Reading time 28 minutes

Writing an article about someone with minimal information can be quite challenging. When beginning ancestry research, the goal is always to ensure accuracy and maintain detailed, precise records. However, while cross-referencing records across the numerous genealogy websites available today, it becomes evident that some people gravitate toward exciting, mysterious, or intriguing details about ancestors—details that, unfortunately, are often incorrect. This can lead you down the wrong path, connecting to unrelated individuals and steering further away from the truth as you delve deeper. This has happened to me more times than I can count. It’s essential to stay open-minded and be prepared to admit when you’ve made an error. The key lies in methodically and factually connecting the dots. For instance, it seems that half of Australia’s population today claims to be descended from the family of the infamous bushranger Ned Kelly. However, since Ned Kelly never had any children of his own, such claims of connection to him or his relatives are highly tenuous.

Records must be verified and cross-checked multiple times to confirm their relevance to the person being researched. Occasionally it feels as if the individual you’re trying to trace deliberately avoided leaving a paper trail or simply led a quiet, unremarkable life that left little evidence behind.

Many historical records have also been lost or destroyed by calamity. Ireland, for example, suffered substantial losses of family records through fires, famine, war, and civil unrest. Many people born or who died during the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1852), for instance, were never formally recorded.

That fact is both sad and tragic. Countless people were born, grew up, often married, raised children, and worked quietly for decades without becoming celebrities, war heroes, explorers, or otherwise notable — and yet their lives have largely vanished from the documented records. Records were not kept, were misrecorded, or were later misplaced, lost, or destroyed; for genealogists, this is why many family trees encounter what people in this hobby call a “brick wall.”

A brick wall happens when you cannot find any further records that push your research back beyond the last known relative on a particular lineage. It’s frustrating and common — an unavoidable reality of genealogy.

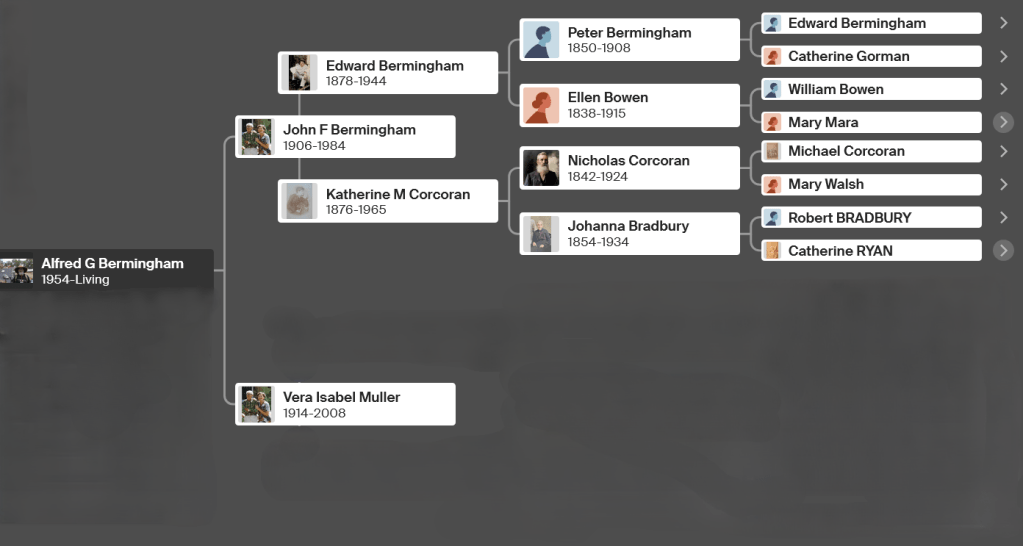

With that in mind, I can trace our family’s Bermingham line back only to the earliest verifiable ancestor—someone who can be reliably documented as having lived in the Carbury area and surrounding districts of County Kildare, Ireland, and who was born in 1850 & died in Australia in c1908.

Bermingham is the Gaelicized version of “de Bermingham”. The Irish form of the name, MacFeorais or MacPheorais, derives from Pierce de Bermingham (died 1307). The first recorded Bermingham in Ireland, Robert de Bermingham (son of William), accompanied Richard de Clare, or “Strongbow,” during Henry II’s conquest of Ireland in 1172. Upon arrival, Robert de Bermingham received “an ancient monument, valued at 200 pounds, on which was represented in brass the landing of the first ancestor of the family of Bermingham in Ireland.” The family initially settled in Galway in the west and later in Kildare in the east.

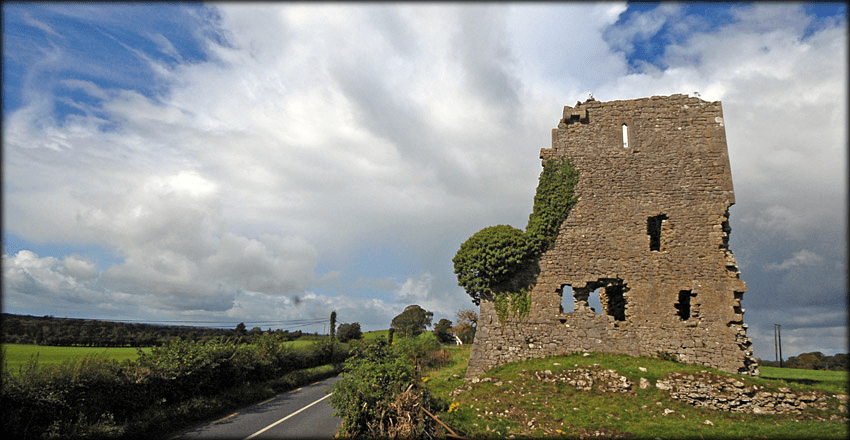

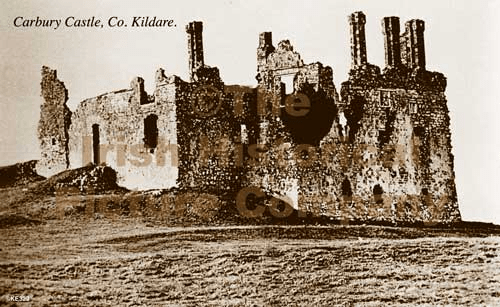

Myler de Bermingham founded the town and abbey of Athenry, Galway, in 1240. Pierce de Bermingham, mentioned earlier, held a castle at Carrick in County Kildare and is historically infamous for murdering more than twenty members of the O’Connor clan at a feast he hosted in 1305.

Our Bermingham family heritage appears to trace back to Carbury, County Kildare, suggesting that descendants of this branch may have remained in the region until the birth of my great-grandfather, Peter Bermingham, in Ireland in 1850. However, I cannot confirm this connection. Irish family records from the time of the Great Famine (1845–1852) are notoriously difficult to use for genealogical research, as many crucial documents, including census data, were destroyed. Apart from sharing the Bermingham surname and finding the family history fascinating, I have found no conclusive records linking us to these earlier Irish ancestors.

The first specific mention of Carbury Castle dates to 1234, when a mandate was issued to Hugh de Lacy, Earl of Ulster, instructing him to give seisin (legal possession) of the castle to the messenger of Gilbert, Earl of Pembroke. This action followed the war between the King and Richard, Earl of Pembroke. In 1249, the King instructed the Justiciary to grant Margaret, Countess of Lincoln and wife of Walter, the late Earl Marshall, seisin of the castles of Kildare and Carbury.

By the 14th century, Carbury Castle came under the control of the de Bermingham family, who remained prominent over the centuries. In 1319, John de Bermingham was created Earl of Louth but met a grim fate in 1329 when he was killed during a siege of his castle at Braganstown by local gentry. In 1368, a parley between Irish and English forces occurred in Carbury. The Berminghams exploited the situation by seizing Thomas Burley, Prior of Kilmainham and Chancellor of Ireland, along with John FitzRichard, Sheriff of Meath, and others. The Chancellor was later exchanged for James Bermingham, who had been held “in handcuffs and fetters” in Trim Castle.

For his notorious act of murdering over twenty members of the O’Connor clan in 1305, Pierce de Bermingham earned the title “The Treacherous Baron.” Lord Richard de Bermingham achieved a significant military victory at the Second Battle of Athenry in 1316. Two years later, Richard’s cousin, John, Earl of Louth, defeated Edward Bruce at the Battle of Faughart in 1318, ending Bruce’s attempt to claim the High Kingship of Ireland. Tragically, John and over 150 of his relatives and guests were murdered in the Braganstown Massacre of 1329.

The peerage title of Baron of Athenry (also known as Lord Athenry), one of the oldest recorded noble titles in Ireland and Britain, was held by the Berminghams of Galway from their arrival in Ireland until 1799. Thomas Bermingham, the last Baron of Athenry and Earl of Louth, passed away in 1799 without a male heir, rendering the title extinct. Similarly, the title Earl of Louth, which was held by John (until 1329) and later Thomas Bermingham, became extinct upon Thomas’s death.

Between 1800 and 1830, descendants of the Bermingham family made several appeals to the House of Lords to re-establish the Baron of Athenry title. However, these appeals were unsuccessful, as no direct male lineage could be conclusively proven.

After learning about the Bermingham family’s medieval history, I can’t say I’m eager to claim definitive links to that lineage—they seem like a rather unsavory crowd. However, the fact remains that our Bermingham family heritage is rooted in Carbury, Kildare. I suspect that descendants of the family mentioned above may have remained in the Carbury area up until the time my great-grandfather Peter Bermingham was born in Ireland. That said, I cannot substantiate this connection. Aside from sharing the Bermingham surname and finding the history coincidentally intriguing, I’ve uncovered no firm records linking us to earlier relatives in Ireland.

What I do know is that my great-grandfather, Peter Bermingham, was born in Carbury, Kildare, Ireland, around 1850, during the Irish Potato Famine. His parents were Edward (or Edmond) Bermingham and Catherine Gorman.

Carbury itself had long-standing ties to the Bermingham family, whose presence in the area stretches back nearly a thousand years.

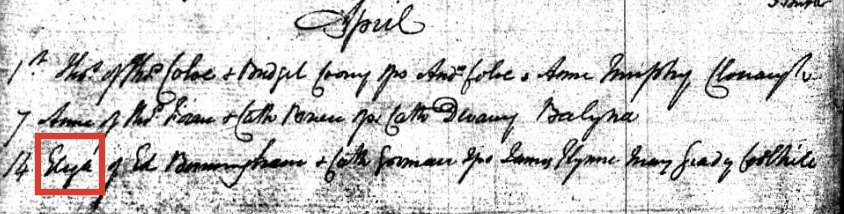

I have discovered a possible birth record for Peter, dated 14 April 1850, which links him to his parents, Ed Bermingham and Cath Gorman. The timing aligns with what I know about his birth, although the record contains some uncertainty: the Christian name listed does not appear to be Peter. The AI-generated writing translation lists the Christian name as Eliza, but upon closer examination, I’m not entirely sure that’s correct.

However, another consideration is that the Irish (or Gaelic) word for “son” is stocaigh—or possibly an abbreviation of it—it’s conceivable that a linguistic nuance may have contributed to this discrepancy. I have consulted a Gaelic writing expert, who has suggested that the recorded name could be a derivative of Peter, such as Peadar, Petrus, or, most likely, according to their analysis, Petr.

The experts also noted that the handwriting follows the old looped script commonly used by Irish parish priests in the 1840s and 1850s. The more I study it, the less certain I become. Another factor to consider is that, during this period, Ireland was in the depths of the Great Famine, and many births and deaths went unrecorded. Eventually, you reach a point where you’re grasping at straws. The matter remains unresolved; however, this record is the only one that closely matches Peter’s date of birth, which aligns with the limited later records found in the passenger shipping log and his marriage certificate.

So, I guess the big question is: Did our Peter Bermingham descend from the original medieval Bermingham family? Ok, so here’s what we know & can verify.

The Berminghams in County Kildare—bearing names such as Edward, Peter, John, and Francis—appear in parish and land records of local families throughout the 1800s.

The Kildare Berminghams were a cadet branch of the broader Anglo-Norman Bermingham family, originally associated with Athenry, Dunmore, and Carbury. A cadet branch refers to a junior line of a family, typically descended from a younger son of the main patriarch. This background suggests that Peter Bermingham likely descended from the tenant Bermingham line in Kildare rather than from the titled branch.

To offer a modern comparison, I will use the descendants of the late Queen Elizabeth II because her family provides a familiar example. Queen Elizabeth II’s first child, Charles, became King; Princess Anne is a lesser-known royal; the third child, Andrew’s reputation speaks for itself; and then we reach Prince Edward, the youngest. Few people know much about Edward — he is, in many ways, the forgotten member of the royal family.

In five hundred years, Prince Edward’s descendants would be considered a cadet branch: still connected to Queen Elizabeth II, but only distantly, with the link reduced to a faint genealogical thread. Likewise, our family appears to descend from the working-class line of the Berminghams rather than their aristocratic cousins.

Several of these junior branches survived into the 18th and 19th centuries in Kildare and Meath, long after the Athenry line had died out.

So, the closest answer we are going to get to the question is yes, distantly. To be realistic, we’re in no hurry to return to Ireland to claim any titles, castles, or estates—which, in any case, no longer exist. Our working-class farming ancestors were never in line to assert even the most tenuous connection to the original peerage branch of the Bermingham family, beyond merely sharing the name & possibly some DNA.

Peter Bermingham was born in Ireland in 1850, during the final and most devastating years of the Great Famine. I have not been able to find any records explaining what happened to his parents, Ed and Cath (Gorman) Bermingham. They may have died during the famine, or Peter may have been placed in a workhouse as an infant — the truth is uncertain. What is known, however, is that he survived, reached adulthood, and eventually left Ireland for Australia in 1874.

Carbury, like the rest of Ireland, was deeply affected by the Great Famine through starvation, disease, and a sharp population decline. The Athy workhouse provides a stark example of these conditions: it became severely overcrowded, which led to widespread illness and many deaths. The famine also triggered increased emigration from the county, as well as significant hardship that sometimes resulted in food riots, although conditions were less extreme than in the western regions.

