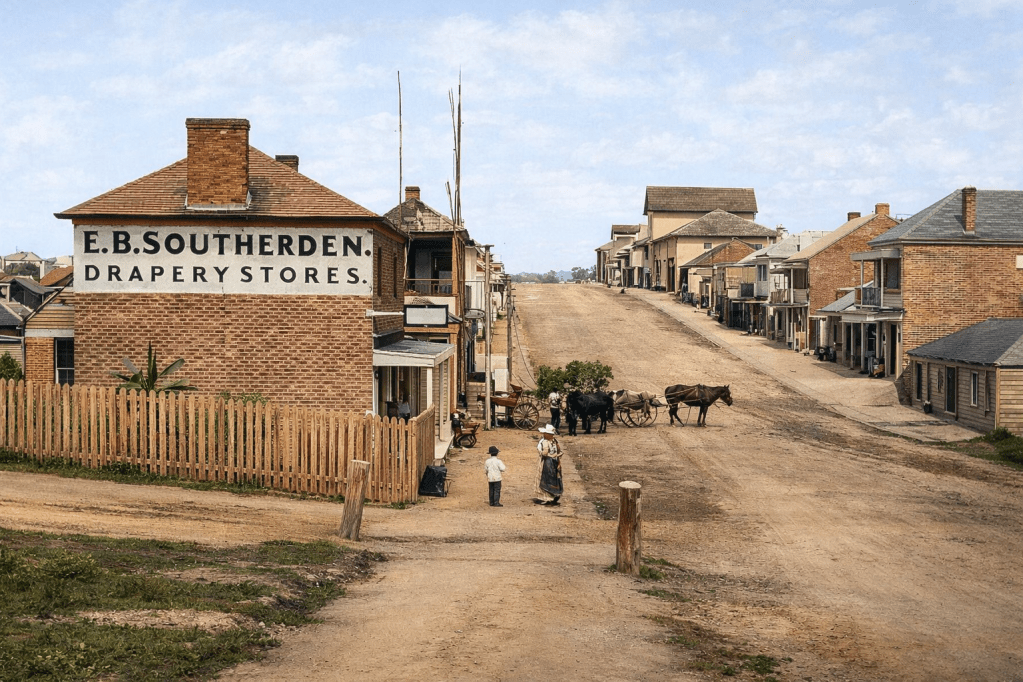

Brisbane’s “wild west” reputation underscores the challenging conditions these women faced upon arrival. Despite the town’s rough nature, the practical need for women, especially in agricultural regions, ensured that these Irish migrants would be integrated into the community, contributing to its expansion and development.

Whether or not, the Earl Grey assisted migrant scheme was a success, is a matter for other historians to debate. Grey had his own high-minded attitude to colonials. His principal means of meeting colonial demands for labour was the renewal of large-scale government-assisted emigration. And of this, the female orphan scheme was but a part.

From the perspective of the Colonial Administration, the Earl Grey assisted migration scheme initially appeared successful, addressing labor shortages in the colonies by bringing in young Irish women to work as domestic servants and potential wives. However, over time, the scheme was perceived as a means of offloading the “flotsam” of the UK population, a term that reflected the growing dissatisfaction with the quality and origins of the migrants being sent. This sentiment contributed to the eventual mothballing of the scheme by 1855. Yet, the practice of relocating impoverished Irish men and women to Australia, particularly to Queensland, continued well into the late 19th century and into the 20th century.

The Earl Grey girls were pioneers in this wave of migration, setting a precedent for the thousands of single young women who would follow them to Australia. These girls, drawn from the poorest and most vulnerable segments of Irish society, were expected to fill critical roles in the colonies, particularly as domestic workers and, eventually, as mothers of the next generation. Their employers were tasked with ensuring their physical and spiritual welfare, but this expectation was not always met. Some employers exploited the girls, taking advantage of their isolation and lack of support.

On average, it took these young women about two years to find husbands, after which many went on to have large families, contributing significantly to the population growth in Australia. Despite the hardships they faced, these women laid the foundation for future Irish immigrants and played a crucial role in shaping the social fabric of their new homeland.

Amid these challenges, the Irish girls found support from the Catholic nuns of the Sisters of Charity. These nuns provided much-needed guidance, spiritual support, and advocacy, often intervening with the colonial authorities to secure better treatment for the girls. Their efforts helped ensure that these young women, despite their difficult circumstances, could find a measure of stability and protection in their new environment.

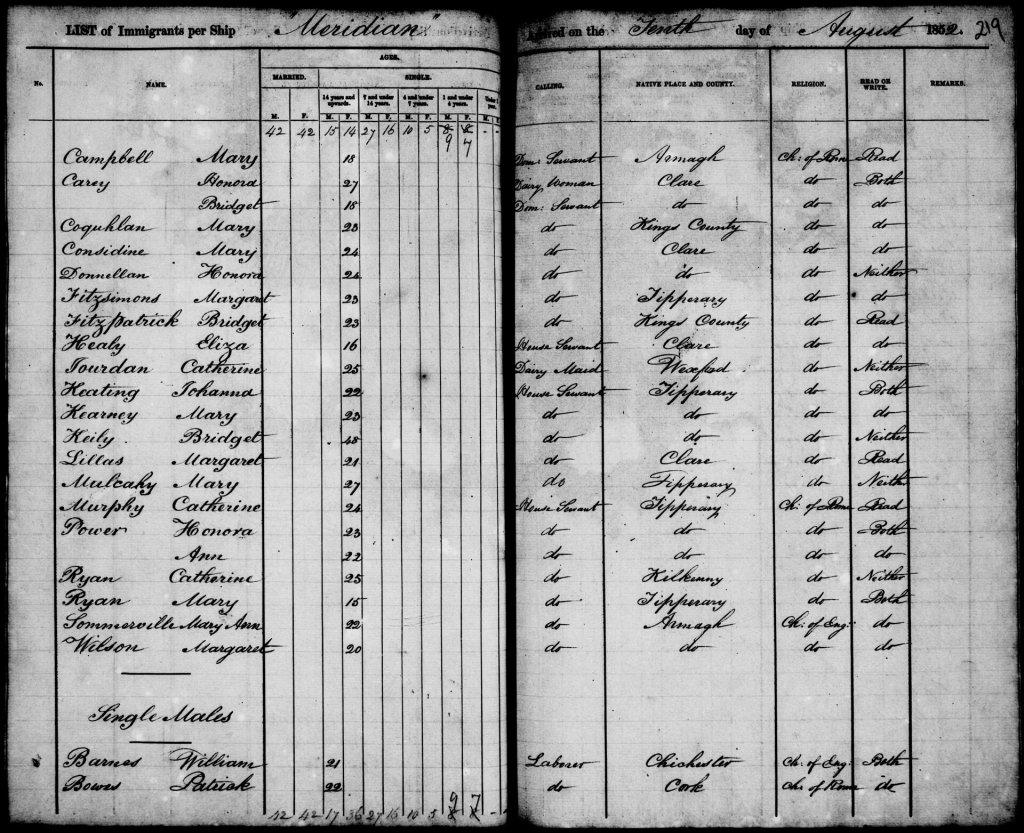

On May 1st 1852, the 579 ton “Meridian” departed Plymouth England bound for Australia, with Catherine Ryan on board, as an assisted immigrant.

Traveling alone as a young single female during the 19th century would have been an intimidating experience, especially given the treacherous conditions often faced by migrant ships. Many of these ships encountered severe weather, making the journey both physically and emotionally taxing. However, the Meridian stood out as an exception. Passengers on this vessel spoke highly of the conditions on board, which was not always the case with other ships of the time. The Meridian managed to complete its journey from Plymouth to Moreton Bay in just 100 days—a notable achievement for the era.

Voyages in the 1800s were often prolonged due to periods of calm weather, known as the doldrums, where ships could be left stranded without wind. This made the timely arrival of the Meridian even more remarkable. For the women on board, a smoother, quicker voyage would have provided some relief amid the uncertainty and challenges of emigrating to a distant land.

The assisted immigration schemes from the UK had strict qualifying conditions, requiring all migrants to be healthy, able-bodied, and of good character. Men were generally expected to be from laboring backgrounds, particularly in agriculture, while women were typically destined for domestic or farm service. The emphasis was on immediate employability and a willingness to work for wages. Migrants had to be honest, sober, and industrious, with restrictions placed on young children and those over forty.

Each migrant received basic provisions like blankets, cutlery, plates, and mugs, which they kept upon arrival. This provision hints at the general economic state of the migrants and possibly the conditions on the ships. The Meridian, carrying 243 migrants, was primarily used for passenger transport but had previously shifted convicts to Australia. The ship was small, with cramped accommodations that offered little privacy.

For many workhouse migrants, this journey was their first sea voyage, and it came after years of hardship, including poor diet and the loss of family members. The stress and trauma they endured made the prospect of starting anew in a distant land both daunting and hopeful.

The layout of a typical migrant ship in the 1850s was carefully designed to maintain order and propriety, with single males housed at the back, single women at the front, and married couples and families positioned in between. This separation was an attempt to keep the sexes apart during the long voyage.

However, with everyone living in such close quarters, it was challenging to enforce these boundaries strictly. The presence of many single young girls and women on board did not go unnoticed by the male passengers and crew. The Captain, senior officers, and the ship’s Doctor had to be vigilant to prevent any inappropriate interactions, often needing to keep a close watch to ensure the girls’ safety.

Despite these precautions, life on board had its moments of respite. In the evenings, when the lanterns were lit around the deck, the atmosphere would often become more relaxed. The girls, if they had behaved during the day, would gather to enjoy a brief escape from the monotony of ship life. They would engage in laughter, singing, dancing, and playing games, creating a sense of camaraderie among themselves. These moments of light-heartedness allowed them to reminisce about their families and friends left behind in the workhouse, providing some comfort during their daunting journey to a new life.

ARRIVAL IN QUEENSLAND – 1852

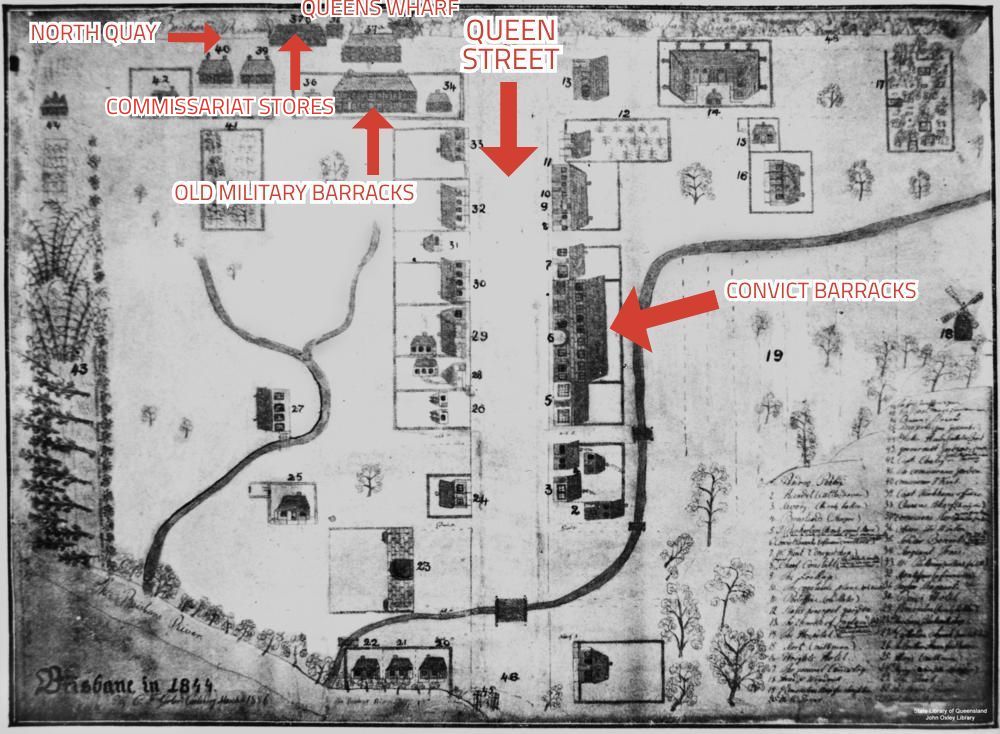

The Meridian anchored in Moreton Bay, New South Wales, on Tuesday, 10th August 1852. Upon arrival, the ship was boarded by the Immigration Agent and Medical Officer, who meticulously recorded the particulars of each immigrant from the Shipping or Immigration Board Lists and checked their health status. This process often took a couple of days, with private passengers disembarking first. It wasn’t until Friday, 13th August 1852, that the young women from the ship finally set foot in Brisbane.

To reach Brisbane, smaller, shallow-draught schooners transported the migrant passengers up the Brisbane River. They disembarked at Queens Wharf, adjacent to the Commissariat Store, below the present-day Star Casino.

In a twist of fate, the Meridian met a tragic end just a year later, in 1853, on another voyage to Australia. The ship sank near the remote Island of Amsterdam, located in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Remarkably, despite the perilous location, most of the crew and passengers survived the ordeal and were rescued by the crew of an American whaling vessel.

There were plenty of challenges faced by the young colony during the early days of free settler immigration, particularly in the context of the slow communication between the colony and London. The administrators had a tough time balancing the need for labor with the timing of immigrant arrivals due to the slow communication methods of the time. Letters took months or even years to arrive, making it nearly impossible to adjust the flow of immigrants in real time. The influx of immigrants in 1853 posed a logistical problem, as the colony’s ability to provide employment for all new arrivals was limited by the unpredictable timing of these migrations.

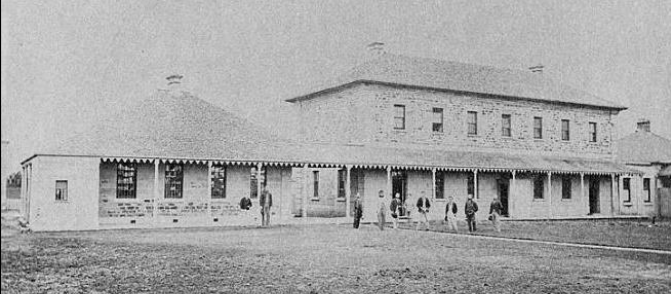

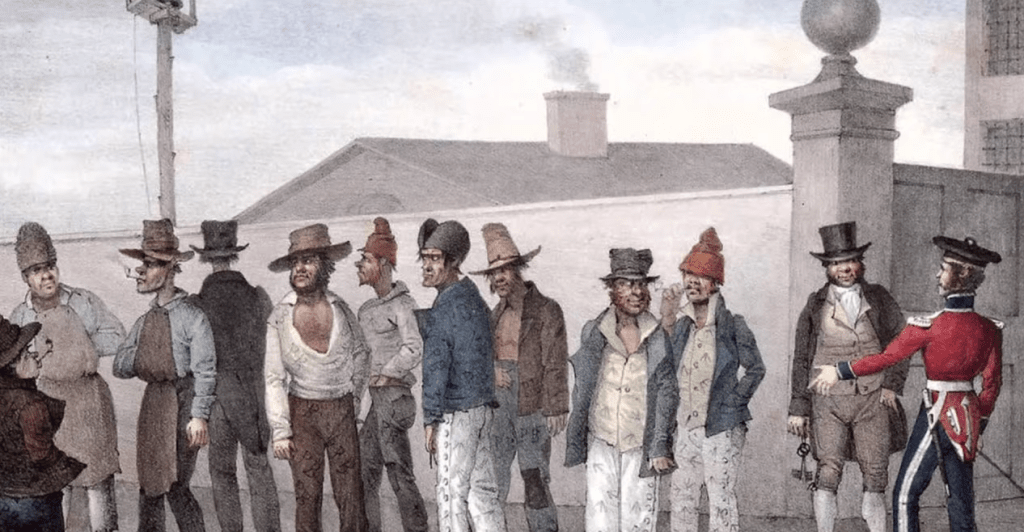

The new migrants, housed in the old Military Barracks on North Quay, were not given a warm welcome. Their treatment was reminiscent of how convicts were treated, albeit with the key difference that they had freedom of movement.

After a three-month journey, being able to walk freely around what is now Queen Street in Brisbane would have been a significant relief, even if the overall reception was less than hospitable.

Eighteen-year-old Catherine Ryan spent her first night on Australian soil in the old military barracks on North Quay, which was a relic of the earlier convict transportation period. The building faced the Brisbane River & was partly situated on the ground now occupied by the Treasury Building. It was being temporarily used as an immigration depot due to the arrival in quick succession of the four migrant ships. Catherine Ryan’s arrival in Brisbane and her first night in the old Barracks must have been a significant transition from her life in Ireland. The experience of moving from a ship, where she was surrounded by familiar faces and fellow migrants, to being separated and starting work with new employers in an unfamiliar environment would indeed have been challenging.

Catherine was one of the earlier free settlers who arrived in Queensland after assisted migration to boost the colony population was implemented after the convict era that concluded in 1842.

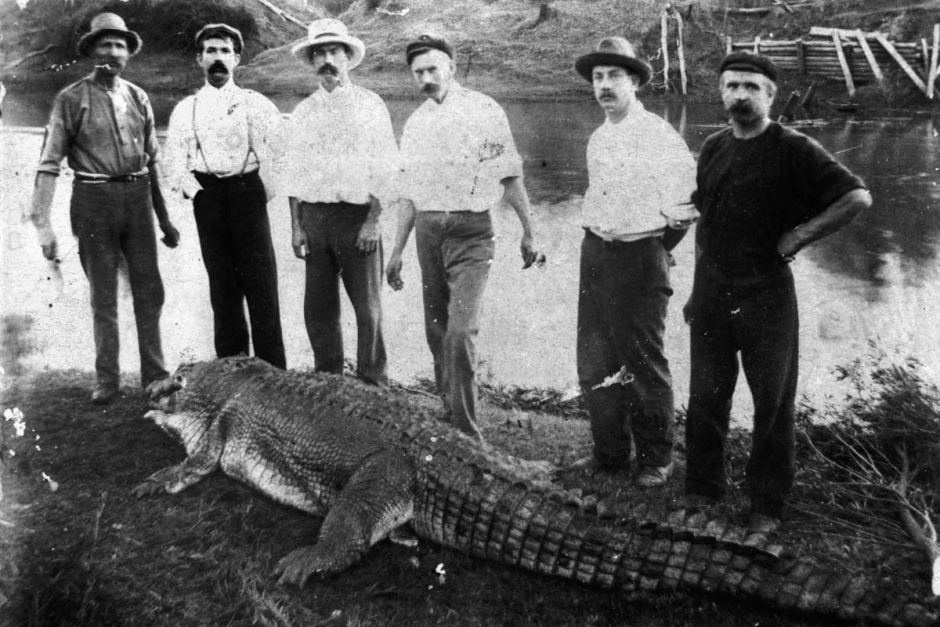

The contrast between Ireland and early Queensland was stark. The tropical climate, unfamiliar flora and fauna, and the presence of wildlife like kangaroos, snakes & other reptiles, and even crocodiles would have been overwhelming. The early settlers, especially those like Catherine, faced numerous hardships, from adjusting to the climate to dealing with the dangers of the Australian wilderness, which were very different from what they had known in Ireland.

The sense of isolation must have been compounded by the lack of detailed information about the Australian environment and the hazards that came with it. The fact that crocodiles were present in the rivers and coastal areas adds another layer of difficulty to their adaptation process. The early migrants had to navigate not only a new land but also the potential dangers it presented.

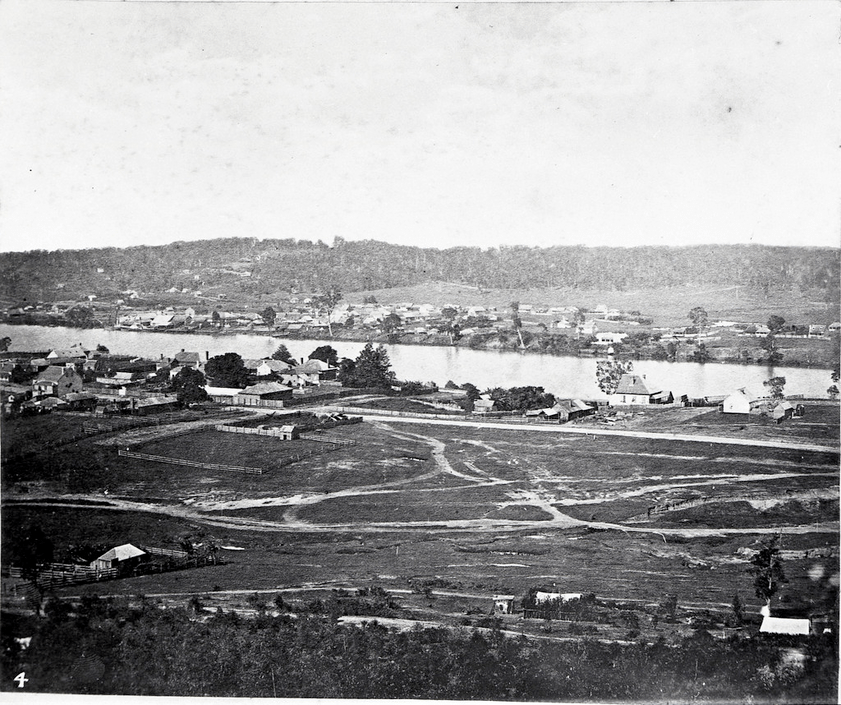

The early colonial period in Brisbane during the 1850s was indeed a turbulent time. The rapid increase in the settler population from just a few hundred in 1846 to a thriving community by 1852 brought with it a range of social and legal challenges. The influx of immigrants, combined with the existing population of convicts, ticket-of-leavers, and military personnel, created a complex and often volatile environment.

There were several Boundary Roads, actual road names, all around Brisbane well into the 1870s. Many of these roads still exist today. While some marked the boundaries of properties or councils, many served as boundary lines that Indigenous Australians were not allowed to cross after 4 p.m. on weekdays and Saturdays, and not at all on Sundays.

Even in the late 1870’s mounted troopers would ride about Brisbane after 4pm cracking stockwhips as a signal for Aborigines to leave town.

This environment shaped the early history of the city and influenced the experiences of people like Catherine Ryan as they navigated their new lives in Australia.