The population of the Athy workhouse fell by an estimated 1,036 people during the famine years, with many of these losses likely due to disease or famine-related deaths. Between 1845 and 1850, the workhouse recorded 1,205 deaths, and these individuals were buried in unmarked graves. It’s possible that Peter’s parents may be two of them but unverifiable. As an infant, Peter may have been a workhouse orphan, although I have no facts to back this up, as the Athy Workhouse records around 1850-1875 no longer exist. After the famine, Carbury itself saw rising emigration as younger people left in search of work and relief from worsening conditions.

Overall, the famine brought widespread poverty and desperation. The collapse of the potato crop and subsequent food shortages caused severe hunger and malnutrition, and despite local relief efforts, the available aid was nowhere near enough to meet the overwhelming needs of the starving population.

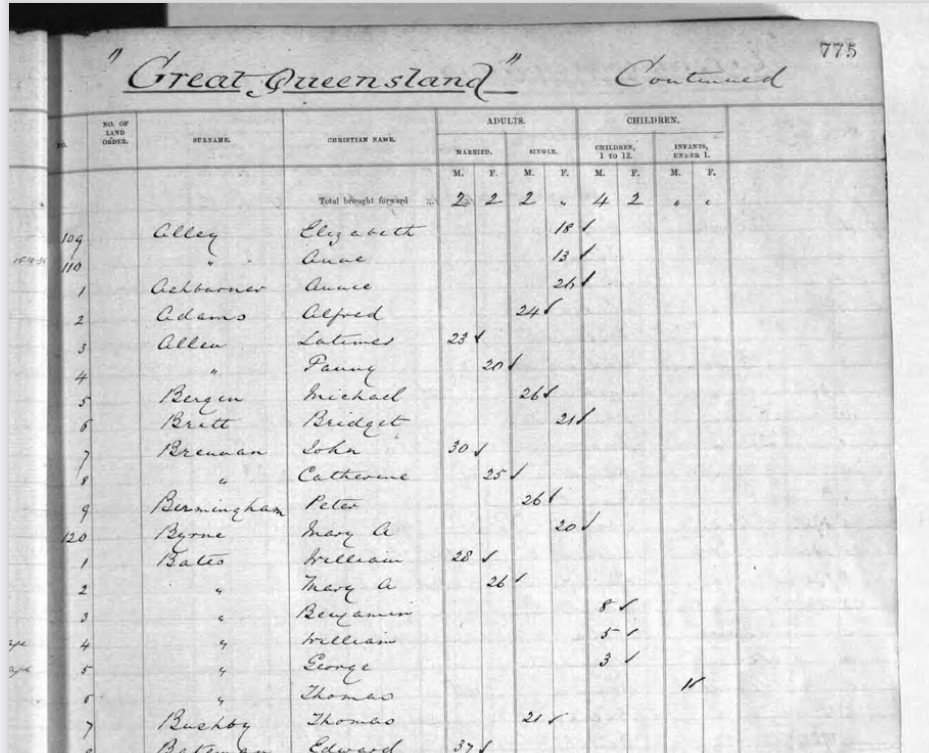

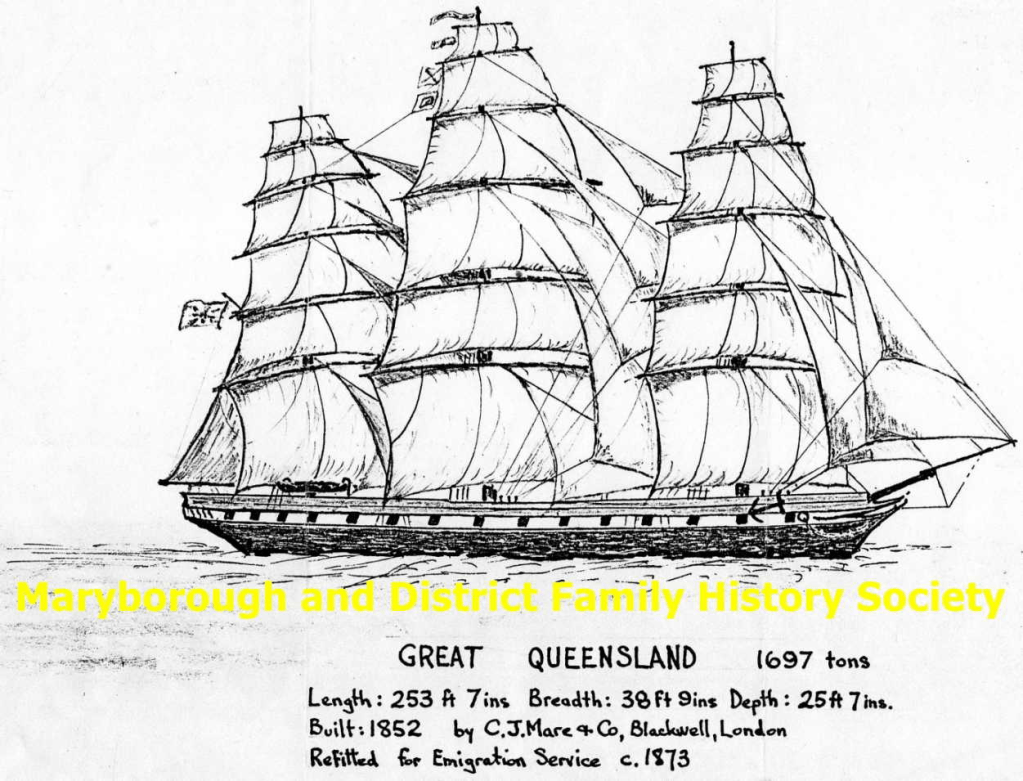

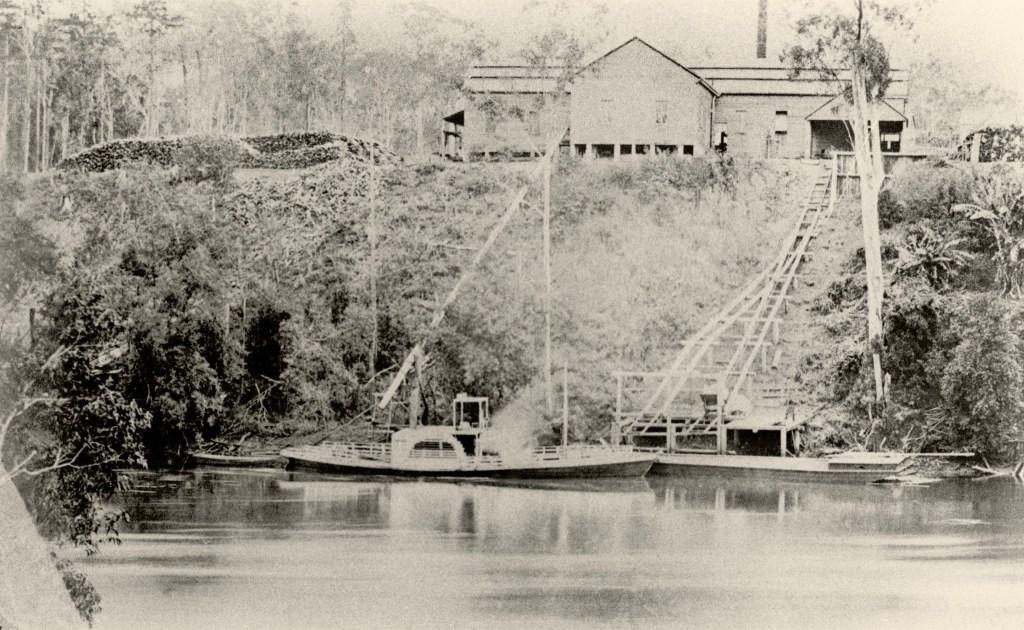

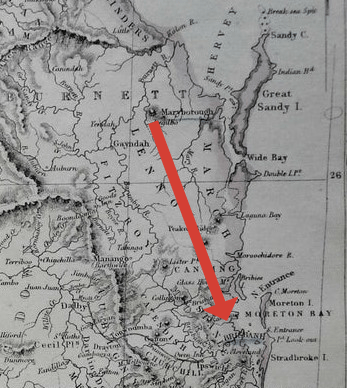

My great-grandfather, Peter Bermingham, arrived in Maryborough, Queensland, on October 9, 1874, as a free settler aboard the ship Great Queensland, which departed from London.

Upon his arrival in 1874 in the relatively new colony of Queensland—established in 1859—Peter Bermingham would have found abundant opportunities for work in farming or in various trades such as blacksmithing, carpentry, and sawmilling. Land clearing, timber-getting, and sugarcane farming formed the backbone of the local economy.

Apart from basic horse-drawn ploughs, nearly all farm work relied on gruelling manual labour. Sawmilling was an extremely dangerous occupation, with steam-powered saws and belt-driven machinery operating without safety guards. Deaths and serious injuries were common. Working hours were long, and life was physically demanding. Medical care was limited, and epidemics such as influenza, typhoid, and measles posed constant threats. Poor sanitation often led to outbreaks of disease.

For a young Irish immigrant like Peter, life in Maryborough offered hope—certainly far more than famine-ravaged Ireland—but survival demanded resilience and relentless hard work.

Being a single man allowed Peter the freedom to move wherever he could find suitable work, primarily as a farm labourer. After arriving from Ireland & spending some time in the Maryborough region, he appears to have gradually made his way south to the Pine Rivers area, on Brisbane’s northern outskirts. In late 1875, he found employment on Ellen Dunn’s farm, working as a labourer after the death of her husband, John.

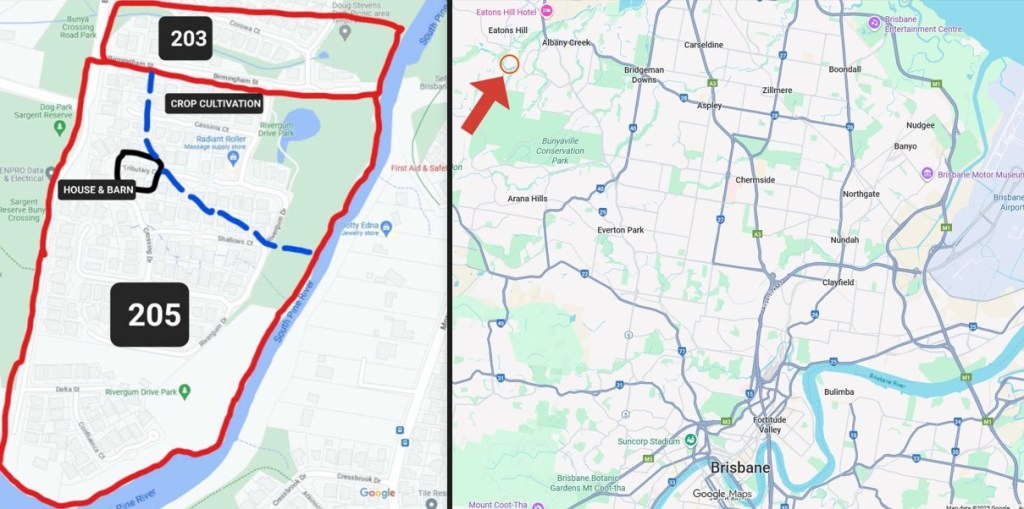

My great-grandmother Ellen’s farm was situated on a bend of the South Pine River, on the northern outskirts of Brisbane, where the modern-day suburb of Eatons Hill now stands.

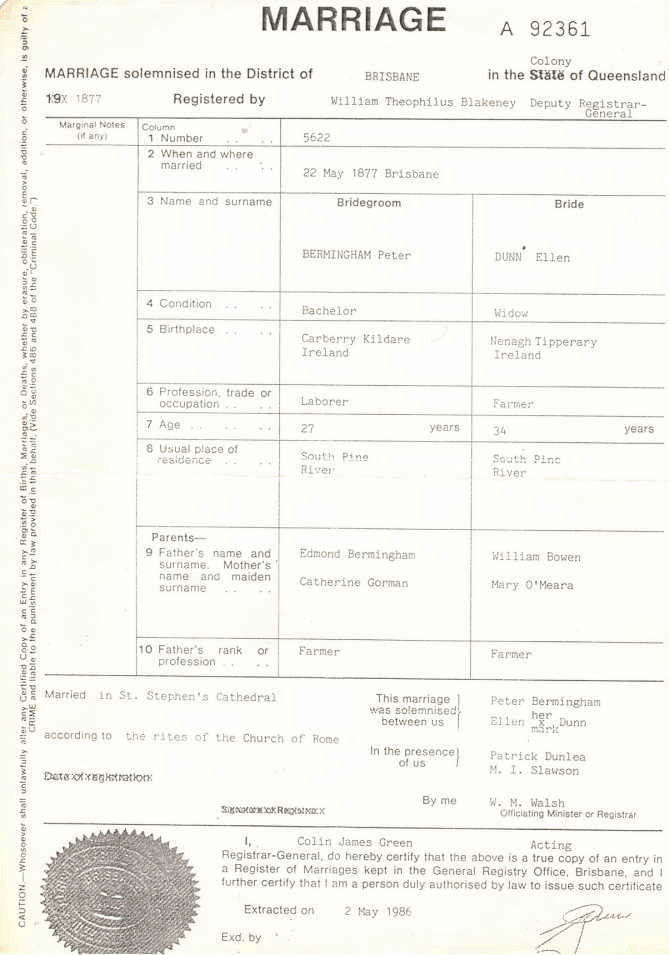

Things must have worked out fairly well between Peter and his employer, because on 22nd May 1877 at age 27 (showing on his wedding certificate), he married the widow Ellen Dunn (aged 34), at St Stephens Cathedral in Brisbane. Ellen already had six children from her first husband, though one had died in infancy. I’ve done a separate story on Ellen’s life, which can be viewed here https://porsche91722.com/2023/03/04/ellen-bermingham-dunn-bowen/

The ages on his birth record & marriage certificate align.

After their marriage, Peter and Ellen settled back to life on the farm at Pine Rivers, north of Brisbane. Peter’s occupation was recorded as labourer, while Ellen was listed as a farmer; both were of the Roman Catholic faith. They welcomed one child, Edward, who was born almost exactly nine months later, on 17 January 1878.

Beyond these few details, Peter’s life in Queensland remains elusive. I have found no trace of him in official records such as the Queensland electoral rolls, citizenship documents, death certificates, or burial records. The only reference comes from a newspaper notice reporting Ellen’s passing in 1915, which mentions that Peter had died approximately seven years earlier, approximately 1908.