Early Brisbane was marked by frequent flooding, which compounded the challenges faced by its inhabitants. The lack of a bridge over the Brisbane River until 1874 meant the town was divided, making transportation and communication between the two sides difficult. This geographical split added to the town’s hardships.

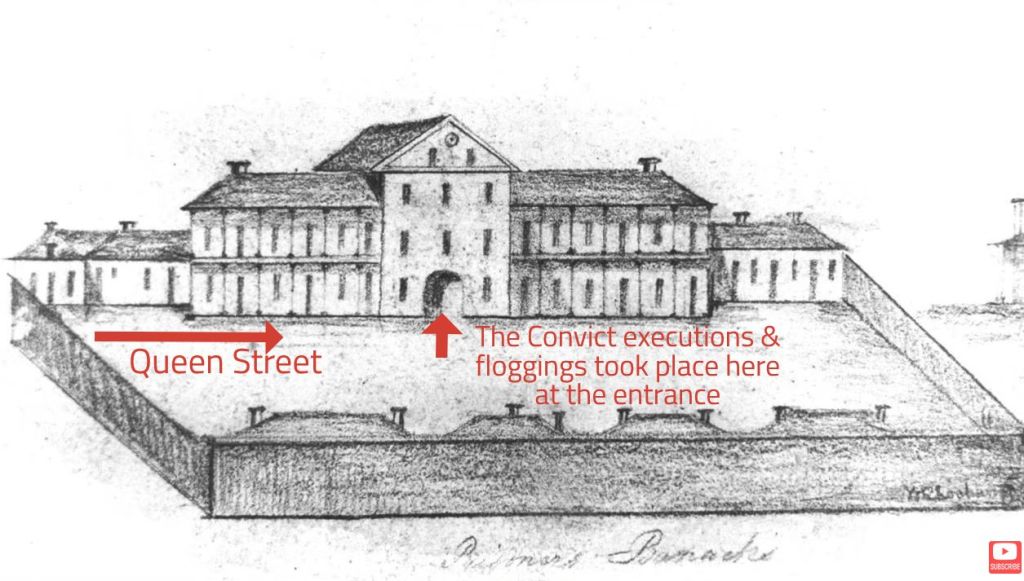

The social atmosphere in Brisbane was rough, with high levels of drunkenness and brawling. Law and order were enforced in a very public manner, with floggings being carried out on Queen Street and public hangings taking place until 1855. The sites for these public executions and punishments included the Queen Street Gaol (now the Queen Street Post Office), the Convict Barracks on Queen Street, and the Old Windmill on Wickham Terrace. These measures reflected the harsh and often brutal methods used to maintain order in the rapidly growing and turbulent settlement.

The harsh treatment of convicts during this period underscores the severity of colonial justice. Convicts who absconded faced brutal punishments, and if not executed, were given a severe flogging (300-500 lashes), which was meant to deter others from similar actions.

The early naming process for the northern outpost reflects a blend of colonial aspirations and practical considerations. The initial name “Moreton Bay Penal Settlement” aptly described its function as a penal colony. The proposed name “Edenglassie” might have seemed idealistic, but “Brisbane” was a more fitting choice, honoring Sir Thomas Brisbane, the former governor of New South Wales. His name became synonymous with the burgeoning township and helped to establish a distinct identity for the settlement.

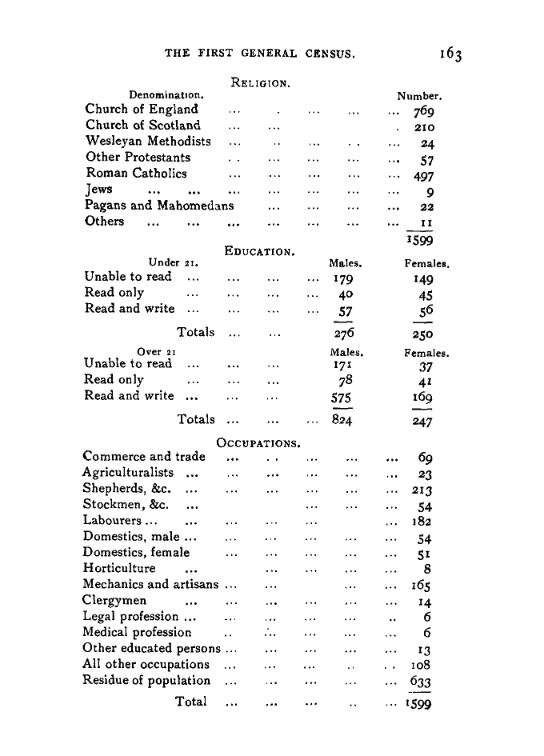

The 1846 census for Brisbane provides a detailed snapshot of the early colonial population. With a total of 1,599 people counted:

- Men: 1,123

- Women: 476

- Married persons: 489

- Born in the colony: 1,156 (primarily children)

- Free persons: 213

Among the free persons:

- Tickets-of-leave: 129 (including one woman)

- Private assignment: 8

- Government employ: 81

This distribution reflects the early demographic and social structure of Brisbane, showcasing a predominance of children born in the colony, a substantial number of men, and a smaller but significant proportion of free individuals, many of whom were in various stages of reintegration or employment within the colony.

The period following Catherine’s arrival saw a significant influx of migrants to Queensland. State Government delegations were actively recruiting people from Ireland, England, Scotland, Wales, and Germany to meet the growing needs for farmers, tradesmen, and laborers in the new colony. This effort aimed to support the expanding population and development of Queensland.

Immigration depots were established at major ports of arrival such as Thursday Island, Cooktown, Cairns, Townsville, Bowen, Mackay, Rockhampton, Bundaberg, Maryborough, and Brisbane. These depots helped manage the influx of single migrants and families arriving along the Queensland coast.

By the time of Federation in 1901, over a quarter of a million new Australians had arrived, contributing significantly to the growth and development of the colony and shaping the future of Queensland.

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1852 – 9000

Brisbane & outskirts – area pop 4000

Brisbane’s role as an immigration outlet was primarily to serve the needs of the bush, rather than to expand its own population. New arrivals were sent to work on squatters’ properties and farms rather than settle in the city. This was due to the city’s lack of demand for labor, especially for women, and the focus on supporting the agricultural and pastoral industries in the surrounding areas.

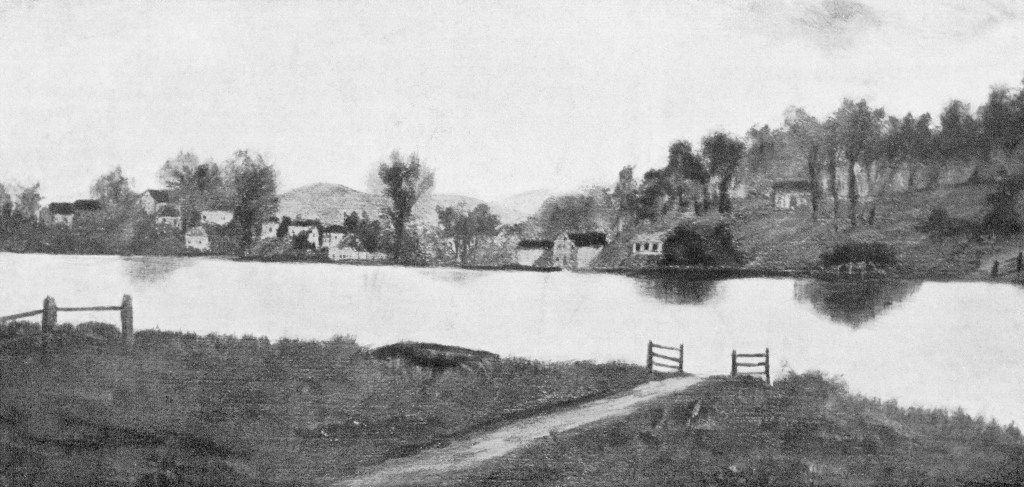

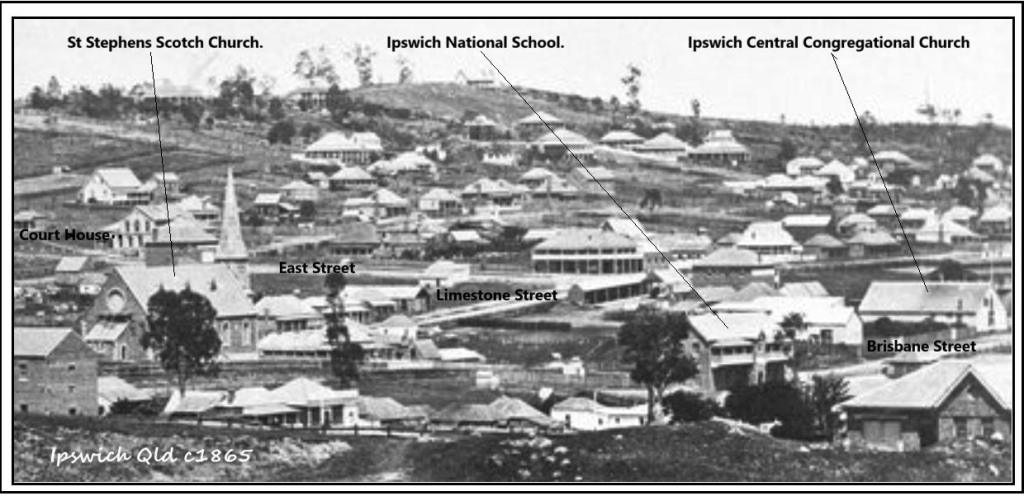

Catherine Ryan’s move to Ipswich in early 1853 reflects the broader trend of migration from Brisbane to more promising locations. By that time, Queensland was still part of New South Wales, and Brisbane was a relatively small port town with a population of about 2,000. It was still grappling with its origins as a penal settlement and the legacy of convict transportation, which continued until 1849 despite the official cessation in 1842.

Ipswich, in contrast, was being planned with a more orderly layout and had strategic advantages. It was well-positioned to support the Darling Downs wool producers and Lockyer Valley farmers. The area had begun coal mining in 1848 and was set to become a hub for intensive farming. The early planning for the first railway line from Ipswich to Grandchester highlighted its importance in the region’s development. Ipswich was emerging as a significant center, and its potential to become the capital of the future colony was recognized by many.

An interesting observation was recorded in 1852 by a contemporary author in Ipswich, who remarked: “We must observe that the Australians have a patois of their own, particularly idiomatic among the old hands—a mixture of slang, Saxon, and Aboriginal languages. There will soon be an Australian dialect, just as there is already a Yankee dialect.”

This comment, made in Queensland’s earliest colonial days, noted that the foundations of an Australian vernacular were already emerging. The author attributed this development to a blend of influences: the refined speech of high society, the strong presence of Irish English, the rougher convict dialects, and the incorporation of numerous Indigenous terms.

Even in 1852, the earliest signs of the Aussie accent were starting to appear.

CATHERINE MOVES TO IPSWICH – 1853

IPSWICH HAD A POPULATION IN 1853 OF APPROX 1000 PEOPLE

Catherine Ryan’s move to Ipswich was a strategic decision that likely offered her better employment opportunities, given the growing demand for domestic help and labor on grazing stations. The emerging class structure in Queensland, with a mix of convicts, assisted migrants, and free settlers, shaped the social and economic landscape of the colony.