The only official records I have for him are his arrival in Queensland, the marriage certificate, and a few references to his time at Pine Rivers on the farm. Ellen appears on the 1905 Moreton electoral roll as living at South Pine River, listed under “domestic duties.” There are no existing records for Peter, which could indicate that their relationship had broken down by that time, or perhaps that he lacked citizenship, voting rights, or had simply disappeared.

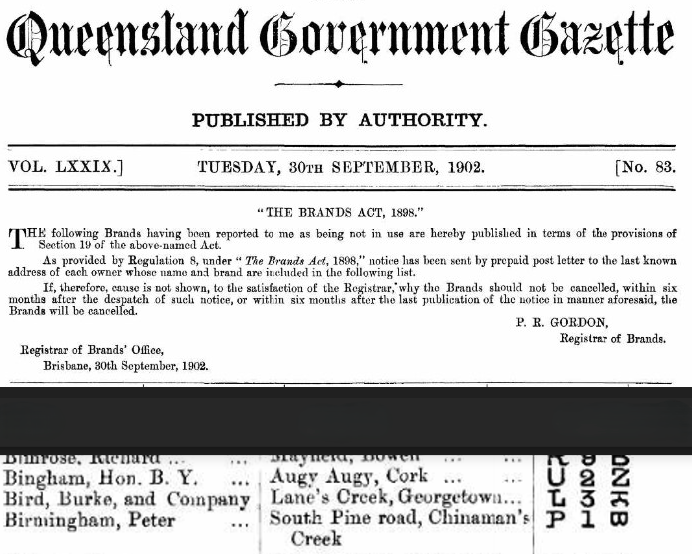

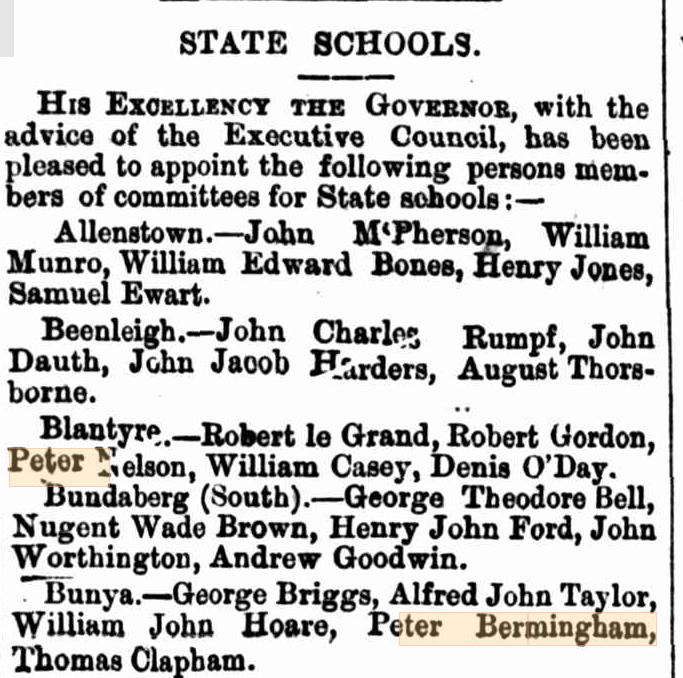

Ellen obviously still had close contact with her children from the Dunn side of the family. Her son from her previous marriage to John Dunn (who had died in 1875), John Dunn Jnr was a police officer. It is a possibility that Peter may have had a checkered past and associated with some people who were known to the authorities. The Dunn’s may have been protecting their mother by pushing Peter out of the family circle. It happens in a lot of cases where the mother remarries shortly after the death of her husband, and the children for one reason or another, take an instant dislike of the new guy. All of this is supposition on my part, but I believe that it may have been the case here. Edward wasn’t particularly close to his father and kept in closer contact with his mother and his Dunn siblings as he got older. There are many inconsistencies & gaps in Peter’s life that don’t add up. I found this newspaper article from the Brisbane Telegraph of 11th March 1878. This is around the time that Peter & Ellens’s son, Edward was born – 17 January 1878. Bunya State School was approximately 2 km from Ellen’s farm. The Dunn kids would have gone to this school. These committees were the forerunners of modern-day School P & C Associations. Peter had been making an attempt to be part of the family, by being involved with the kids & helping out at their local school.

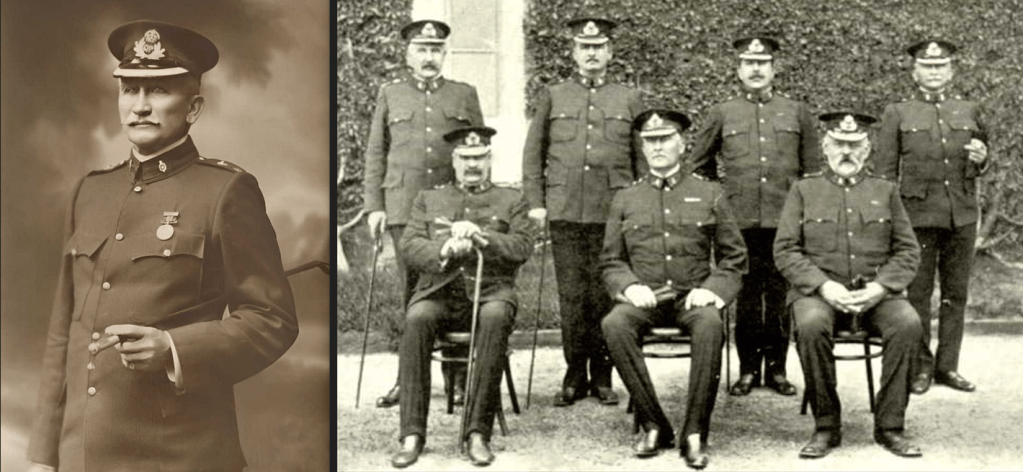

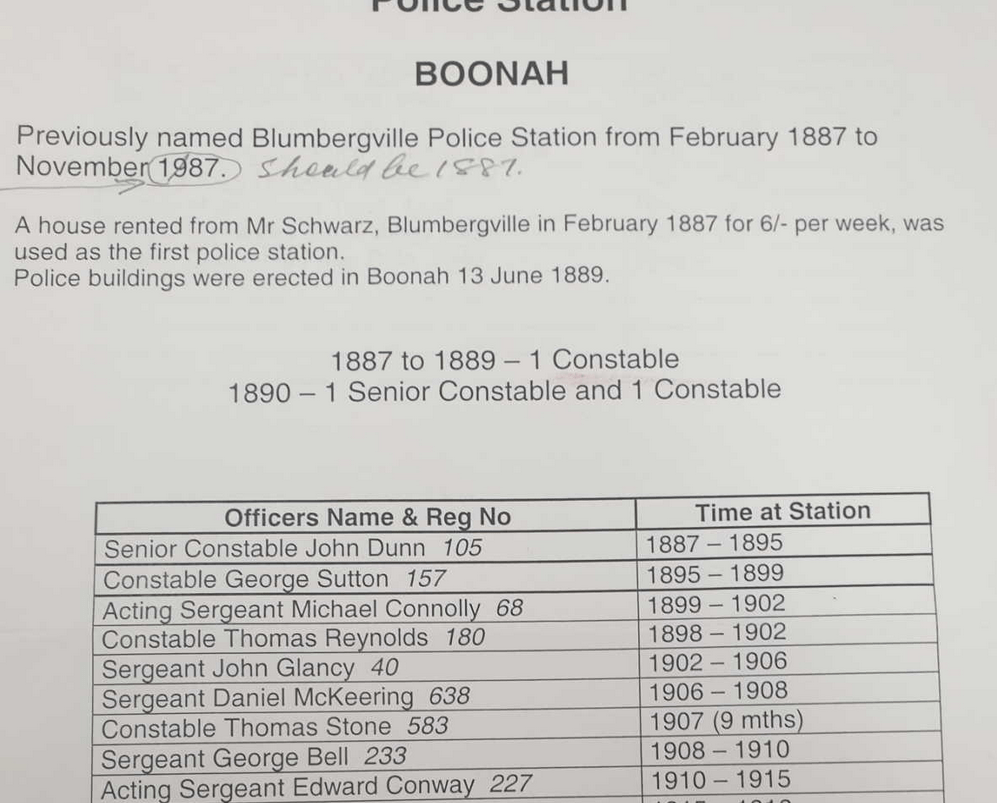

Senior Constable John Dunn Jnr was assigned to be the first police officer stationed in Boonah in 1887. Edward followed his half-brother to Boonah shortly afterwards in early 1888.

As I have already stated, I have the impression that Peter may have had a few skeletons in the closet. As far as I know, he doesn’t appear to have ever gone to live at Boonah, & lived most of his life after arriving in Australia, in the Pine Rivers area, just north of Brisbane. Peter died in approximately 1908 at age 58 or thereabouts. Cause unknown, date unknown, place unknown. There’s a whole number of potential options that are up for debate, as to why Peter’s historic movements cannot be verified. Unusually, there’s no record of a death certificate, taking into consideration, that even by 1908 standards, more records were then being kept of the population, with Queensland becoming a state in 1859, and Australia becoming a nation in 1901. There are no media reports in the newspapers of the day, of criminal activity or foul play. He may have travelled down south or even left the country completely. Somehow though, word must have gotten through to Ellen of his passing. There’s no cemetery headstone. Back in those days, the Catholics were all buried, so again, slightly unusual that there was no funeral service or burial recorded. In 1915, when Ellen died, she was buried at Lutwyche cemetery in Brisbane (under the name of Ellen Bermingham) near to her first husband, John Dunn Snr. Due to not having any accurate records, most of the story of Peter’s life is all hypothesis. I have attempted to track his life, with the limited information that I have been able to obtain. The man may have been completely legitimate, but even taking into account that the records of the day were fairly sparse, it is somewhat odd that he doesn’t show up anywhere. As I mentioned at the beginning, ancestry tracking is all about joining the dots. Unfortunately, there are not too many of Peter’s dots to join.

There is always a risk of portraying people as indifferent or neglectful simply because of a lack of records or information. I certainly don’t want to do that here, given the limited documentation of Peter Bermingham’s life. His story remains a work in progress—one that will need to be revised as more factual records and information come to light.

Aside from the brief mention of his death eight years earlier in Ellen’s 1915 obituary, my great-grandfather, Peter Bermingham, seems to have vanished without a trace.

Edward Bermingham was born on the 17th January 1878, to parents Peter & Ellen Bermingham (Dunn/Bowen), who lived at South Pine, where the current day suburb of Eatons Hill now exists on the northern outskirts of Brisbane, Queensland. Ellen was widowed from her first husband John Dunn, at the time of her marriage to Peter Bermingham.

Young Ned spent his early years on the farm at South Pine and received his first education at the nearby Bunya Primary School.

Ned Bermingham, at the age of 9, left South Pine and moved to Boonah in 1887. His half-brother, John Dunn Jnr (from Ellen’s first marriage to John Dunn Snr, 1832-1875), was appointed to be the first policeman stationed at Boonah. John Bowen Dunn served as the police officer at Boonah until 1895.

As to why young Ned left the family farm at South Pine River at such a young age, I can only speculate. My best guess is that, being considerably younger than his half-siblings—the other Dunn children, who had probably taken over the running of the South Pine property by then—Ellen sent him to Boonah to live with her eldest son, John Dunn Jnr. Perhaps she hoped John would take Ned under his wing and guide him toward further education or a possible career path.

Although Peter Bermingham was still present at South Pine, he appears to have had little or no influence on his son Ned’s future. John and Martha Dunn never had children of their own. Of all Ned’s parents and siblings, it was his half-brother, Constable John Bowen Dunn, with whom he developed the strongest lifelong bond. I believe my own father was named John as a mark of respect for the deep admiration Ned held for his older brother.

Constable John Bowen Dunn, who was 18 years older than Ned, became more of a father figure to him than his biological father, Peter Bermingham. John Dunn played a major role in Ned’s upbringing, particularly during his teenage years in Boonah. Our family still holds memorabilia—including service medals—from Sub-Inspector (3rd Class) John Bowen Dunn’s distinguished police career that were passed down to Ned.

Reflecting on my own childhood, I cannot recall ever hearing my great-grandfather Peter Bermingham’s name mentioned. I didn’t even know of his existance until my later interest in family history began.

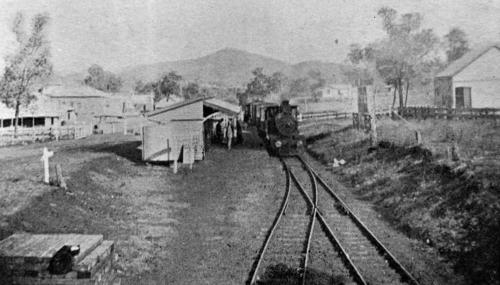

The railway line to Boonah and on to Dugandan, was opened in 1887, so both Senior Constable John Dunn & young Ned Bermingham would have travelled to Boonah on the newly opened rail link, which also coincided with the opening of the new Boonah Police station.

Ned Bermingham attended school in Boonah & would have completed his primary education at the age of 12, which was fairly common for that era of education in Queensland. Young men in the country regions typically worked on their families’ farms or businesses, pursued higher education, or learned a trade.