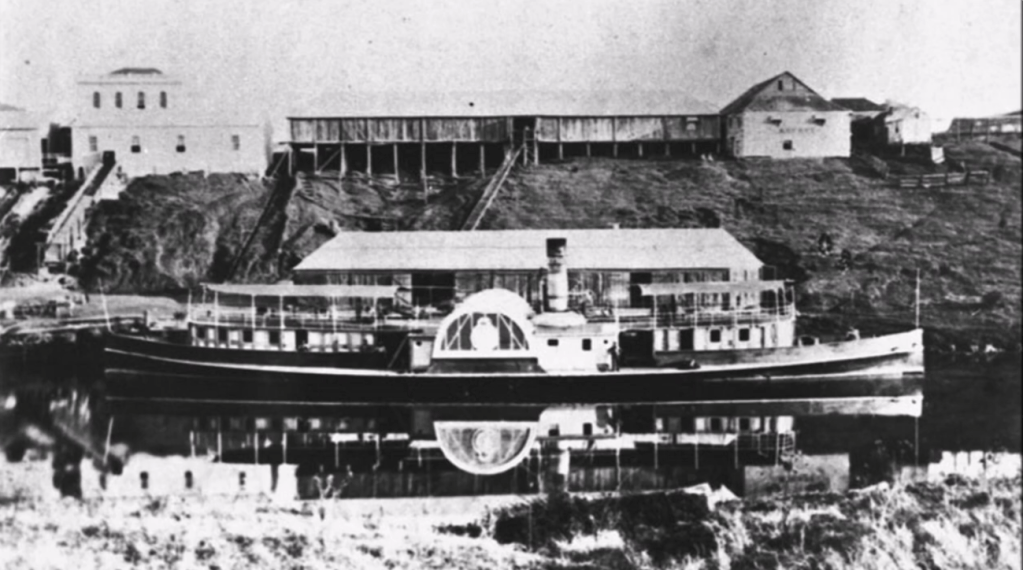

Catherine likely traveled to Ipswich by a shallow-draught steamer, such as The Swallow depicted below. The journey typically took between six and ten hours, traveling up the Brisbane and Bremer rivers, depending on the river and weather conditions.

Catherine’s relationship with Robert Bradbury is a compelling story. Robert, who had been transported for desertion from the British Army in 1832, had a turbulent history before gaining his Ticket of Leave. After being sent to Northern NSW and working at Koreelah Station, he eventually found work as a farm laborer and shepherd at Telemon Station, south of Beaudesert. His experiences as a soldier and baker before his transportation added to his diverse background.

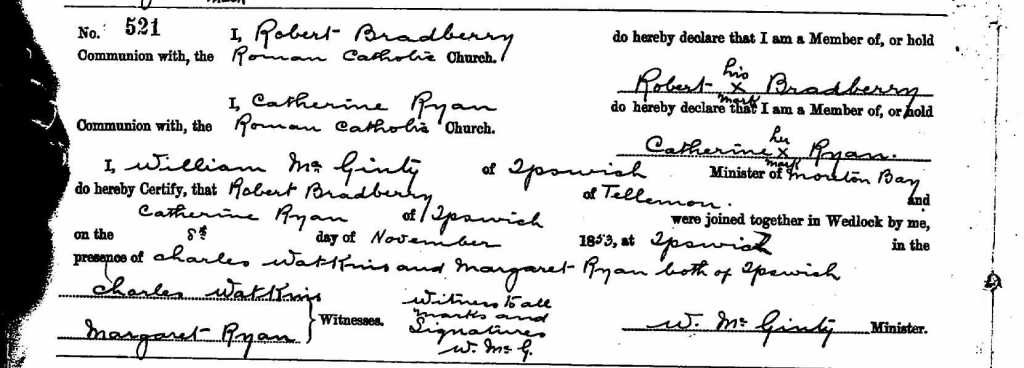

Their meeting and subsequent marriage on November 8, 1853, at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Ipswich—a modest slab hut at the time—marked a significant milestone. Catherine may have been pregnant with their firstborn child, Johanna, my great-grandmother, who was born in August of the following year. Interestingly, baby Johanna shared her name with Catherine’s mother, emphasizing the family’s strong ties to tradition. There may have been some urgency to marry, as Catherine, a devout Catholic, likely wished to avoid bringing a child into the world without the blessing of her faith. From what I understand, Robert was well into his forties, while Catherine was 19 at the time of their marriage, highlighting a considerable age difference. Their union brought together Robert, who had faced significant adversity, and Catherine, a young migrant seeking new opportunities in a growing colony. Their story stands as a testament to the complexity and evolution of relationships and social mobility in early colonial Queensland.

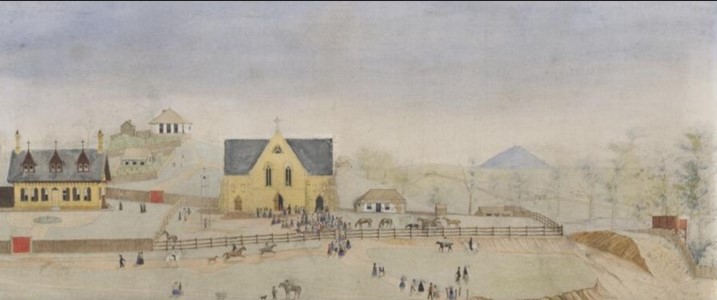

St Mary’s Catholic Church in Ipswich was originally a slab-hut timber structure, where Catherine and Robert were married in 1853 by Father William McGinty. The illustrations and photographs below depict the church’s transformation over time: first as it appeared in 1853, then a few years later in 1857, followed by the stone church built in 1859, and finally the cathedral completed in 1904.

Sidenote – Father William McGinty was a foundational & controversial figure in establishing the Catholic Church in Queensland. He played a key role in securing funding for several churches, the most prominent being the grand Gothic St. Mary’s Cathedral in Ipswich. McGinty often engaged in public disputes with parishioners, superiors, and newspaper editors.

Robert and Catherine Bradbury’s life in the Ipswich–Laidley area was marked by hard work and family growth. Robert’s employment as a shepherd and laborer on local farms provided stability for the family, and they welcomed three children during this period. Johanna Bradbury, born in Laidley in 1854, was followed by Robert Bradbury Jr. in 1857, and Mary Ann Bradbury in 1859, both born in Ipswich. The couple had also lost two male babies in childbirth in 1856 & 1861.

Their story is a reflection of the experiences of many early settlers in Queensland, who moved frequently within the district to find work and build a life in the colony. Robert’s role in the agricultural and pastoral industries was typical of the labor required to support the growing economy, and the family’s movement around the Ipswich area highlights the transient nature of work and life during this time.

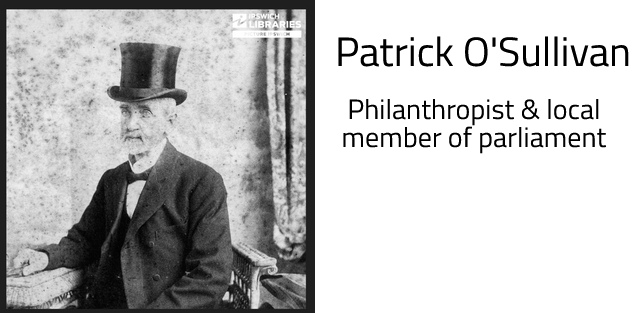

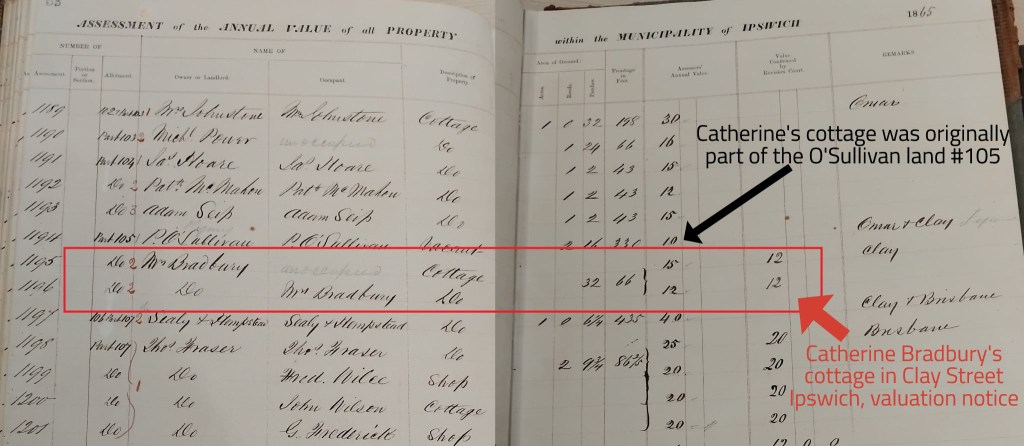

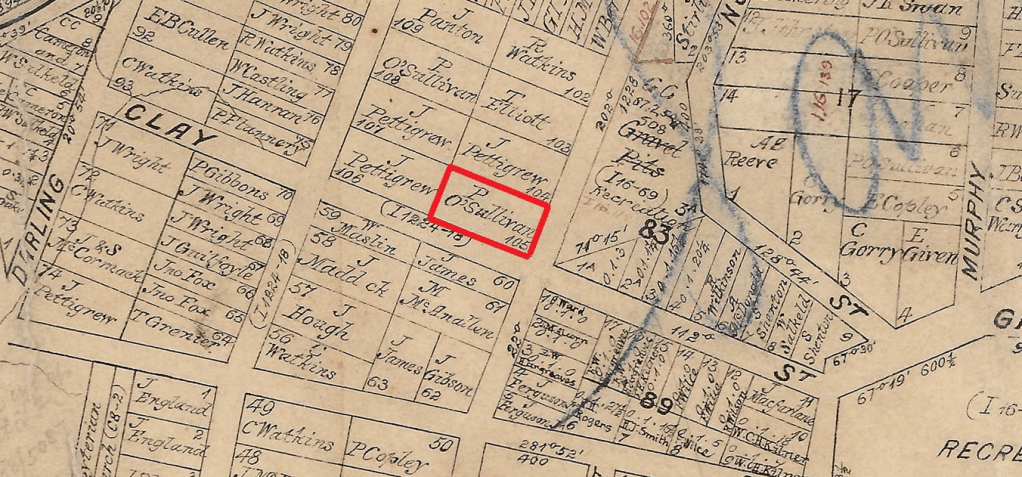

Several noteworthy coincidences occurred during this period of Catherine’s life. Around 1855, after the birth of their first child, the family moved to a house on Clay Street, West Ipswich. I believe it may have been the first dwelling built on the block, which stood on land then owned by Patrick O’Sullivan—an established local businessman, philanthropist, landowner, respected Irish Catholic, and Member of Parliament—widely known for his deep commitment to the Ipswich community. A devout Catholic of Irish descent who had originally arrived in Australia as a convict, O’Sullivan rose to prominence as a generous benefactor, actively supporting many of his constituents. I believe that Patrick O’Sullivan may have assisted Robert and Catherine Bradbury in purchasing the Clay Street property.