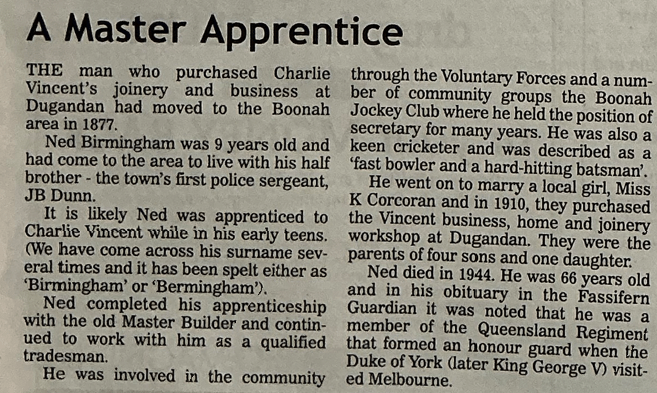

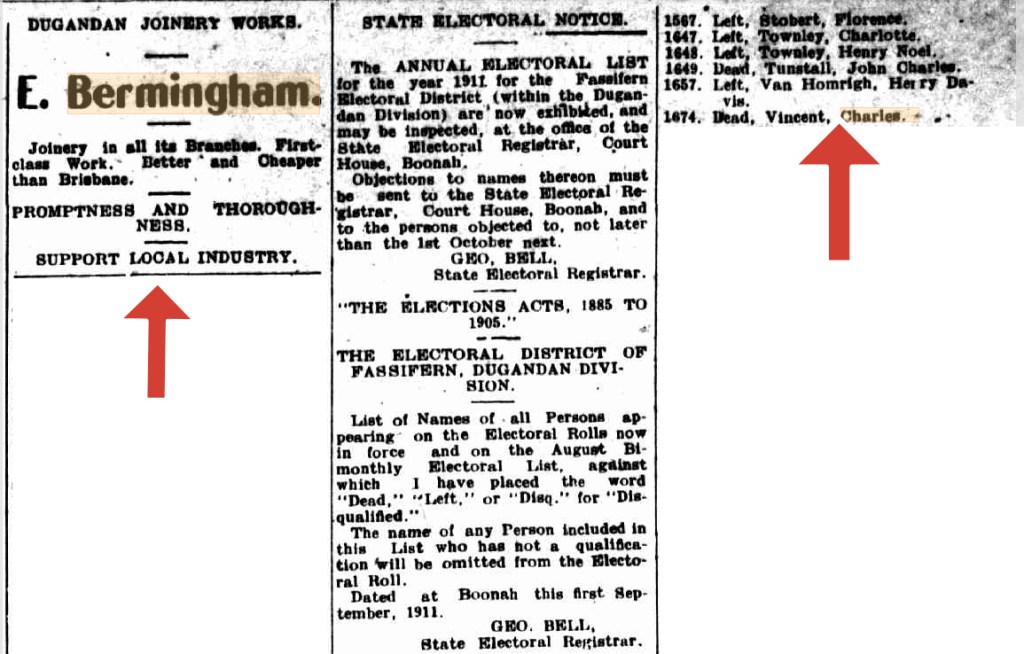

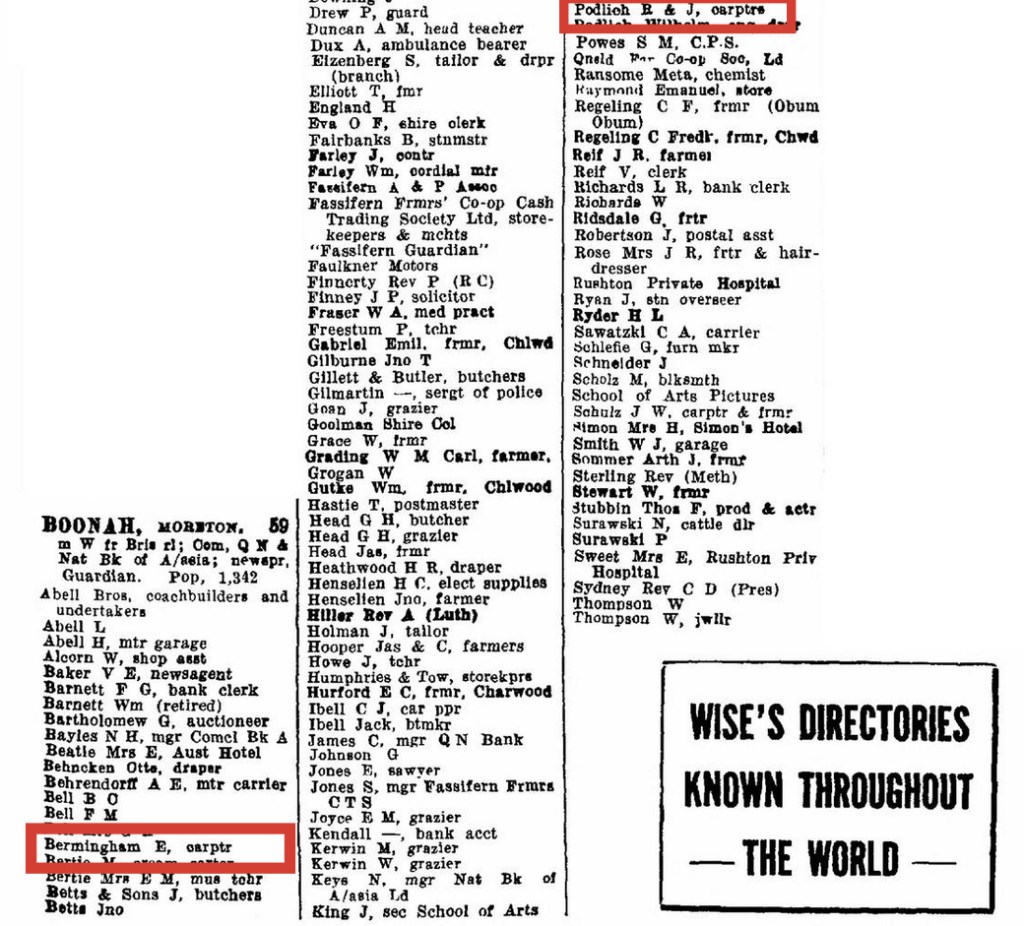

After completing his schooling in Boonah in the early 1890s, Ned received assistance from Senior Constable John Dunn, who helped him secure an apprenticeship in cabinetmaking and carpentry. Dunn arranged for him to train under local master builder Charlie Vincent, owner of the Dugandan Joinery Works.

Records indicate that Vincent constructed numerous residences and contributed to various projects and renovations across the district, including Simon’s Hotel in Boonah and Badke’s Hotel in Roadvale. He was particularly renowned for his ecclesiastical joinery, completing work for several churches in the district—Christ Church Boonah, the Boonah and Kalbar Catholic Churches, the Dugandan Lutheran Church, and the new Catholic Church at Croftby.

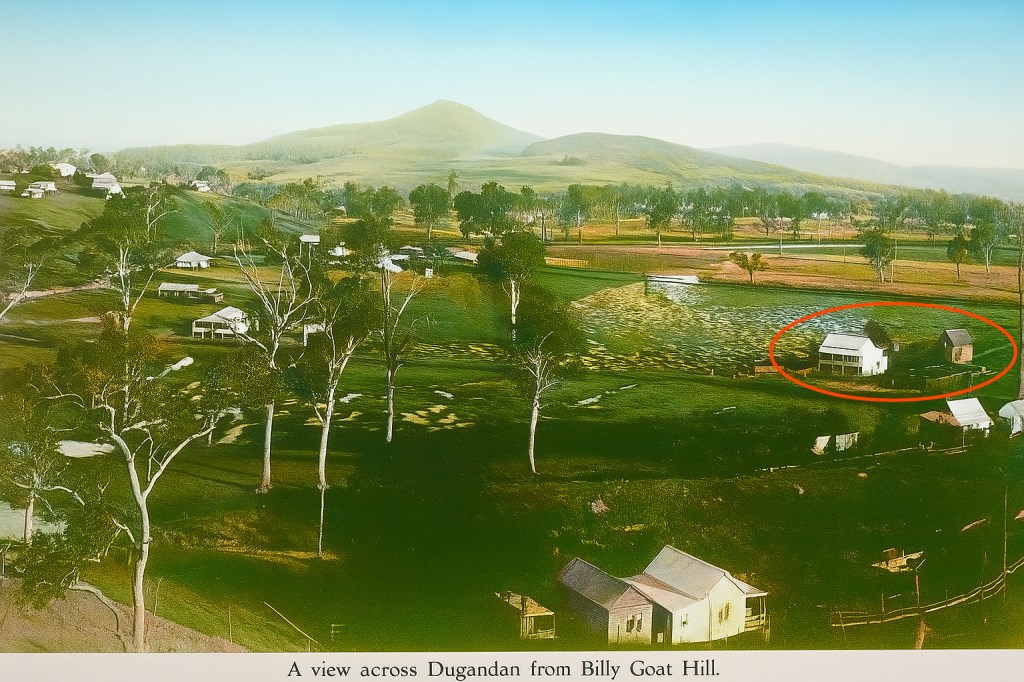

Under Charles Vincent’s guidance, Ned completed his carpentry apprenticeship and refined his craftsmanship while working on various projects throughout Boonah and the Fassifern Valley. In early 1910, Ned purchased the business, Dugandan Joinery Works, along with the house & workshop following Vincent’s death. Having worked closely with the master tradesman for many years, Ned was well prepared to uphold the business’s strong reputation for quality workmanship.

By September 1910, Ned was placing advertisements in the local newspaper—the Fassifern Guardian—as the proprietor of the Dugandan Joinery Works, marking the formal transition of ownership. This change ensured the continuity of skilled joinery in the district, with Ned maintaining the enterprise that had long served the Boonah and Dugandan communities. By this time, he had become a respected and well-established member of the Boonah community.

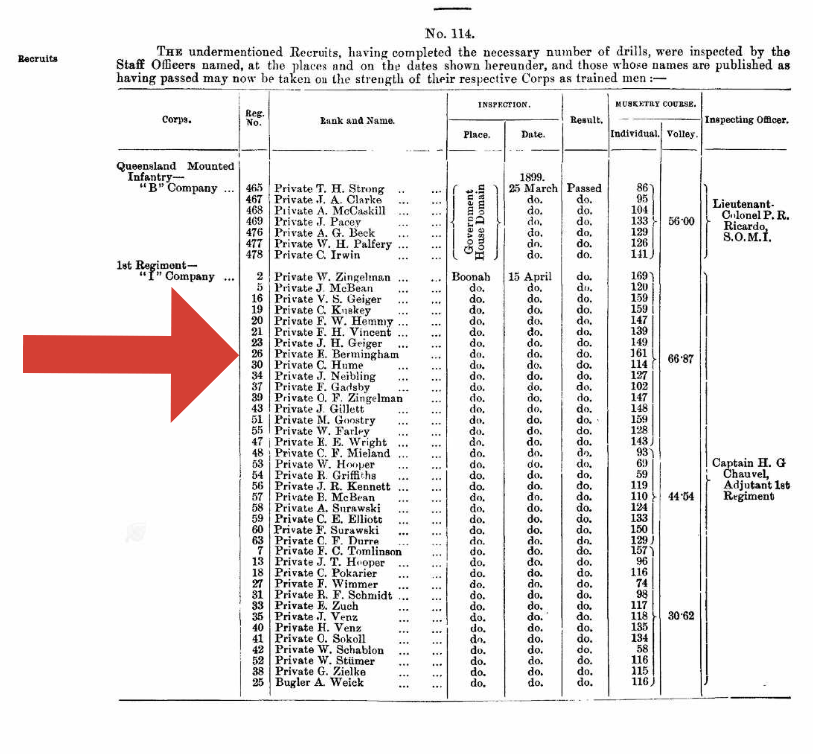

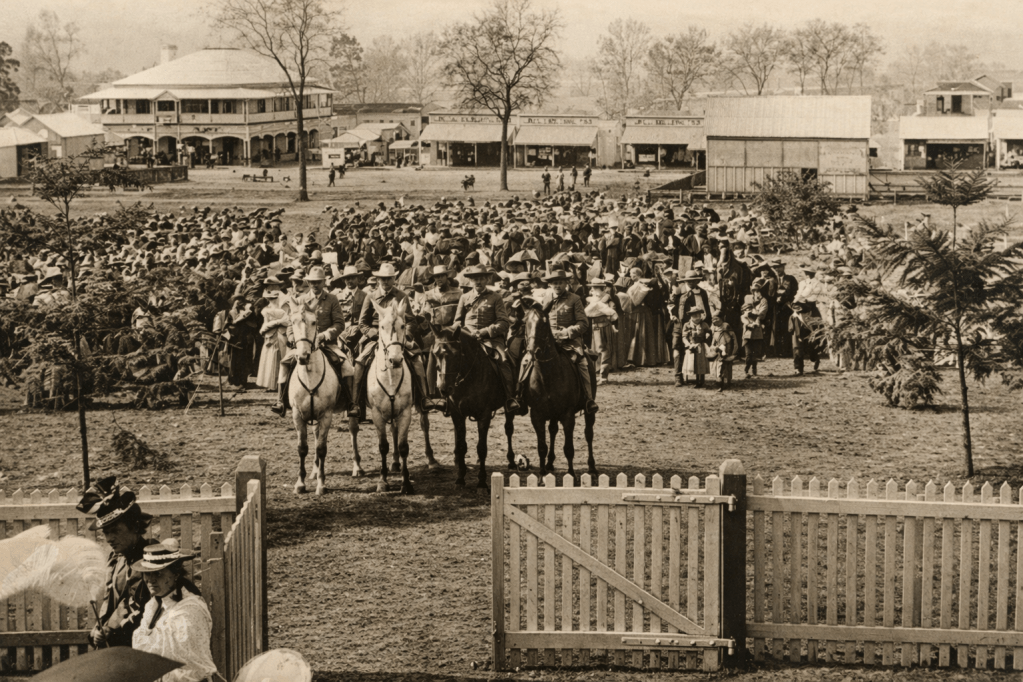

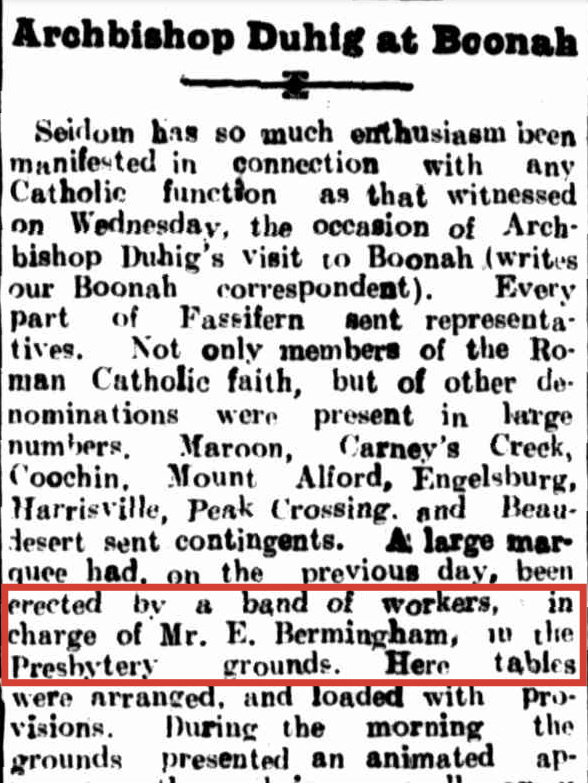

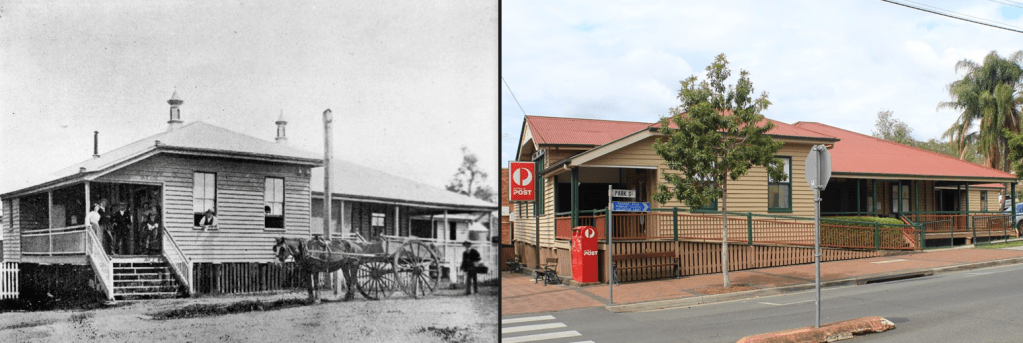

Ned was a deeply community-minded man. In 1899, he had completed the required number of drills to join the West Moreton Volunteer Regiment, based in Boonah. Throughout his life, he was an enthusiastic sportsman, taking part in cricket, shooting, and horse racing. He also contributed to the upkeep and running of the Catholic Church & grounds in Boonah.