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1859 – 25000 (estimate at time of colony of Queensland being declared)

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1862 – 45000 (Ipswich pop 3287)

Robert Bradbury’s death in 1862 at Bigges Camp (Grandchester) marked a difficult moment for Catherine and her family. The cause of death, described as a “severe cold lasting six days,” suggests that he may have succumbed to a respiratory illness, possibly worsened by his likely habit of smoking, a common issue among former soldiers and convicts of that era. His burial in the Ipswich General Cemetery ties him permanently to the region where he spent his final years working and raising a family.

For the Robert Bradbury story, click on to the link – https://porsche91722.wordpress.com/2023/11/08/robert-bradbury-2/

At just 28 years old, Catherine faced immense challenges—illiteracy, low wages, and the overwhelming responsibility of raising three young children alone after Robert’s death. However, Queensland did offer her better employment opportunities and a sense of security that was hard to come by in her homeland.

When considering the broader context of Catherine’s life, it’s striking to realize that Robert was part of it for only a relatively short period—around ten years. They married in 1853, and he passed away in 1862.

Catherine’s deep religious faith and the support of her local Ipswich Catholic parish likely played a crucial role in helping her navigate this difficult period. Her resilience, faith, and the sense of community provided by the church would have been invaluable in providing the strength and support needed to raise her children in the absence of their father. Despite the hardships, Catherine’s life in Queensland offered a chance at a new beginning, and she would have drawn on every available resource to provide for her family and build a future for them.

As an observation, I believe Catherine was likely a strict disciplinarian with her children. This view is informed by the likelihood that she spent long periods managing the household alone while her husband worked across the district. After his death in 1862, the full responsibility of raising the family fell to her. At just twenty-eight years old, Catherine was left to raise three young children on her own, a circumstance that may have reinforced a firm approach to parenting.

Given her difficult life in Ireland and the anti-Irish prejudice she likely encountered in Australia, it seems plausible that Catherine adopted a no-nonsense, pragmatic approach to raising her family without their father—doing whatever was necessary to secure the best possible outcomes for her children. With no one to rely on, she had to fight her own battles, a reality that mirrored the broader hardships of the era.

This may also partly explain why, apart from Johanna—who married locally to Nicholas Corcoran, a farmer from the nearby Fassifern Valley—her other two children chose to move further away. Around 1876, Robert Bradbury jnr, aged approximately twenty, and Mary Ann Bradbury, aged approximately seventeen, both relocated more than a thousand kilometres from home. While this does not necessarily suggest any deep animosity between Catherine and her younger children, it does indicate a strong determination on their part to seek opportunities elsewhere. It was also around this time that Catherine severed her ties to Ipswich & moved to Toowoomba.

Catherine’s younger daughter, Mary Ann Bradbury, married Charles Thomas Regan in Mackay in 1877 and remained there until her death. Mary & Charles Regan had eight kids. Mary’s brother, Robert Bradbury Jr., had also moved to Mackay and worked for his brother-in-law, Charles Regan, in his transport business. He married Matilda Christina Albertine Discher & they had two sons. Both Robert jnr, his sister Mary & their families lived in Mackay, where they eventually died & are all buried in Mackay Cemetery.

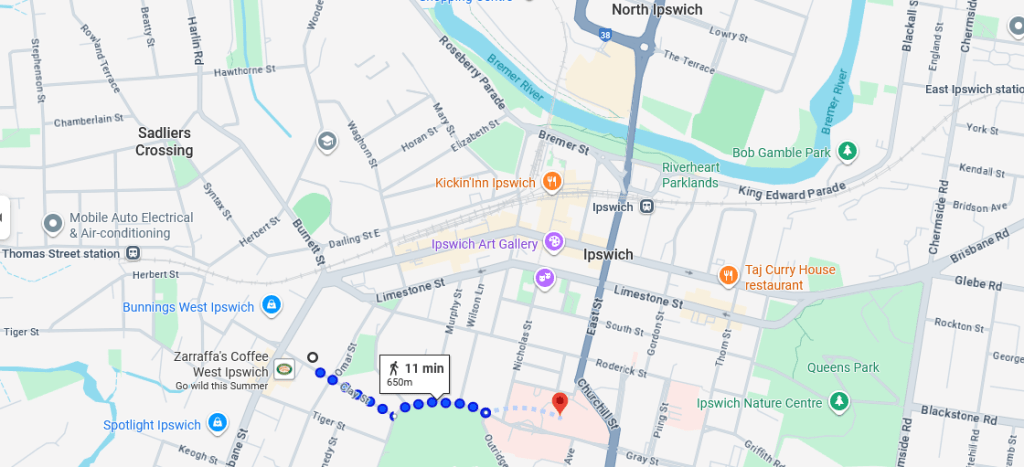

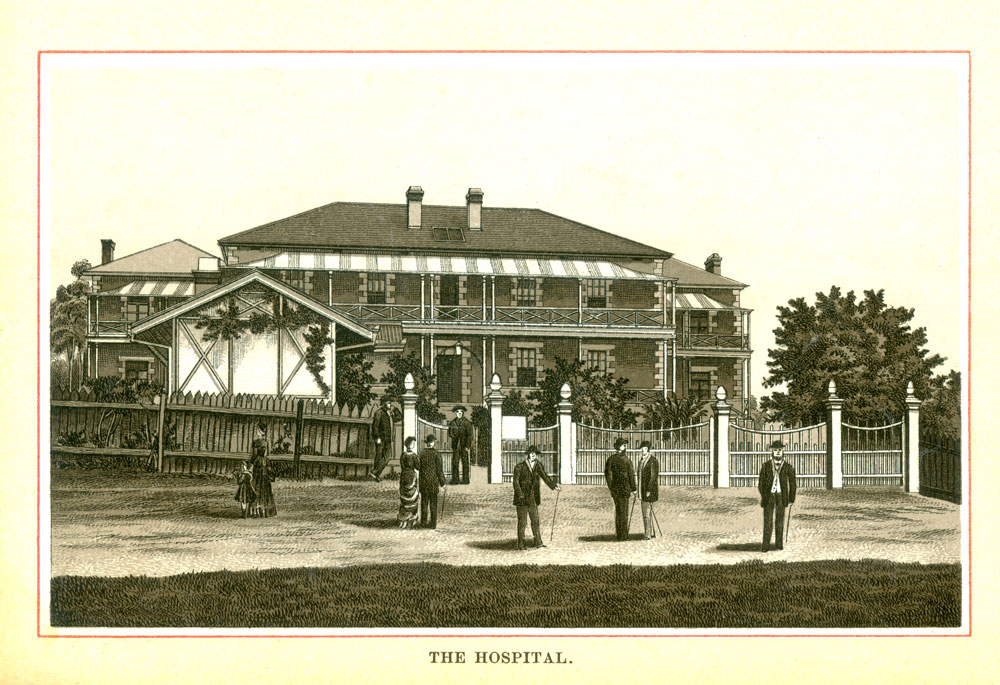

Back to our benefactor, Patrick O’Sullivan. He also played a pivotal role in establishing the original Ipswich Hospital in 1861. As a prominent figure in the early Ipswich community, I believe that he helped Catherine secure a nursing position at the hospital, which was only a 10 minute walk from her home in Clay Street. Catherine & her kids were still living at the Clay Street address at the time, in a cottage now owned by her after her husband Robert’s death, but located on a small corner block of land that was part of a larger block, that was originally owned by O’Sullivan. He was widely recognized for remembering his Irish convict roots and was known to assist many members of the local Catholic parish—Catherine was one of them.

Catherine had worked in domestic service since her arrival in the colony in 1852. Such work was abundant, as one of the original purposes of the Irish workhouse immigration scheme was to provide young women to fill the colony’s many domestic positions. However, after the untimely death of her husband, Robert Bradbury, in 1862, Catherine found herself a widow with three young children to raise. She now needed a more stable income and better qualifications to support her family. Her decision to train as a nurse demonstrates both her determination and her resilience. This choice may also have been influenced by personal tragedy, as she had previously lost two infants during childbirth.

The hospital’s proximity to her home on Clay Street offered her a practical opportunity to pursue nursing.

This profession not only enabled her to provide for her children but also aligned with the nurturing role she naturally embodied. Still, hospital work during this period was extremely demanding. Wages were meagre, shifts were long, and there was little protection for workers. If a nurse failed to report for duty, the previous shift often had to continue, sometimes extending into double or even triple shifts. Being Irish and widowed offered no leniency. Irish women in particular were expected to endure these harsh conditions without complaint, as any protest could result in instant dismissal. Prejudice against Irish immigrants was common, and employers could easily replace one Irish girl with another, given their lowly position in society.

Interestingly, when applying for nursing positions, Catherine often chose to use her maiden name. Her earlier experience working in Ipswich, including her time as a domestic servant at the hospital, likely eased her transition into nursing.

In mid-19th-century Queensland, women who wished to pursue nursing (& teaching) were required to remain single. Marriage meant automatic resignation, while widows with children were considered unreliable and were often overlooked. For Irish Catholic widows, discrimination was particularly severe, leaving them among the last to be considered for employment in many professions.

Catherine’s early life, marked by the trauma of the Irish famine, had instilled in her both resilience and a profound capacity for care—qualities that shaped her path into nursing. This career change became a turning point in her life, allowing her not only to contribute meaningfully to her community but also to secure a more stable future for her family.

By the time her daughter Johanna married Nicholas Corcoran in 1872, Catherine Bradbury was still living on Clay Street in Ipswich, maintaining her strong ties to the community while continuing her roles as both mother and nurse. At 38, she had overcome many challenges and was witnessing her daughter embark on a new chapter, all while remaining rooted in the place where she had built a life for her family.