Life in small country towns during the early twentieth century encouraged strong community involvement. In those days—long before the advent of electronic or digital devices such as television or the internet—people were more engaged with one another and deeply involved in local pastimes.

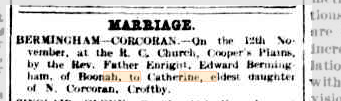

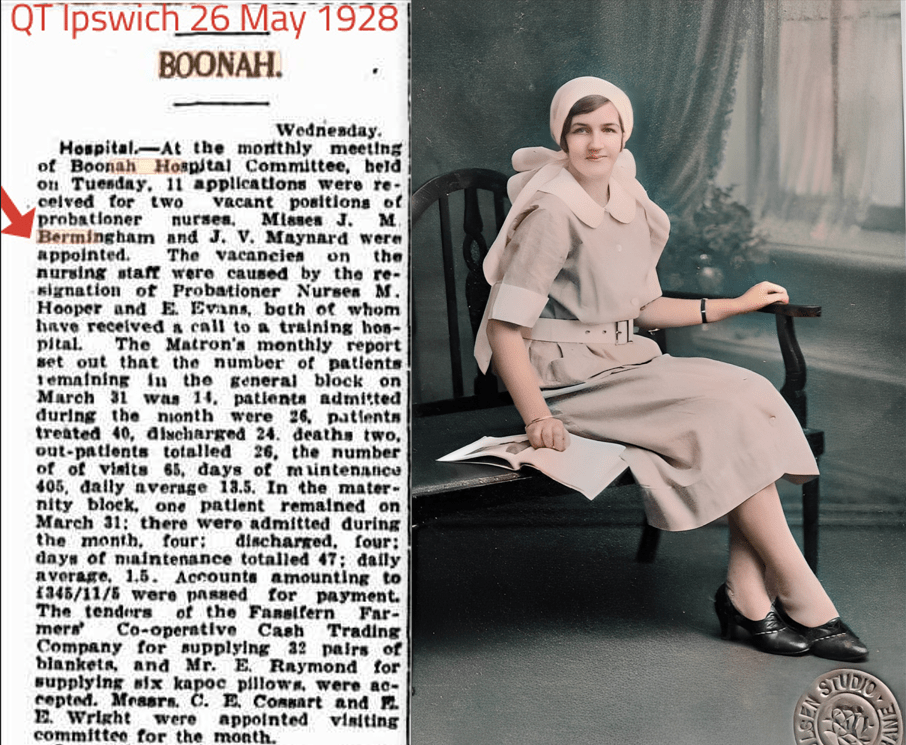

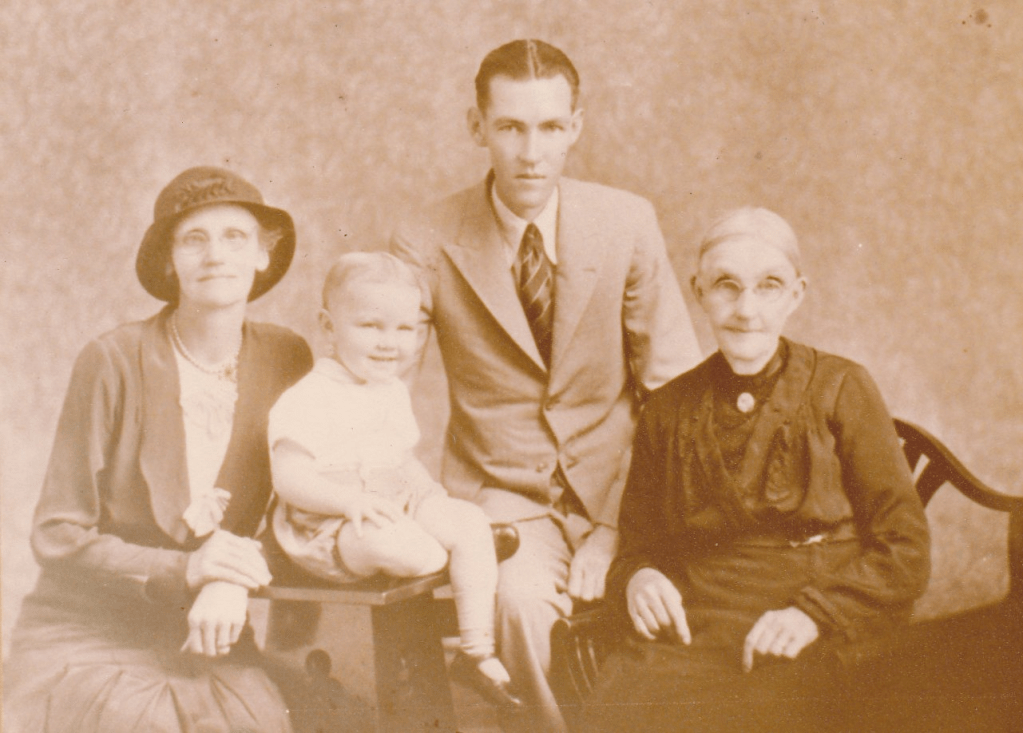

Edward Bermingham married Catherine Mary Corcoran on November 12, 1903, at the Catholic Church in Coopers Plains, on the southern outskirts of Brisbane. Their first child, Edward Joseph Bermingham, was born on June 24, 1904. The reason the wedding took place nearly 100 kilometers from the Fassifern Valley was likely because Catherine was in the early stages of pregnancy. At the time, the region—particularly the Catholic community in Boonah and the Fassifern Valley—was deeply conservative. To avoid local scrutiny and judgment, the couple and their families likely chose to marry away from the disapproving eyes of their home parish.

It may seem absurd to imagine today that such a decision was necessary, but social attitudes and moral expectations at the time were far more conservative than those of the modern era.

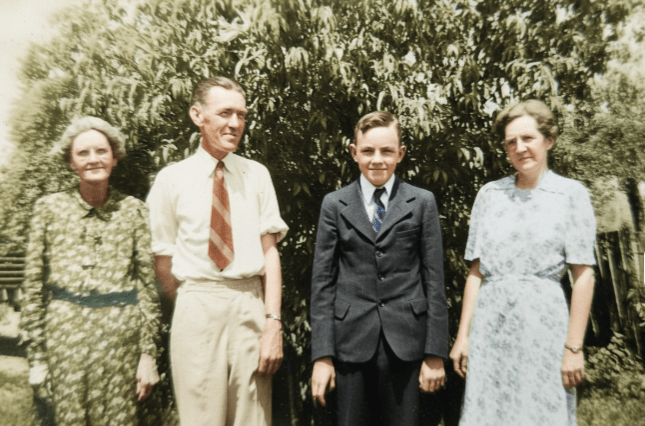

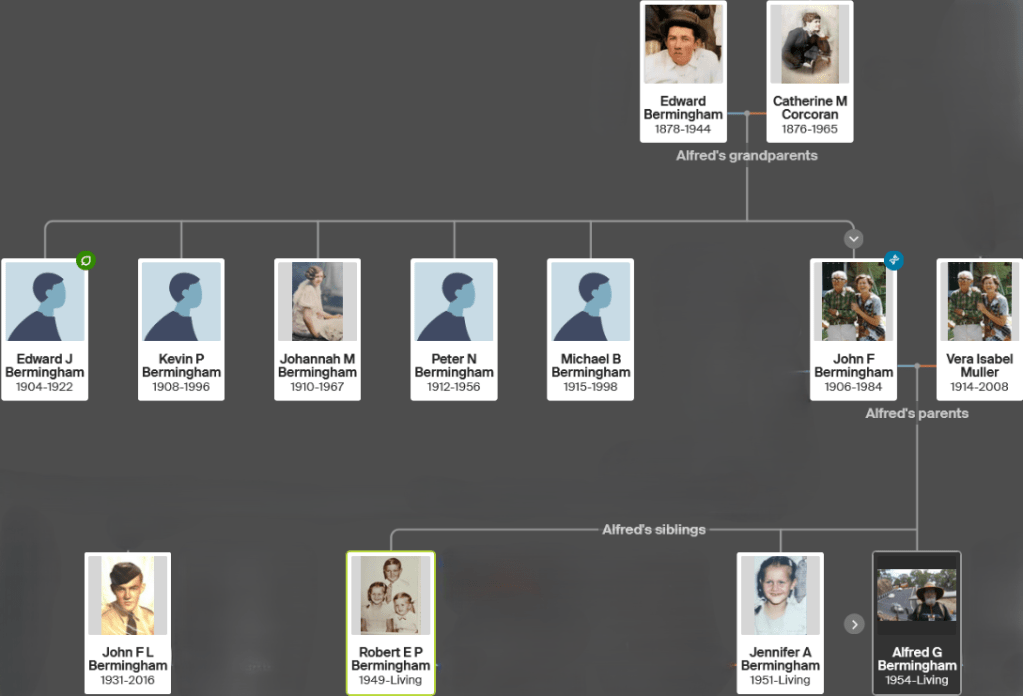

Ned Bermingham worked as a carpenter and cabinet maker throughout his entire adult life in the Fassifern Valley district. He and Catherine had six children, one of whom was my father, John Francis Bermingham.

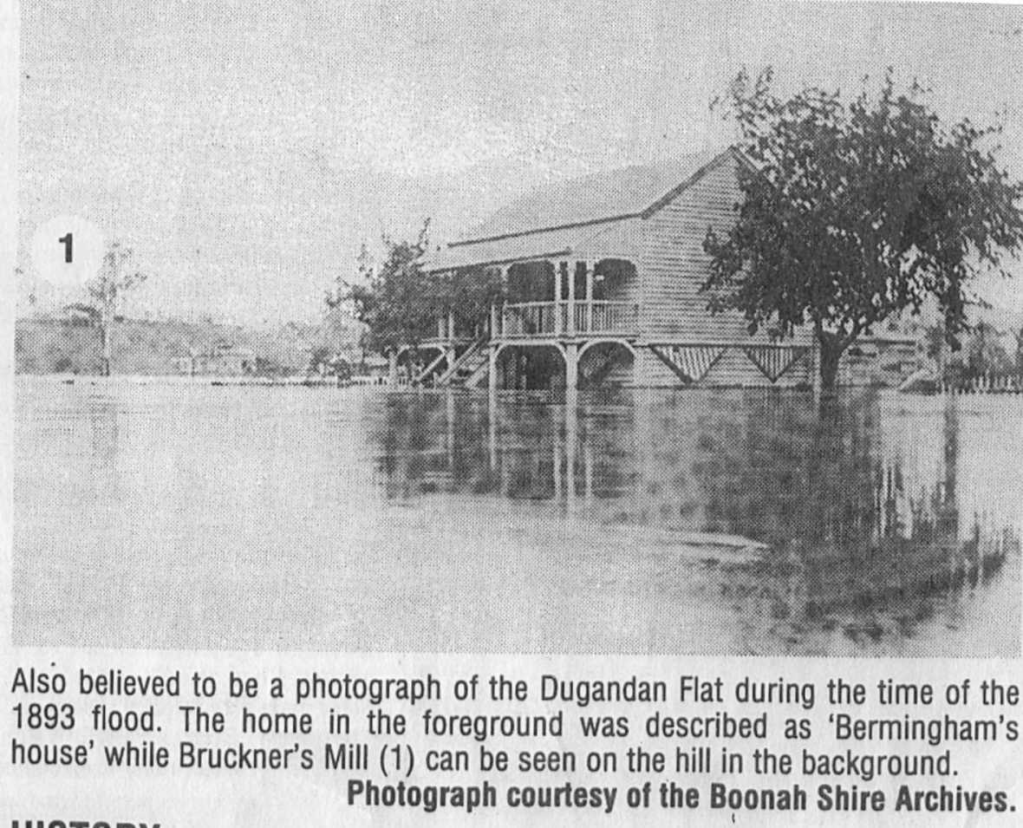

By 1910, when Ned took over the Dugandan Joinery Works from Charles Vincent, he and Kate, had recently welcomed their fourth of six children, Johanna Mary (Molly) Bermingham—their only daughter. According to historical records, the house in Dugandan, built c1892 by Charles Vincent, on part of land portion 31, was a two-storey residence situated on 2.5 acres of land. The ground floor featured a lounge, dining room, kitchen, laundry, storage area, and billiard room. The upper level included another kitchen, dining room, lounge or hallway, two double bedrooms, and a verandah.