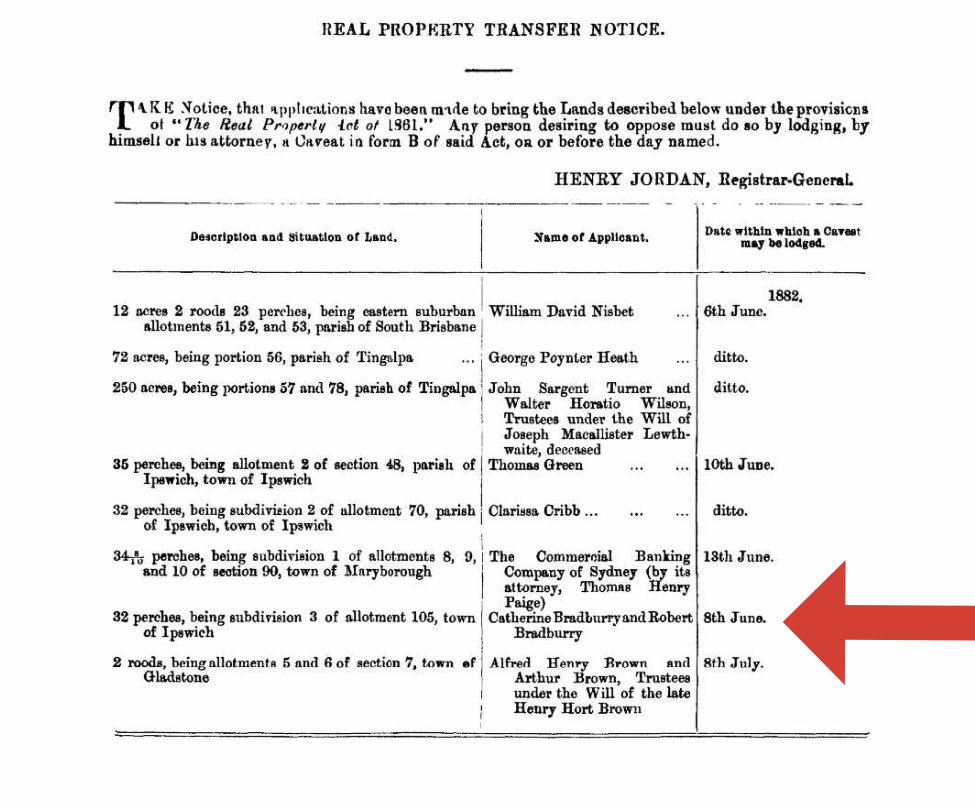

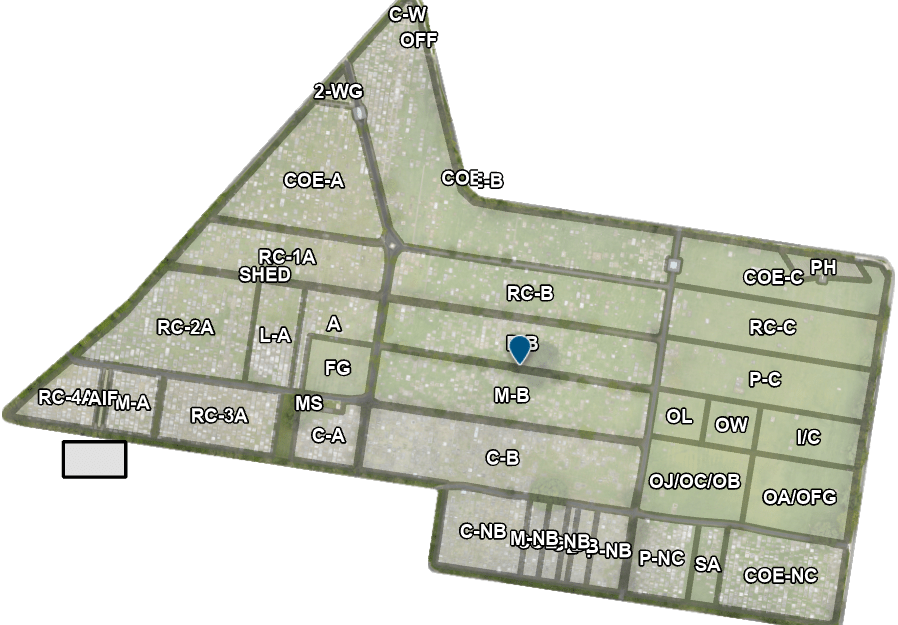

The exact location of the cottage where they resided in Ipswich, as shown on the above map, is on the left side of allotment 105. It is listed as subdivision 3.

Occasionally, when hunting down details on ancestors, you come across some peculiar or amusing anecdotes & records. The following details are taken from the minutes of 1865 meetings of the Ipswich Hospital & Benevolent Asylum.

- 2nd February 1865 – The Secretary reported that Nurse Mrs Farrell had been guilty of misconduct and had left the Institution on Sunday 29th ult. in consequence – and further that he had employed the Mrs Tomlins to replace Mrs Farrell at same wages. Appointment confirmed.

Somebody on the hospital board must have felt sorry for Mrs Farrell, because shortly after being given her marching orders, she got her job back at the hospital. There was also talk, just rumours that had come to the board’s attention, that Mrs Farrell may have been stealing hospital property. However, nothing was proven in those instances.

- 21 September 1865 – Two Nurses, Mrs Farrell & Bridget Murray were reported by the Matron as having been found intoxicated and incapable, in consequence of attending to their duties. Resolved that Mrs Farrell’s case be reserved for consideration at the end of the Month. It was resolved that an Advertisement be inserted twice in the “Courier” and the “Queensland Times” for a competent nurse.”…

- 28 September 1865 – Mrs Farrell’s case having been considered, it was resolved that her services be discontinued and that Catherine Ryan be engaged as Nurse in her place, on trial for a fortnight. The Salary being at the rate of £35.0.0 per Annum.

- 12th October 1865 – Resolved that the engagement of Catherine Ryan as Nurse, at a Salary of £35.0.0 per annum be confirmed to be paid Monthly. An agreement to be drawn up by the Secretary.

However, by 16th November 1865, the situation had changed.

- 16th November 1865 – Resolved that nurse Catherine Ryan be discharged, according to the terms of agreement & then resolved that she be re-engaged to serve as a General Servant to perform work required in the Hospital.

- Catherine had effectively been demoted, but kept on the same pay.

- 16th November 1865 – and here’s the kicker – Resolved that Mrs. Farrell be re-engaged as nurse.

- 26th November 1865 – The nurse Catherine Ryan received a cheque for £8.0.6, being for services rendered in the Hospital to this date and one Month’s pay in lieu of a Month’s Notice plus retaining her job at the Ipswich Hospital.

The decision was ultimately charitable for poor old Mrs Farrell, who was also a lady of Irish descent. At a rough guess, it’s possible that Mr Patrick O’Sullivan (remember our Irish, ex-convict philanthropist who was also a board member at the hospital) may have intervened to help both Mrs Farrell & Catherine keep their jobs.

Another interesting connection I discovered is that Mr. Charles Watkins, a hospital board member, also served as a witness at the 1853 wedding of Robert and Catherine Bradbury at St. Mary’s in Ipswich. It’s clear that members of the Catholic community in Ipswich closely supported one another.

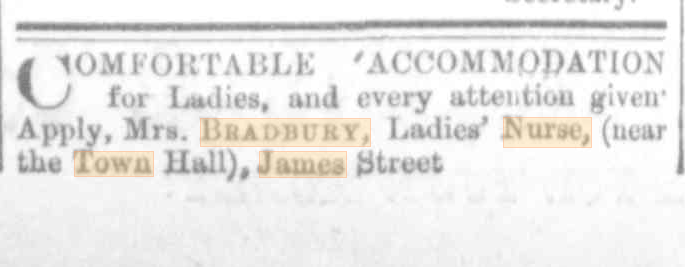

Catherine, however, found employment at the hospital through a series of different positions, which likely suited her circumstances as a widow with three young children. Evidence also suggests that she worked in a freelance capacity, taking on nursing/caring roles in various parts of Ipswich during this period. This same evidence also suggests that Catherine Bradbury worked as a nurse on Mortimer Street near the Ipswich CBD during the 1870s, likely in the years before her eventual move to Toowoomba.

So, the story had a happy ending for all the parties involved. Catherine was probably aware of the backstory of Mrs Farrell’s antics but the end result was that she got to retain her position at the hospital & hopefully, Mrs Farrell learned the error of her ways 😀.

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1872 – 134000 (Ipswich pop 5200)

Another interesting item of note in Ipswich at the time Catherine was there, showing that the sectarian religious violence between Catholic & Protestant Irishmen was still a current issue, even in Australia – “The Queensland Times reported on 19 November 1874 that there had been a riot at the Ipswich School of Arts the week before, with many of the protagonists hospitalized. The article noted that Brisbane papers referred to the “provocation given by the Orangemen (Protestants) of Ipswich and its vicinity”. The Queensland Times stated this was incorrect and that in fact “the brutal violence recorded was at all events commenced by illiterate Irish settlers from the country’, at the instigation of their more polished but equally culpable co-religionists in town.”

More than likely, Catherine would have seen to the injuries while working at Ipswich Hospital during her time there.

Another noteworthy discovery was that in 1865, when the earlier issues with Mrs. Farrell arose, Catherine and the other nurses at Ipswich Hospital earned £35 per annum. By 1876, however, wages had actually declined, with nurses receiving the modest sum of £31/4/0—a rate that remained unchanged regardless of whether they worked days, nights, or weekends. Interestingly, the position of Gentlemen’s Servant received the wage of £52/0/0 per annum and was not a medical role but rather a male domestic or attendant position within the institution. It is little wonder that nurses, who traditionally have been less inclined to protest or engage in industrial action, endured such poor treatment during that period.

To give an idea of wages in Queensland in 1876 – Unskilled labourers could earn – £50/0/0 per annum, Skilled tradesmen – £100/0/0 per annum & Steam locomotive drivers on the railways – £130/0/0 per annum. Nurses, who worked long hours received low pay rates – £31/4/00 per annum.