The roof was originally made of cedar shingles later overlaid with galvanized iron. The lower level was equipped with acetylene lighting. Behind the house, Charles had also constructed a two-storey workshop with a shingled roof and unlined interior. The upper floor served as a carpentry space, while the ground level housed a fully equipped wood-machining shop fitted with lathes, a guillotine, circular, band, and jigsaws, as well as a steam engine, pulleys, and drive shafts for full operation.

In an interesting twist, I managed to uncover a newspaper advertisement placed by Ned in a Brisbane newspaper in 1912, offering the business for sale—just two years after he had taken it over from Charles Vincent in 1910. Could Ned have been getting cold feet about running the enterprise, especially following Vincent’s successful management of the joinery works he had established? It’s possible that Ned found himself in debt after purchasing the business and was testing the market in case he feared financial difficulties ahead. It is also notable that he chose to advertise the sale in the Brisbane press rather than in the local Boonah or Ipswich papers. In any case, the sale never went ahead.

Both Ned Bermingham and Rudolph Podlich were employed by Charles Vincent as carpenters in the early 1900s. By the time Simons Hotel was completed in 1902, Ned had finished his apprenticeship. Ned and Rudi Podlich were likely close friends, having completed their carpentry apprenticeships under Vincent’s guidance. After Ned’s death in 1944, the Podlich and Bermingham families lived next door to each other on Macquarie Street, Boonah.

As a young child visiting Boonah with my parents in the 1960s, I often met the Podlich family. Little did I know then that Rudi—who was still alive at the time (he died aged 93 in 1986)—had completed his apprenticeship alongside Ned under Charles Vincent’s supervision, all those years earlier.

As a child, I remember many old pieces of furniture and cabinets in my grandmother’s Boonah home. At the time, the quality of my grandparents’ furniture wasn’t something I paid much attention to. However, in retrospect, their precision and handcrafted detail suggest they were likely made by Ned himself. Being a skilled cabinetmaker, it’s unlikely he would have purchased mass-produced furniture.

C Vincent – Dugandan Joinery had disappeared from the almanacs by that stage.

The photograph below shows the family home around the time of the 1893 flood, well before Ned purchased the house and business from Charlie Vincent, when Teviot Brook had broken its banks.

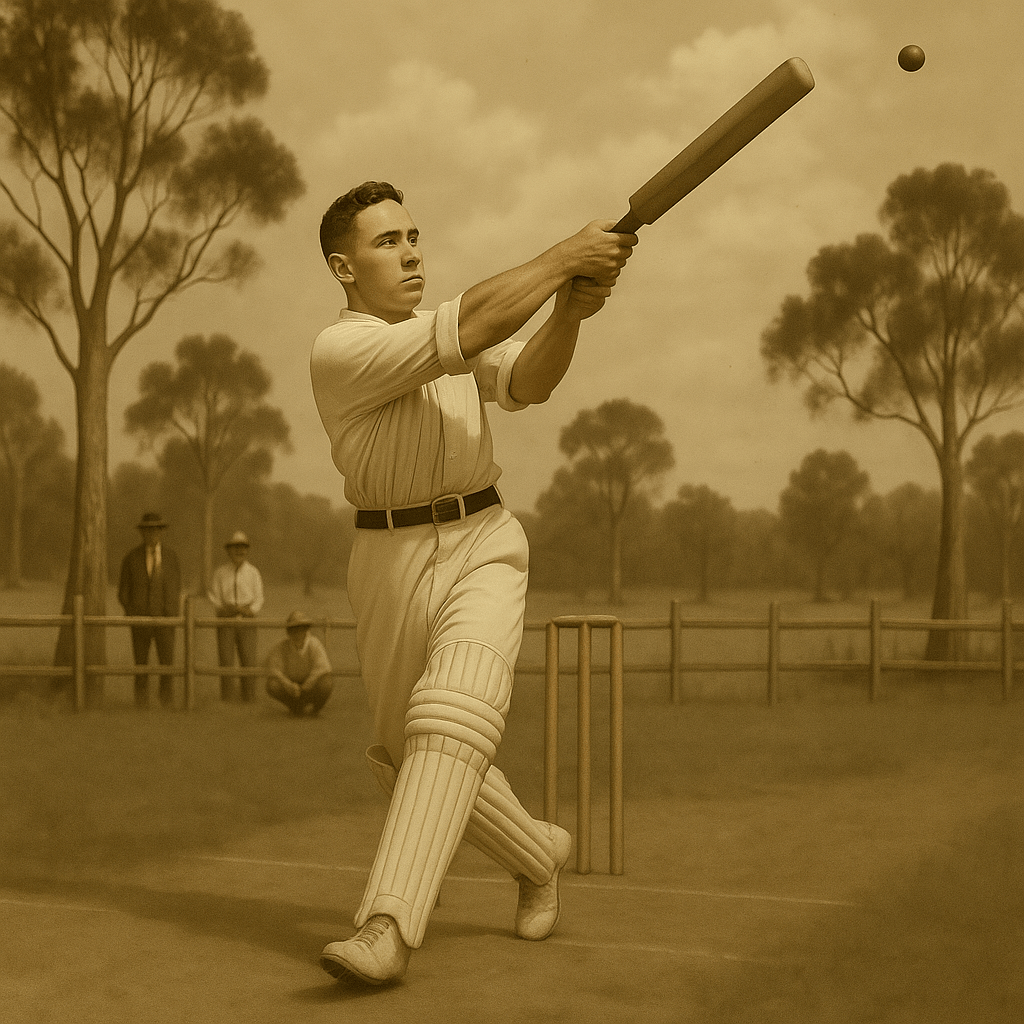

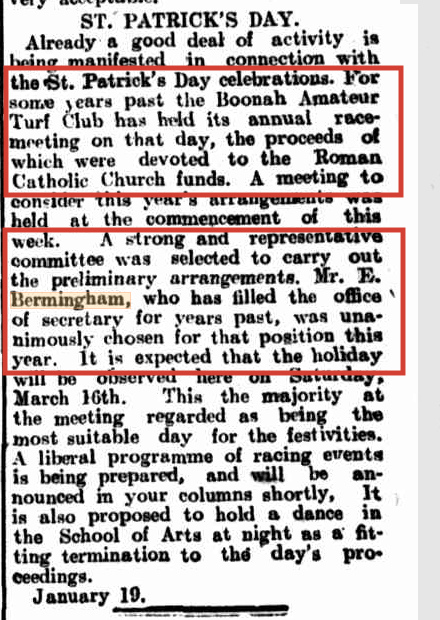

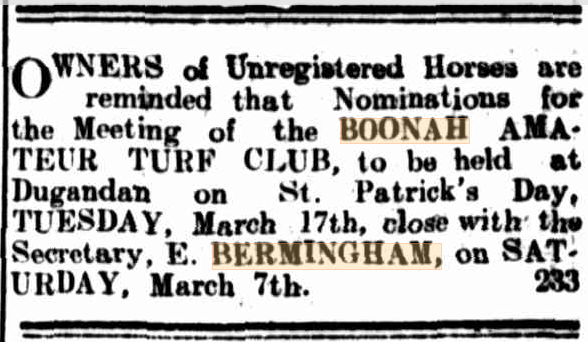

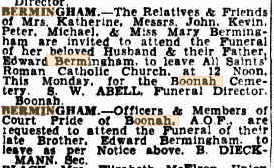

Ned was deeply involved in local sport, playing cricket for Boonah in the Fassifern Valley competition, and was also an avid horse racing enthusiast. He served as secretary of the Boonah Amateur Turf Club for many years. In addition, he was an accomplished marksman and was also a member of the Ancient Order of Foresters, Boonah Court, a lodge & benevolent society originally established for men working in industries connected to timber and forestry.

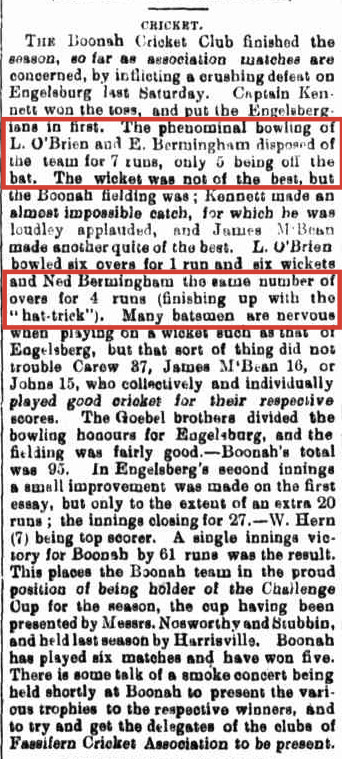

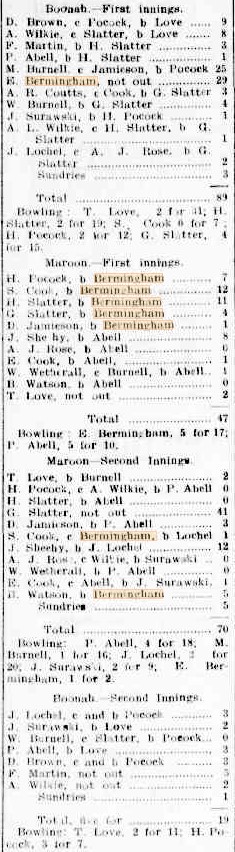

Ned was partial to playing social cricket, too, in fact, any sort of cricket. He loved the game. The above sports item was from the Queensland Times 18 Oct 1902. T20 cricket didn’t exist back then, but Ned’s hard-hitting slogging agricultural style of batting would have seen him excel as a limited-overs cricketer these days. I think the fact that it was a social game was lost on the journalist.

Ned topped the bowling averages for his team. Pity they couldn’t spell his name correctly.

There’s no evidence to show that Ned had a very close relationship with his father – Peter Bermingham, who was still living north of Brisbane, around the Pine Rivers area, in the early 1900s. He appears to have leaned more toward his mother and the Dunn side of the family (his half-siblings) to remain in contact with.

Ned was a religious man, having been born into the faith by his Irish Catholic parents. However, I get the distinct impression that he wasn’t as quite a strictly observant Catholic as his wife, Catherine. It’s worth remembering that during that period in Australia’s history, society was deeply conservative. People, especially those in smaller rural towns, generally held strong religious convictions.

Many early settlers had come to Australia from countries where religious persecution was common. As a result, a kind of reverse persecution emerged—an unspoken expectation that everyone attended church, regardless of denomination. Australia was self-promoted as a beacon of religious freedom as long as you were a Christian. People were free to worship within any Christian faith they chose, yet social convention dictated that everyone was expected to take part.

This context may help explain why Ned was involved in so many community activities around Boonah, such as cricket, horse racing, shooting, and his local lodge. Based on his interests, it’s fair to assume he was a sociable man who enjoyed spending time with others—and probably shared more than a few cold beers with his mates.

Ned’s degree of religious faith may not be in question, however I think he may have been more of a “social” member than a staunch God bothering member of the local RC congregation.

Ned’s active involvement with local sporting pursuits also had him being the secretary of the Boonah Amateur Turf Club for many years. I’m sure there was no conflict of interests with the proceeds of the race meeting being donated to the local Catholic Church.😃

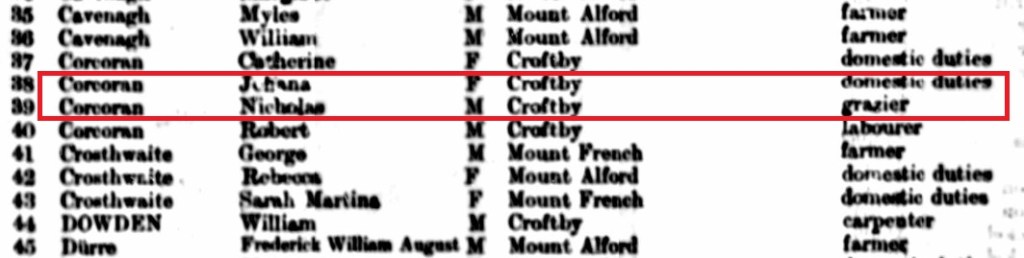

Catherine’s upbringing was from a very devout Catholic family and she carried those strong beliefs throughout her entire life. Catherine Mary Corcoran was born 20th November 1876 at Fassifern Valley Queensland. As previously mentioned, Catherine or Kate as she was known, & husband Edward (Ned) had six children. Edward Joseph (1904-1922), John Francis (1906-1984), Kevin Patrick (1908-1996), Johanna Mary (1910-1967), Peter Nicholas (1912-1956), Michael Bowen (1915-1998).

She passed away in 1965 at the age of 88. I can still remember the local Catholic priest visiting her home to conduct a full Mass in Latin. As a child, it was honestly a little frightening to see him arrive in his black Valiant sedan, draped in rosary beads and religious regalia, before heading upstairs to perform his rituals. I remember sneaking down the hallway to catch a glimpse of what was happening.

He conducted an entire Mass in Latin with her, which was quite intense to witness. Their house was always dimly lit and filled with religious paintings and images of Jesus on the cross, along with scenes depicting God summoning souls to heaven and the devil dragging others down to hell, complete with fire and brimstone. It’s no wonder I turned away from religion early on after those experiences. A few years later, when I saw The Exorcist, all those memories came flooding back.

My Aunt Molly (Johannah Mary, Catherine’s only daughter) cared for Nana Bermingham (Kate) during her final years.

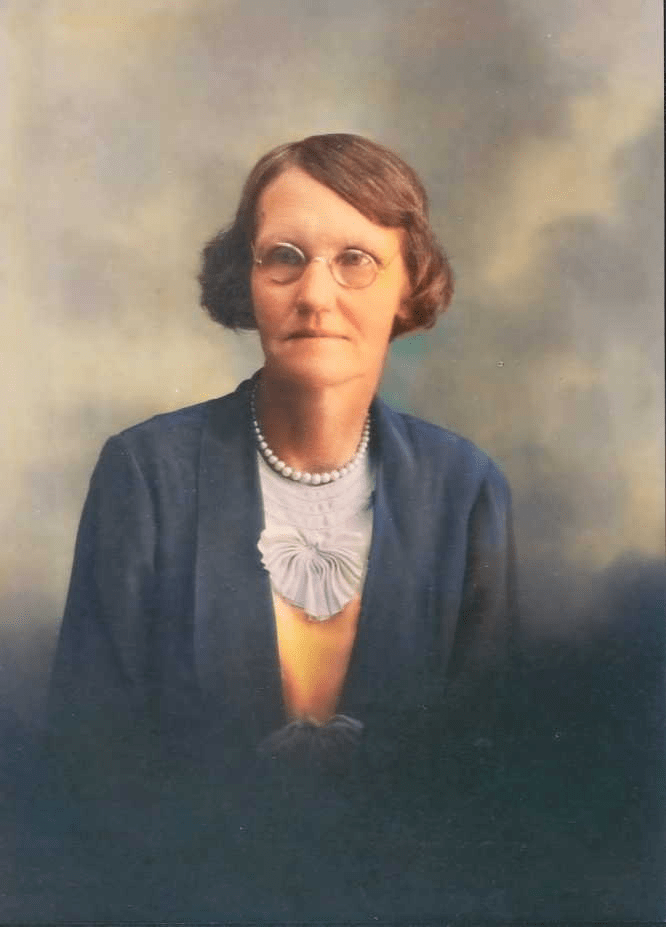

Aside from my father, Molly was the only other child in the family I came to know. She never married and spent her younger years working as a nurse at Boonah Hospital. The oldest brother, Edward Joseph died at 18 years old in an accident on the Corcoran farm. The other three brothers, Kevin, Peter & Michael, all had varying degrees of mental health issues & were eventually institutionalized. I’ve written a separate story on these guys, which can be viewed here https://porsche91722.com/2025/01/13/the-story-of-kevin-peter-michael-our-family-missing-persons/

By the late 1940s, Nana Catherine Bermingham, aged well into her seventies, required home care, and Molly had become her caregiver. She looked after her mother until Kate’s passing in 1965.

My memories of Molly are fond ones. She was a warm, homespun, and kind woman who always showed us care—especially me, as I was the youngest kid in our family. I truly liked Molly; she was a wonderful aunt.

Molly grew up as the only daughter of a carpenter tradesman, alongside her five brothers. As a child, she spent time on her grandparents Nicholas and Johanna Corcoran’s farm, where she learned to ride horses, care for animals, and repair things. At eighteen, in 1928, she pursued a career in nursing. Following Ned’s passing in 1944, she took on the responsibility of caring for her aging mother.

I always remember Molly as a woman who handled everything with determination & confidence. She chopped firewood for the wood stove, looked after the chooks, took care of general home maintenance—including doing her own carpentry, plumbing, mowing the yard, and repairing fences, killed the odd snake that made its way into their yard, and even slaughtered the rooster that had been fattened for the annual Christmas dinner at their place.

My grandmother, Nana Catherine Bermingham, was always kind to us grandkids. To be fair, none of them pushed the whole Catholic fanaticism on us. I think my dad, Jack, may have had something to do with that. My older brother, John Francis Leslie Bermingham, was the only child in our family who knew our grandfather, Ned. John was the only child from Dad’s first marriage. He was only about a year or two old when his parents separated. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that John had a turbulent childhood, but he did experience the instability of being shifted around among his dad, aunts, grandparents, and great-grandparents during his upbringing. Dad’s job as a telephone linesman kept him working away a lot during John’s formative years.

John was more knowledgeable about our grandparents, Ned and Kate Bermingham, than the rest of us kids. Consequently, he was better equipped to have an opinion or pass judgment on them. He mentioned to me several times his love and respect for his grandfather Ned, whom he regarded as a great man and his best mate while growing up in Boonah and the Fassifern Valley. Conversely, John didn’t hold the same feelings toward his grandmother, Catherine (Kate) Bermingham. In his words, “She was a woman who had a lot to put up with. As a religious bigot, she ruined the lives of Dad, Molly, and nearly me with her religious fanaticism.”

In John’s description of her “having a lot to put up with,” I suspect he was referring to Ned’s extracurricular interests—cricket, horse racing, shooting, and the lodge, among others. The couple lost a son, Edward, at just eighteen, and had three other sons—Kevin, Peter, and Michael—who suffered from mental disabilities. When Kate grew too old to care for them, the boys were eventually committed to an asylum.

As John put it, “Those boys were hard work.” It’s possible that Ned turned to his sporting activities as a way to escape the difficulties at home. Keep in mind that there was practically zero support for people with disabilities in those times. The situation was undoubtedly hard on Kate, who bore the burden of raising them largely on her own. Make of that what you will.

I can, to some extent, understand the anguish and suffering Kate must have endured. That said, there is no evidence to suggest the marriage was anything but normal, for the times—albeit perhaps slightly strained by Ned’s sporting activities outside the home, plus he was also running a business to support his family. In some ways, it’s not surprising that she turned to her faith and the church for comfort and support.

Years later, as I was growing up, I could see a woman nearing the end of her life. I was born in 1954, and she passed away in 1965, so during my childhood, I witnessed a woman utterly exhausted and perhaps ready to die. It seemed she had lost much of the vigor that once fueled her deep Catholic devotion. The spark remained, but in her declining years, I truly believe she no longer had the strength—or the will—to sustain it.

As an adult, I can look back & see why my Dad & his sister, my Aunt Molly, never mentioned anything about their Catholisism. I think they had well & truly gotten over it too.

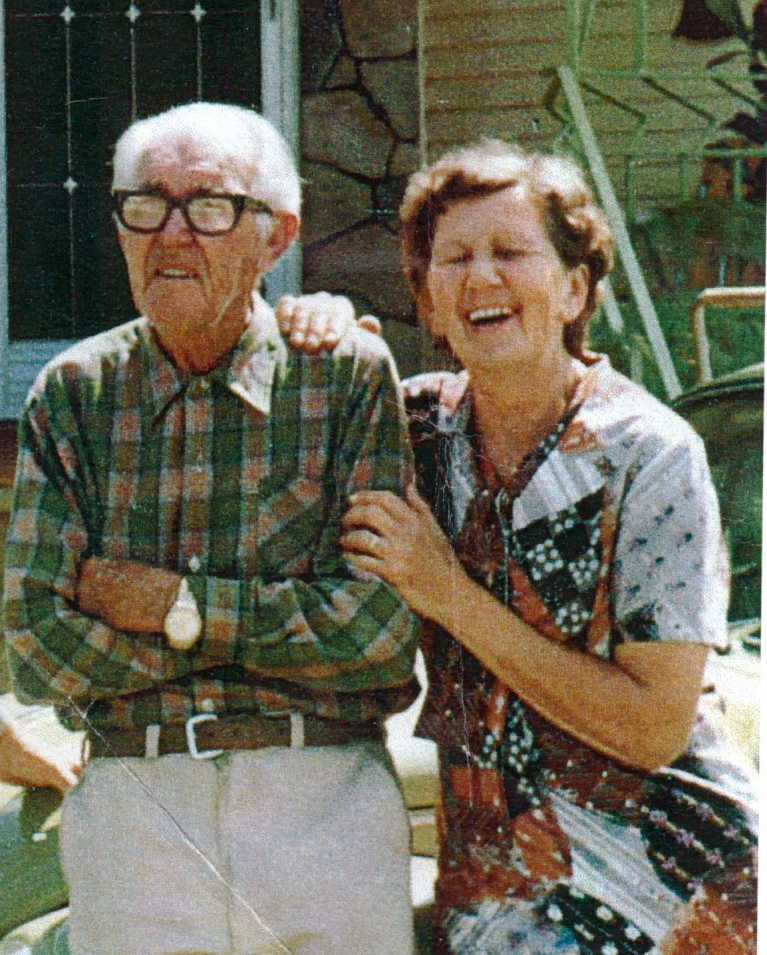

Ned died on 22 July 1944, aged sixty-six — long before I was born — from what appeared to be a stroke. Like everyone, he had his weaknesses and faults; none of us is perfect. He sounded like a good all-round bloke with a bit of a larrikin streak.

My brother John once told a story that, when Ned was having the attack, the family wanted to call a priest before calling the doctor or an ambulance. They were all devout Catholics, so that wouldn’t surprise me.

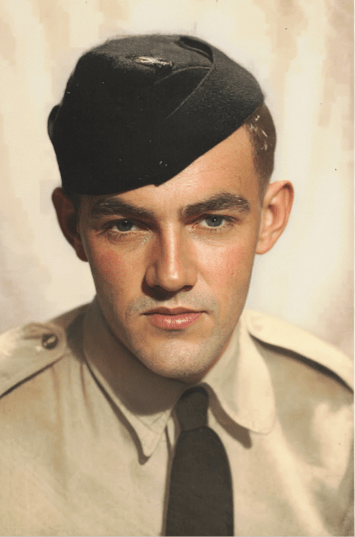

There’s no doubt that the death of his grandfather left a deep void in my brother John’s life. He was fifteen at the time, and they had been very close. Left with his grandmother — with whom he struggled due to her constant religious bigotry — John soon felt the need to escape. It’s little wonder he left Boonah to join the Air Force shortly afterward.

Around the early 1940s, Ned retired, sold the business and house in Dugandan, and built a new home on Macquarie Street in Boonah.

The above advertisement appeared in the Ipswich, Queensland Times in April 1945. I am not sure as to why the property was offered for auction in 1945, as Catherine Bermingham lived there until her death, twenty years later, in 1965, whereupon it was then auctioned off in a home & contents auction. I attended that auction as a kid with my Dad – John Francis Bermingham – Ned’s son.

As I’ve always believed, when compiling any ancestry story, it’s essential to tell the complete truth—warts and all—without omitting anything. Jumping to conclusions can be tempting, especially when face-to-face discussions with those involved are no longer possible. I’m also acutely aware that historical records may sometimes distort the facts.

My grandfather, Ned Bermingham, had a particularly compelling story. I believe he faced a few personal struggles throughout his life—challenges that most of us encounter from time to time. He appeared to be a laid-back, easygoing bloke who took life’s obstacles in his stride and enjoyed living to the fullest. Yet beneath that laid-back exterior, I suspect he grappled with the difficulties of raising three mentally impaired sons during a period when little help was available. His wife, Catherine, sought solace in her faith, which unfortunately led her to channel her frustrations toward other members of the family—her two other children, her husband, and her grandson.

As with Ned’s father, Peter Bermingham, there’s always a risk of judging people as indifferent or neglectful when viewed through a modern lens, without acknowledging the difficulties they themselves endured. Keeping the narrative truthful and balanced—highlighting both the admirable and the flawed aspects—is essential. To me, this is part of genuinely understanding and connecting with them, even long after they’re gone.

All that said, I believe Ned was a good father, a devoted family man, and a dependable provider. He may not have been perfect—but then again, who among us is?

When you strip Ned’s life back to the bare facts and records, he was simply an ordinary Aussie bloke — the son of farmers on Brisbane’s north side. He moved to the Fassifern Valley at nine years old with his older brother, learned a trade, worked hard all his life, raised a family, and faced many challenges with his sons, who had significant disabilities. Despite everything, he lived a normal, grounded life, much like the rest of us.

Yet his determination to become a talented sportsman, marry a local girl, raise a family, and ensure the success of his business, made him, in my view, something of a legend. Sometimes, we put overachievers on pedestals — but in Ned’s case, he simply worked hard throughout his life to get where he did. That, to me, makes him a true high achiever.

My grandfather, Ned Bermingham, along with my great-grandmother Ellen Bowen (Ned’s mother), see her story here https://porsche91722.com/2023/03/04/ellen-bermingham-dunn-bowen/ and my great-great-grandmother Catherine Ryan, see her story here https://porsche91722.com/2023/05/01/catherine-ryan/ are among the ancestors I would have dearly loved to meet. I’m sure they would have had some wonderful stories to share about their lives.

FULL DISCLOSURE – I have taken the liberty of including a few Artificial Intelligence enhanced images of Ned & Kate Bermingham in this story, at various points in their lives. At no stage can I suggest that these images are entirely accurate. The images were created with modern-day technology using the very few photos of the couple that were available. AI can do some wonderful things, but sometimes it can over-enhance images of different eras.

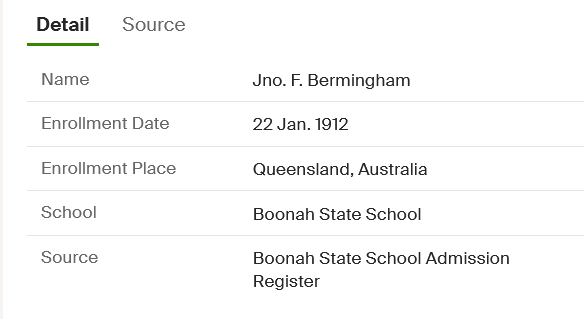

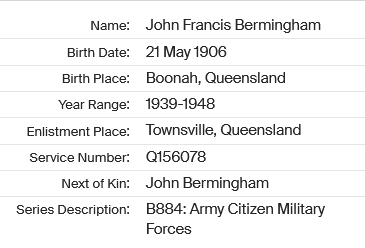

The second child of Ned and Catherine Bermingham’s family was my Dad, John Francis Bermingham, born 21st May 1906. The family were living in Dugandan, just south of Boonah. My Dad, Jack, as he was always known, went to school at Boonah State School and later at the Boonah Rural school. For some reason, the family sent him off to St Joseph’s College at Nudgee in Brisbane in between his schooling at Boonah. Perhaps a need for some good old fashioned brutal Catholic intervention by the Priests & Brothers at Nudgee. Dad was never impressed with his stint at St Josephs College at Nudgee. Jack was also an accomplished woodworker, adept at making tables, chairs, workbenches etc, which I guess, his father Edward would have passed onto him. I still have some items he made in my possession.

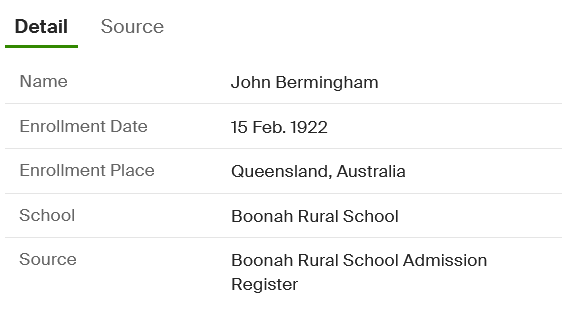

Leaving school in 1923, at age 17, Jack started work immediately with what was then known as the Postmaster Generals Department. He worked at the Boonah Post Office sweeping floors, but soon after trained to become a telephone linesman. Jack was travelling & installing phone lines right across South Western Queensland. The PMG much later became Telecom, and later again, Telstra. The PMG was the Federal Government run institution that was in charge of the postal service, and also what was becoming the national telephone and telegraph network. The telephone network was still in its infancy at that stage. He was sent to work across practically all of regional Queensland. He initially worked installing phone lines out into South Western Queensland, and then up into the Central Queensland and later again into the Northern parts of the state.