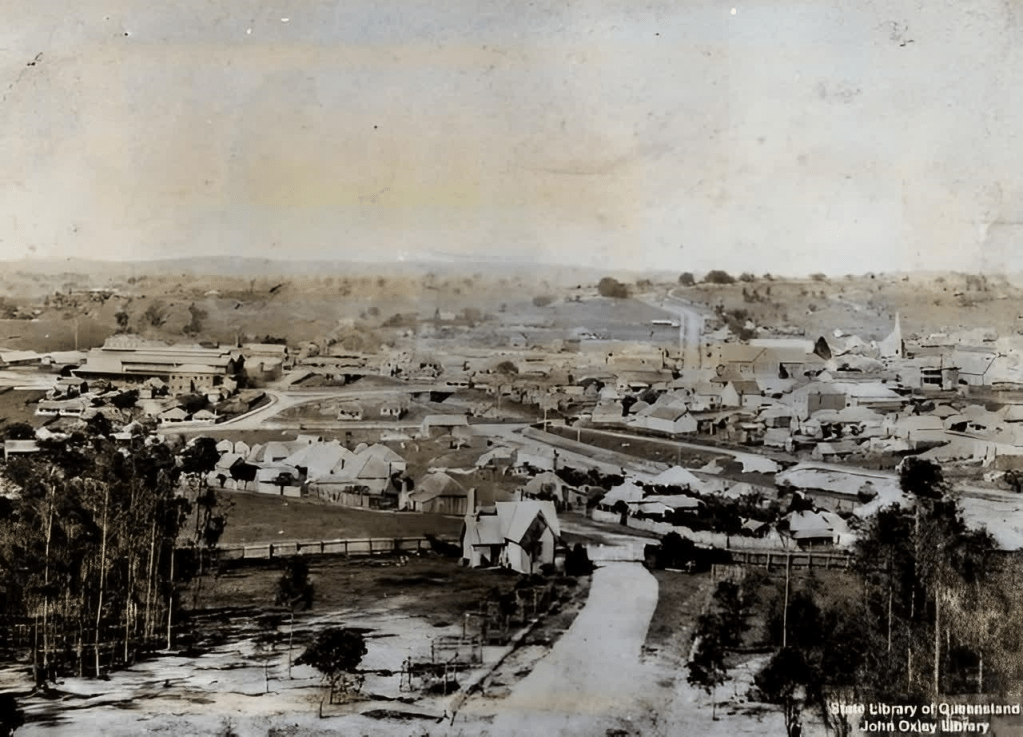

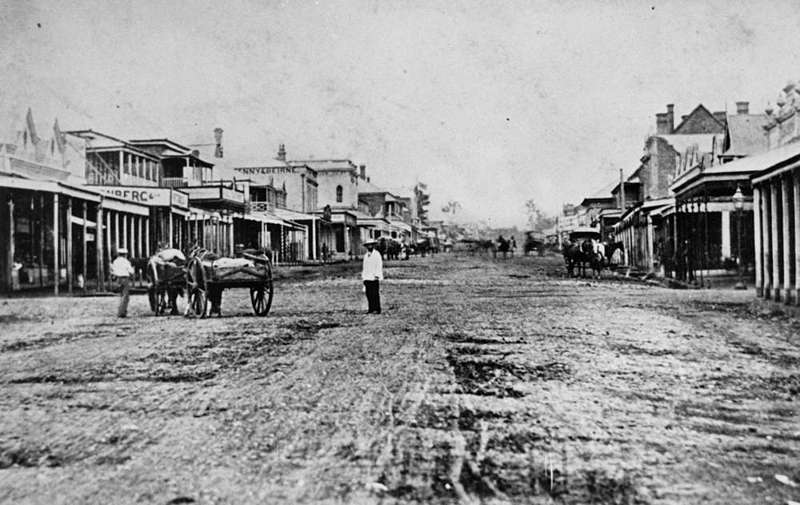

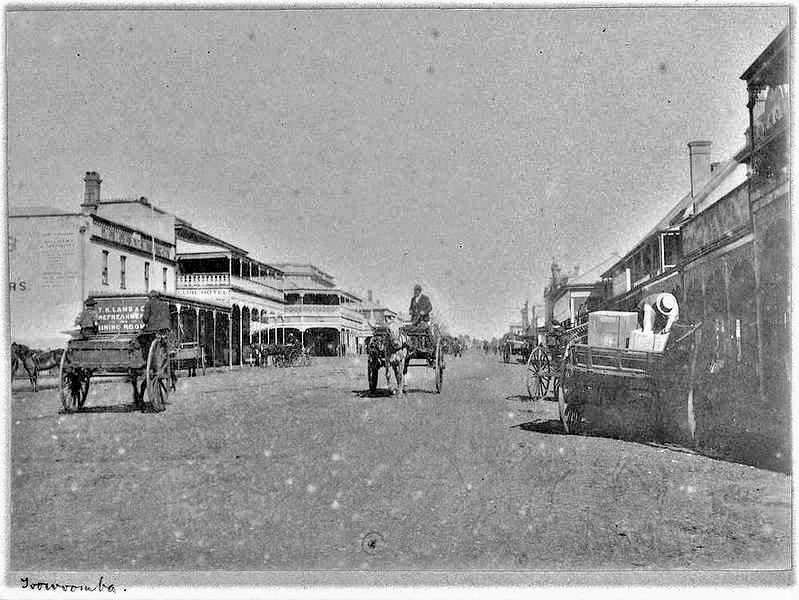

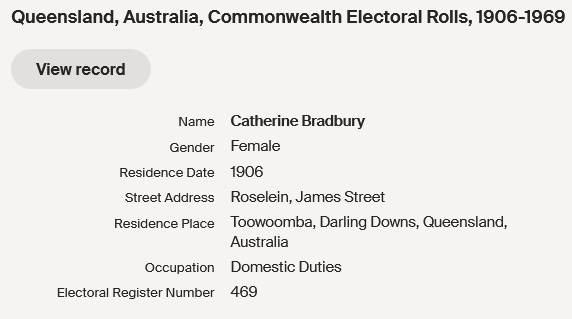

TOOWOOMBA – 1876

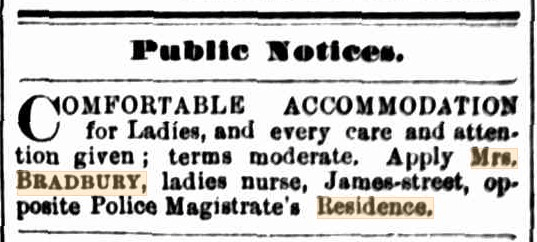

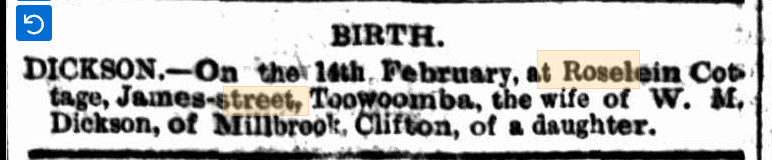

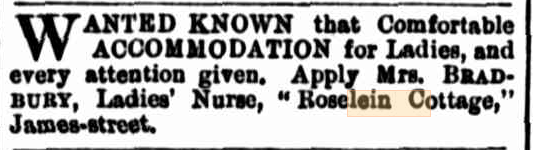

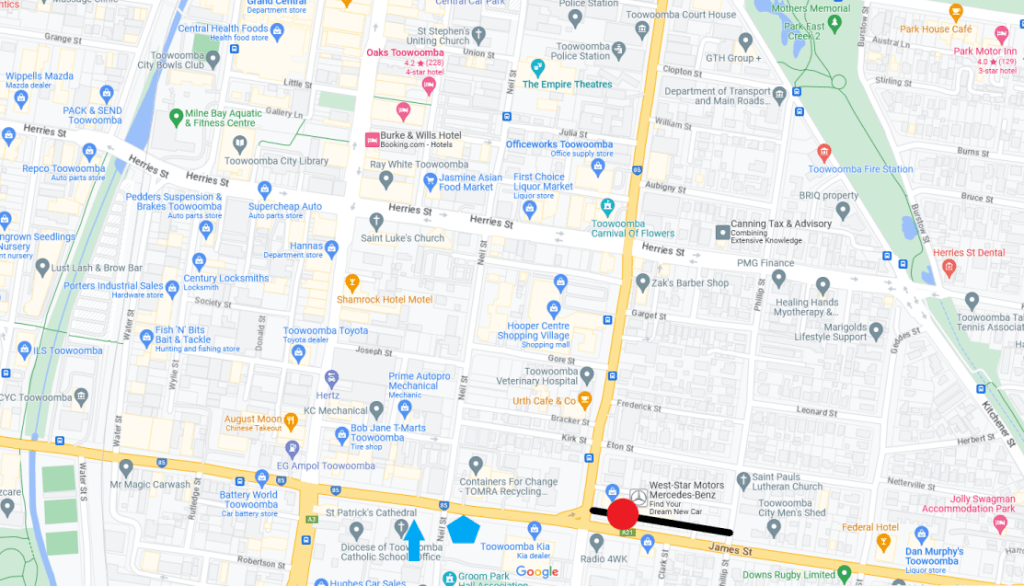

Catherine Bradbury’s move to Toowoomba in 1876 marked a significant transition in her life, as she left behind Ipswich—possibly due to the severe flooding that affected the region during the 1870s. It is likely that she took reconnaissance trips to Toowoomba before relocating permanently in 1876, most likely travelling by rail. She initially established herself as a nurse in Toowoomba, most likely at or near Toowoomba Hospital, working with a local practitioner – Dr Roberts, but later relocated to James Street, where she operated her new venture, Roselein Cottage, as a Lying-in Hospital to provide care for women in need. This move not only gave her a new sense of purpose but also allowed her to contribute meaningfully to the Toowoomba community for the next three decades.

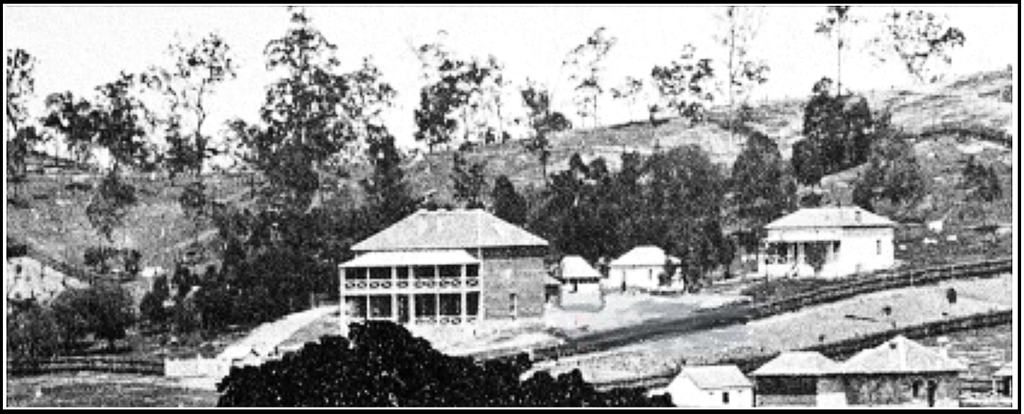

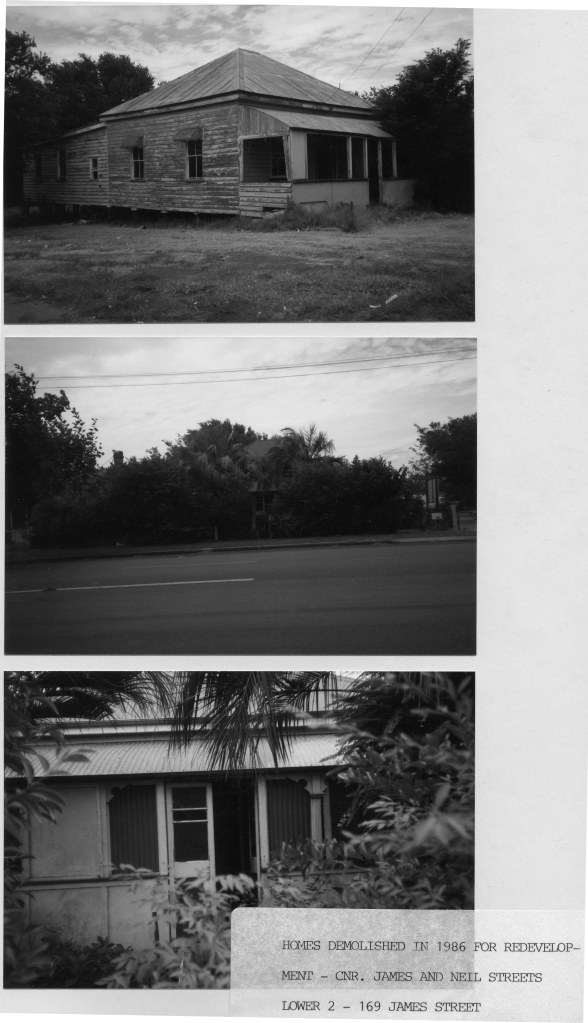

It’s fascinating to think about what Roselein Cottage might have looked like during Catherine Bradbury’s time there. A local Toowoomba historian told me that these were the homes (above) in James Street Toowoomba, prior to demolition. The fact that they were in a dilapidated condition by 1986 suggests that they had seen many changes over the years, yet they also hold a glimpse into the past. The top house in this photo group is likely Roselein Cottage.

Catherine’s hospice – Roselein Cottage would have provided an important service to the community, offering care and accommodation for women in need. The historical context of these homes helps paint a picture of the kind of environment she worked in and the living conditions of the time.

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1882 – 240000 (Toowoomba pop 7734)

Catherine Bradbury’s daily attendance at Mass at St Patrick’s Cathedral underscores her deep religious commitment and how central her faith was to her life in Toowoomba. Being so close to her residence/hospice at Roselein Cottage would have made it convenient for her to integrate her spiritual practice with her daily responsibilities.

Understanding Catherine Bradbury’s life and mindset during her 30 years in Toowoomba involves piecing together various aspects of her daily existence, interests, and the broader context of her times. Here’s a glimpse into what her life might have been like:

- Community Engagement: Given her role in operating Roselein Cottage and her daily attendance at St Patrick’s Cathedral, Catherine was likely deeply involved in her local community and church life. Engaging with parish activities, participating in church events, and contributing to community welfare would have been significant aspects of her life.