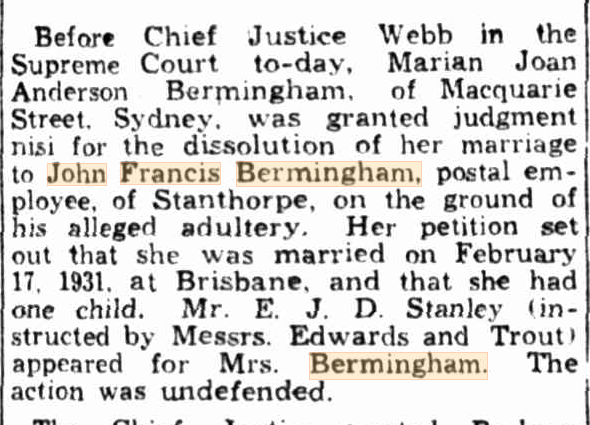

In early 1931, Jack married Marion Joan Anderson McGill at St Stephens Cathedral in Brisbane, the same church his grandparents, Peter and Ellen Bermingham were married in 54 years earlier. Later that year, they had a son, John Francis Leslie Bermingham, born at Goondiwindi in western Queensland. Sadly, the marriage didn’t last, with Joan disappearing & leaving Jack with his young son shortly after. As his mother had disappeared off the scene, young John was raised by his Aunties and Grandparents in the Fassifern Valley, while Jack was away working across the state.

With the breakdown of the marriage & subsequent divorce, Jack was kicked out of the Catholic Church. I’m not certain if Jack had ever held any strong religous beliefs, but I know that he was deeply offended by the excommunication from the church (& even some members of his own family), even to the degree, that I don’t think he ever set foot in a Catholic church again.

Jack got a small mention in the St George newspaper after an incident at Thallon, south west Queensland in 1932.

At the time, Queensland was thriving as a major agricultural state, known for its vast crop production and extensive sheep and cattle grazing. Although mining was already well established, the real boom years for the industry were still ahead. Telecommunications played a vital role in supporting both civilian and industrial activity.

When World War II broke out in 1939, the communication network had to be capable of handling military traffic in addition to the everyday phone calls made across Queensland. If Jack had expected life to become less busy—or had entertained thoughts of joining the military—the outbreak of war quickly put an end to those ideas.

From a military standpoint, there existed a defensive plan known as the Brisbane Line, which was to be implemented if Japanese forces reached mainland Australia. The strategy aimed to make Brisbane the northernmost defensive line, from which the rest of the country would be protected against invasion.

To prepare for this, the outback telephone network was secretly reinforced with backup systems to ensure continued operation if the primary network were destroyed. There were also hidden caches of armaments stored in remote areas as an emergency supply. These locations, too, had to remain connected to the telecommunications network at all costs.

In 1939, Jack was drafted into the Army Citizen Military Forces—in conjunction with his PMG telephone linesman training—to help expand and maintain the outback communication systems. The northern communication network had to be kept operational twenty-four hours a day, three hundred sixty-five days a year.

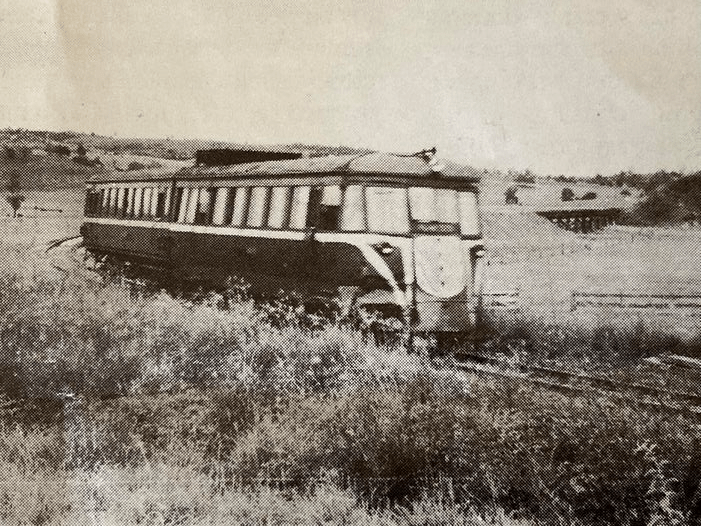

After the end of WW2 in 1945, Jack went straight back to where he was pre-war with the PMG phone network installation across Queensland. But in late 1947, a life-changing event took place, on a trip back to Boonah to catch up with family. He met local lass, Vera Muller, a nurse, who was also on her way home to visit her family in Boonah. The couple met on the Boonah Railmotor.

With Jack’s career in the Army/PMG during WWII, he was part of a large team responsible for keeping the state’s communications network fully operational. Meanwhile, Vera completed her training as a registered nurse at Brisbane General Hospital. Both led very busy lives during the war. When they met, they had plenty to talk about and quickly hit it off. Vera came from a German Methodist family, while Jack’s background was devoutly Irish Catholic—an interesting ethnic mix for the ultra-conservative town of Boonah in 1947. In 1949, Jack Bermingham and Vera Muller were married at the Albert Street Methodist Church in Brisbane.

They immediately boarded a train to North Queensland for a short honeymoon, after which Jack returned to work installing the new automatic telephone exchanges. These unmanned telephone exchanges replaced the old manual switchboards, which had been operated by telephonists who physically connected lines using cords. Each call relied on the operator plugging the cords into the correct slots on a central board that each town or locality had. These were all across the state.

In 1951, Jack was transferred south to carry out similar work throughout South Western Queensland. The constant travel & relocation began to take its toll, and eventually, Vera insisted on a more stable family life. By this stage, my older brother Robert and my sister Jennifer had been born—Robert in Ayr, North Queensland, and Jennifer two years later in Ipswich. I (Geoffrey) arrived in 1954 at the Royal Brisbane Hospital, the same place where Vera had trained as a nurse and obtained her midwifery certificate.

Jack and Vera had purchased a home for the growing family in southside suburban Brisbane. He had also decided prior to that point, on Mums insistance, to a career change. I think they’d both had enough of Jack’s travelling around the state, leaving Mum to raise the children. Jack had worked and lived out of Goondiwindi, Dirranbandi, Mackay, Bowen, Ayr and Townsville. He’d travelled the length and breadth of Queensland, living a nomadic lifestyle while working as a linesman. In 1952, he trained to become a PMG draughtsman, where he was mainly involved in drawing up the plans for the telecommunications and phone network systems that he had previously been involved in installing across the state.

Now based in Brisbane and working in the CBD, the family gained more stability. All of us children attended local schools and eventually lived, studied, and worked around Brisbane. Robert returned to Jack’s old North Queensland stomping grounds for a career in radio broadcasting, which ultimately took him all over Australia. Jen completed a science degree, became a teacher, traveled and worked overseas, then returned to Australia, married, and raised a family in Taree, NSW, before settling back in Brisbane and eventually moving to Warwick on the southern Darling Downs. Geoff pursued a career in machinery sales and equipment hire around South Queensland, based in Brisbane.

Jack’s political leanings were consistently conservative—a preference likely shaped by his rural upbringing—but he remained a moderate Liberal Party voter throughout his life. He came from an era when social conservatism was the norm and admired the post-war Menzies Liberalism that once defined Australia. That said, I believe Jack would have been deeply disappointed by today’s Liberal Party—a disjointed mix of greed and corruption, whose members often seem to run around like headless chooks.

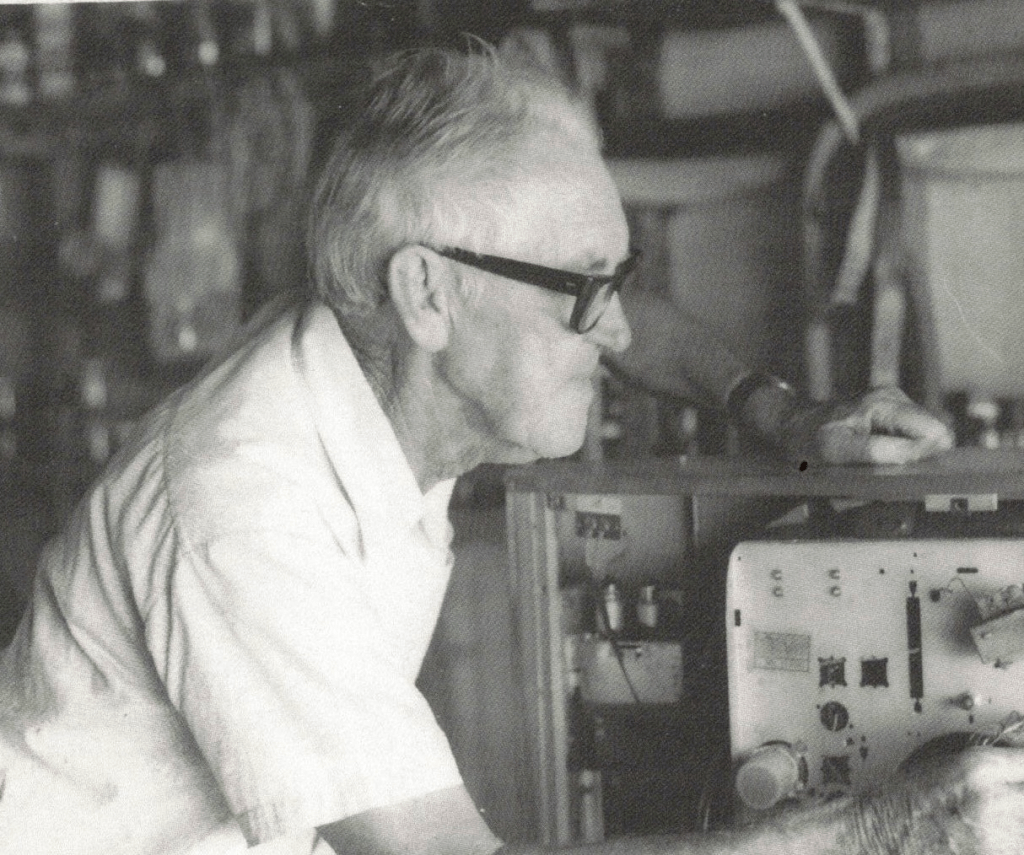

He had a lifelong interest in electronics, which likely stemmed from his career as an electrician and telephone technician. Though he worked long before computers became common, I have no doubt he would have embraced modern technology if he were still around. He would surely have become an IT enthusiast; it would have been right up his alley.

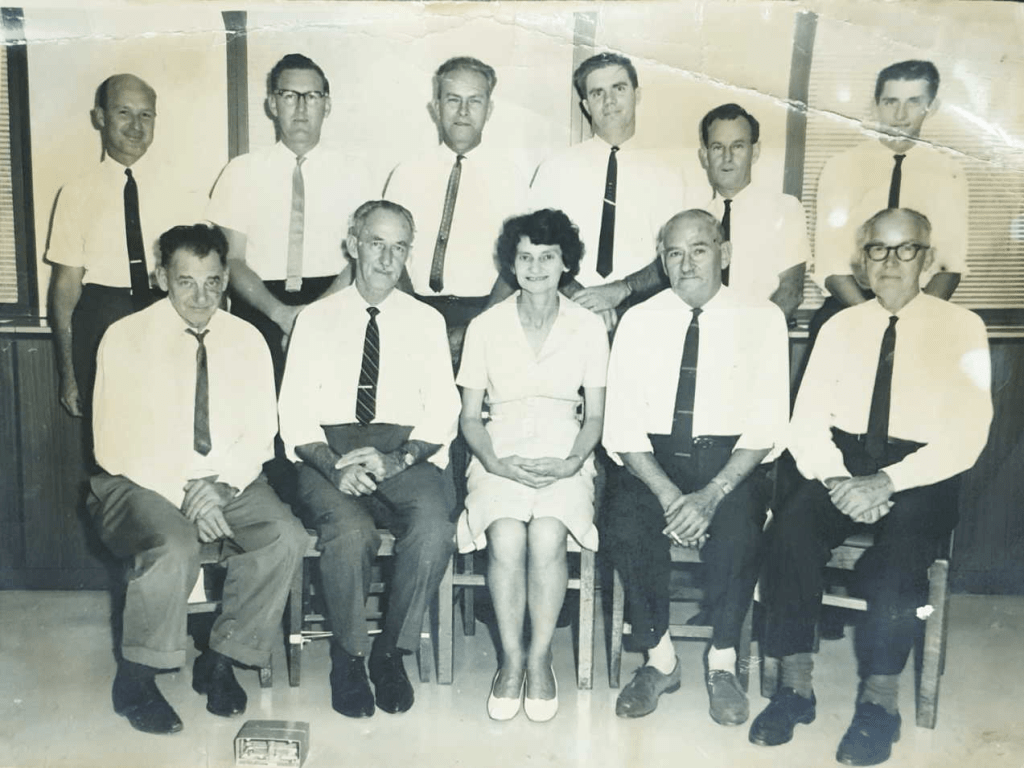

Another of Jack’s favorite pastimes was community service. He served on numerous committees, including the local Rocklea Progress Association, and volunteered at the Brisbane Markets Club, where he was a member. He also introduced the idea of a “buy a brick” fundraiser to help the Salisbury State High School P&C Association build an assembly hall. Although, I suspect the social aspect of these organizations held a strong appeal for him as well. Jack was a member of the Brisbane Irish Club from the early 1950s, shortly after the family moved to Brisbane. Throughout his life, he stayed in close contact with his old PMG colleagues from across the state.

John Francis Bermingham retired in 1971 after working his entire career for one employer. Sadly, the family home was completely submerged in the devastating Brisbane flood of 1974. Dad never fully recovered from the stress of the massive cleanup that followed. I believe this experience initially triggered and accelerated the onset of Alzheimer’s, which ultimately claimed his life.

John Francis Bermingham died on October 8, 1984, at the age of 78. Both Jack and Vera have memorial headstones in the family plot at Boonah Cemetery.