- Personal Fulfillment: Running a Lying-in Hospital and providing care for women in need would have been fulfilling work. Her dedication to this role suggests a strong sense of purpose and commitment to service, which could be seen as a personal interest or passion.

- Reading and Education: While specific details about her hobbies are not documented, many women of her era who were involved in community and religious activities often engaged in reading and education. She might have read religious texts, newspapers, or other materials relevant to her work.

- Resilience and Adaptability: Catherine’s move from Ipswich to Toowoomba and her successful operation of Roselein Cottage reflect her resilience and adaptability. Managing a hospice for over 30 years in a new town shows her ability to overcome challenges and adapt to new environments.

- Faith and Spirituality: Her daily attendance at Mass and the close proximity of her hospice to St Patrick’s Cathedral suggest that faith was a central element of her life. Her spirituality would have provided her with strength and guidance, influencing her outlook on life and her approach to her work.

- Commitment to Service: Catherine’s decision to operate a hospice and advertise for accommodation indicates a strong commitment to helping others. Her role as a caregiver and her active participation in community life demonstrate a mindset oriented towards service and support.

- Practicality and Resourcefulness: Living through the 1870s to early 1900s, a period of significant social and economic change, Catherine would have had to be practical and resourceful. The need to maintain and manage her hospice, handle the demands of her work, and navigate life’s challenges would have shaped her practical mindset.

- Social and Economic Conditions: The late 19th century in Queensland was marked by both growth and hardship. Catherine would have felt the impact of economic changes, evolving social expectations, and the development of infrastructure and services in Toowoomba. Toowoomba was viewed as the gateway to the rich and expanding Darling Downs farming and grazing region. In the 19th century, the Darling Downs was also a place where empires and reputations were being built by the landed gentry of the new colony of Queensland. It was a city on the rise—a hub of opportunity. Although Catherine likely never saw Toowoomba as a place to seek wealth, as she considered herself a humble nurse devoted to her faith and service to God, she was certainly in the right town at the right time. Toowoomba was rapidly growing, attracting new residents and industries, and she was quietly part of that transformative era.

- Health and Hygiene: Operating a Lying-in Hospital during this time meant dealing with the health and hygiene standards of the era. Her work would have involved managing these conditions and providing care in a setting that was evolving with medical advancements.

Catherine’s life in Toowoomba was marked by dedication to her work, strong faith, and a commitment to community service. Her interests and mindset were likely shaped by her experiences, her role in the community, and the broader social and economic conditions of the time.

Fast forward to my own lifetime. When I was a child & into my teenage years, I knew Catherine Bradbury’s Grandaughters – my 2 x Great Aunts -Aunty Min (Mary Anne Corcoran – lived to 100) & Aunty Hannah (Johannah Mary O’Donohue – 88) & my own Grandmother – Nana Catherine Bermingham (88). All three sisters were strict Catholics, & when I say strict Catholics, I mean, almost fanatically bigoted. As a young kid visiting their homes, it was quite the traumatic experience. The houses were filled with religious paintings & artifacts throughout all the rooms & hallways.

The local Catholic Priest in Boonah, visited weekly to Nana Catherine Bermingham’s home to do a full Catholic mass with her. I don’t say any of this, to denigrate them, but just to show the level of their religious fervour. Trust me, they took their spiritual fanaticism to another level. The homes were always in darkness. I think they all had an aversion to turning on the lights or opening the curtains. In saying that, we cared for them deeply. These three old ladies were the family matriarchs & had unfailingly carried their pious values for their entire lives. I always sensed that there was an overiding fear factor with their fervent devotion. But…then again, this was standard operating procedure for the Catholic Church. Their deep religious beliefs had been heavily instilled in them, at an early age, from their parents & grandmother.

Operating a hospice and managing the needs of those in her care would have been a full-time commitment, leaving her little opportunity for personal leisure or relaxation. Her church, as a place of spiritual solace, likely provided her with a sense of peace and connection amidst the demands of her daily life. The devotion she carried from her earlier life in Ipswich, combined with her rigorous work in Toowoomba, paints a picture of a life centered around service, faith, and resilience.

St Patrick’s Cathedral (blue arrow). In the late 1800’s, the original Toowoomba Town Hall (blue pentagon) was located opposite St Pat’s on the south eastern corner of James & Neil Streets.

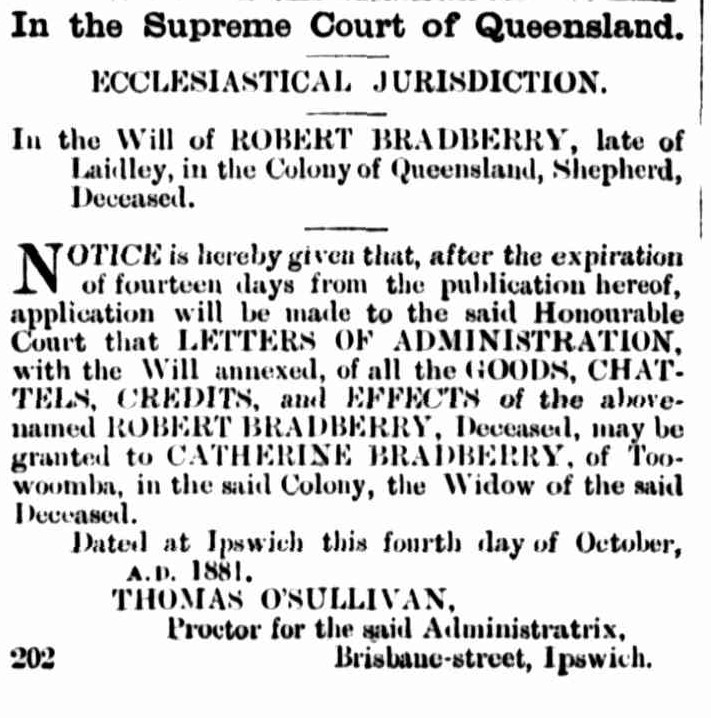

In 1881 probate on Roberts’s will was granted to Catherine.

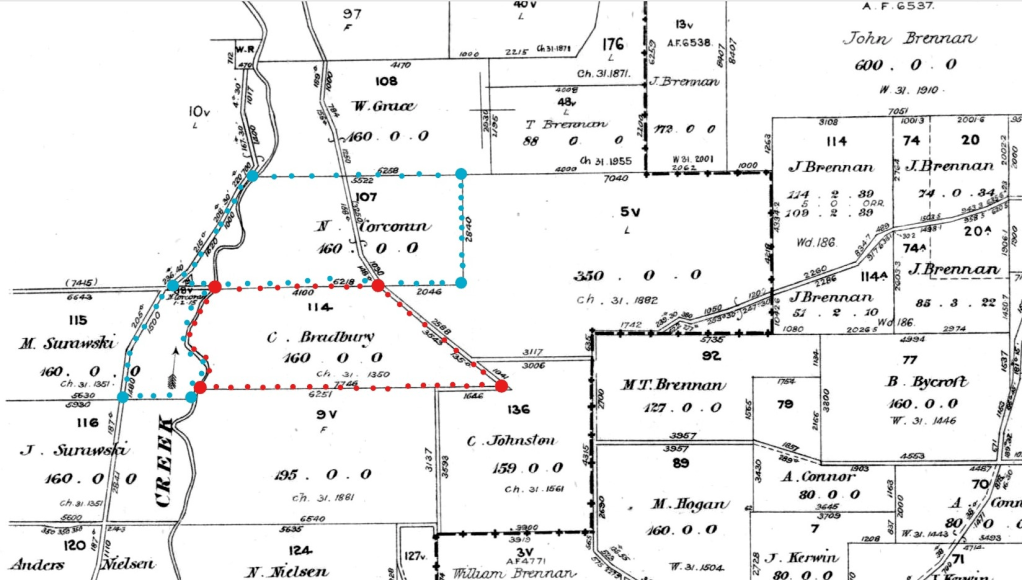

In 1886, Catherine Bradbury purchased 160 acres of land with the proceeds of her husband Robert’s estate. She bought lot # 114 marked in Red on the above land map, directly beside Johanna (her daughter) & Nicholas Corcoran’s property, “Rockmount”at Croftby, in the Fassifern Valley. It’s possible there was a falling out between Catherine & her two younger children – son, Robert jnr & daughter, Mary Anne.

It seems that Catherine’s purchase of land near Nicholas & Johanna Corcoran’s property and the distance between her and her younger children might indicate a complex family dynamic. While Catherine’s decision to invest in land near Johanna could reflect a desire to stay close to her daughter and her family, the absence of communication or records with Robert Jr. and Mary Anne suggests there might have been some estrangement or unresolved issues.

Family relationships can be intricate, especially with the added pressures and challenges of life in a developing colony. The reasons behind Robert Jr. and sister Mary Anne’s distance from their mother Catherine Bradbury might never be fully known, but the available evidence points to a significant shift in family connections during this period. Robert Bradbury (Jnr) did keep in contact with his sister, Johanna, in later life, as can be seen in photos of him with her on a visit to Rockmount.

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1892 – 410000 (Toowoomba pop 13500)

QUEENSLAND POPULATION COUNT 1902 – 511000 (Toowoomba pop 14900)

Catherine’s strong Irish brogue and her move to her daughter Johanna’s farm in the Fassifern Valley in her later years, at age 72, add a poignant touch to her story. It’s remarkable how certain aspects of one’s identity, like an accent, can persist even through significant changes and challenges in life. Her transition to living with her daughter’s family in the Fassifern Valley after losing her sight highlights the importance of family support and the deep connections that remained strong despite the physical and emotional distances.

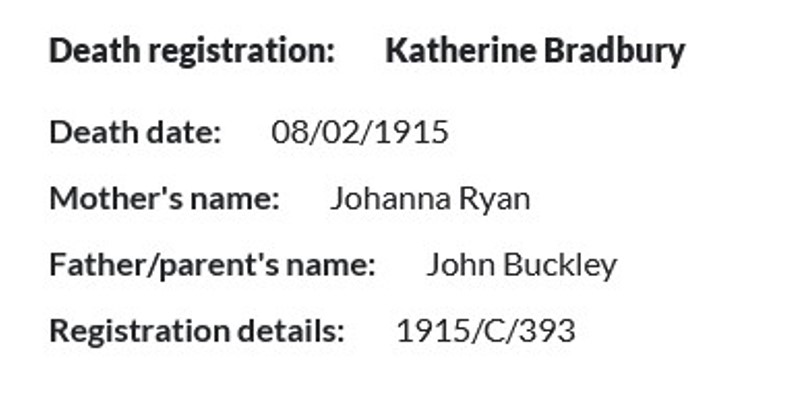

Catherine Bradbury died on 8th February 1915 at the age of 81, at her daughter and son-in-law’s grazing property, “Rockmount,” located in Moogerah near Croftby in the Fassifern Valley, Queensland, Australia. I have no way of knowing what her quality of life was like at the time of her passing. According to her death certificate, she succumbed to senile decay, heart failure, and exhaustion—a common description on death certificates for elderly people at the time. However, upon reading the listed causes of her death, I have no doubt she was utterly exhausted after living an extraordinary life.